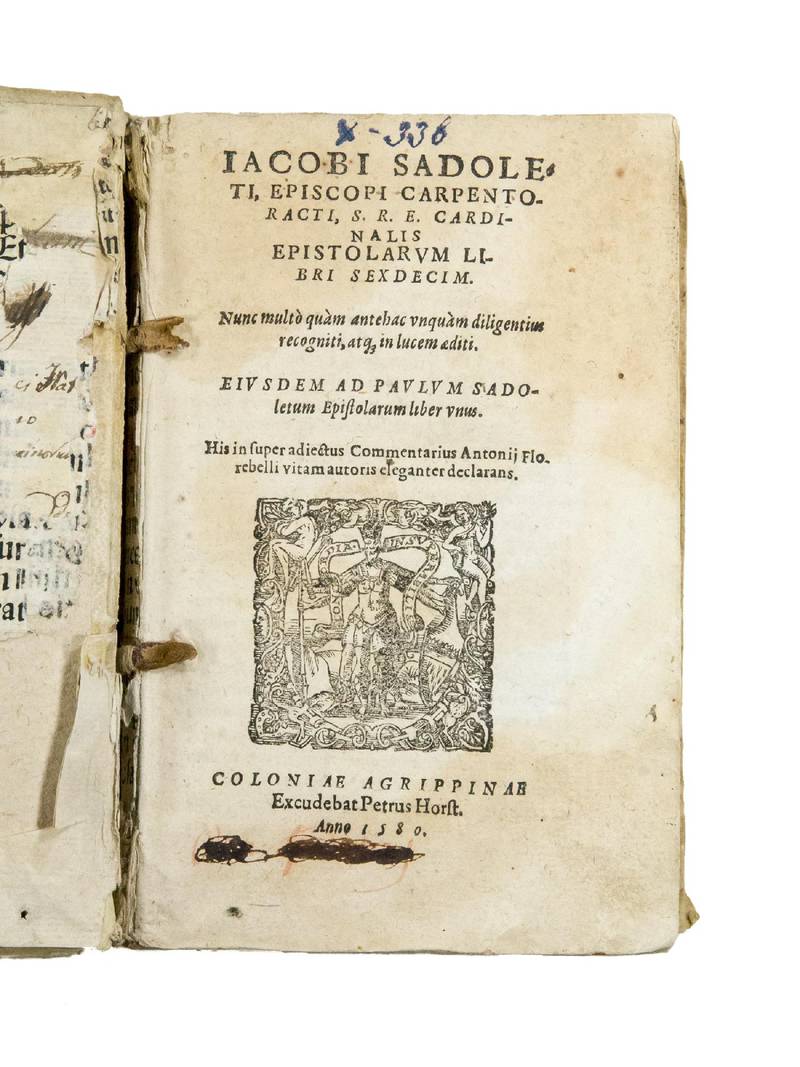

Epistolarum libri sexdecim. Nunc multò quàm antehac unquàm diligentiam recogniti, atq(u)e in lucem editi. Eiusdem ad Paulum Sadoletum Epistolarum liber unus. His insuper adiectus Commentarius Antonij Floribelli vitam autoris eleganter declarans

Autore: SADOLETO, Jacopo (1477-1547)

Tipografo: Peter Horst

Dati tipografici: Köln, 1580

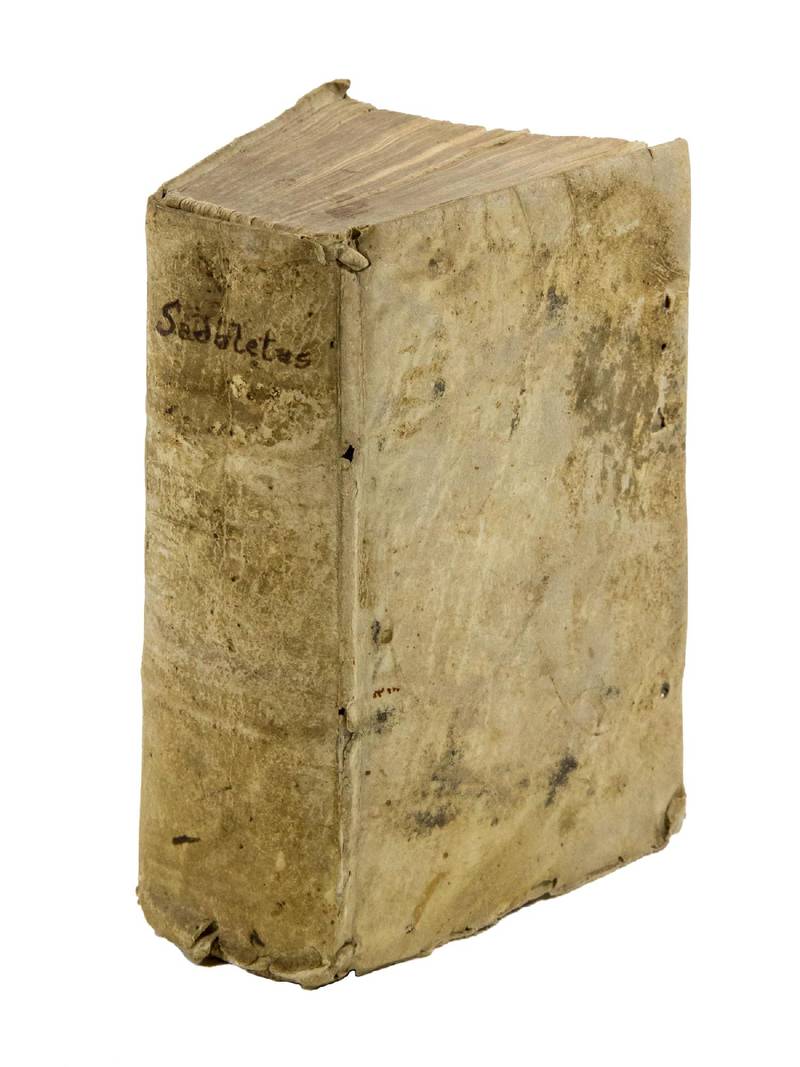

8vo. (8), 743 pp. *8, A-Z8, Aa-Zz8, Aaa4. With the printer's device on the title-page. Contemporary limp vellum.

VD 16, S-1261.

FOUR YEARS after their first publication at Lyon in 1550, Sadoleto's letters were already reprinted in Germany (Cologne), where his epistolary had the greatest diffusion with ten editions until the end of the century (1554 - 3 editions, 1564 - 2 editions, 1567, 1572, 1575, 1580, and 1590). In the present Cologne edition the prefatory letter by Paolo Sadoleto and the Index are retained, as well as Sadoleto's biography by Antonio Fiordibello (here printed immediately after Paolo's letter). The remaining of the volume is a literal reprint of the first edition.

Jacopo Sadoleto was born in Modena, the son of a noted jurist. He studied Latin and Greek letters at the University of Ferrara, where his father was a professor of law. Just before the turn of the century he left Ferrara for Rome, and there obtained the patronage of the learned Cardinal Oliviero Carafa, through whose agency he obtained in 1506 a canonry at San Lorenzo in Damaso.

In the same year he wrote a poem on the newly unearthed Laocoön statue. Following Carafa's death in 1511, he briefly enjoyed the patronage of Federico Fregoso, but course of his career in Rome was set in 1513, when he and Pietro Bembo were appointed to the Apostolic Secretariat by Leo X. To the several benefices, canonries, and pensions he received, the pope added the diocese of Carpentras, in the papal state of Venaissin in Southern France, in 1517. Following the death of Leo X in 1521 Sadoleto went briefly to Charpentras before being recalled by Clement VII to resume his position as domestic secretary, finding himself participant in the confusion and disastrous diplomacy of the Medici court. He returned to Carpentras in May 1527, two weeks before the Sack of Rome.

During his nine-year-stay there he produced, among others, the pedagogical treatise De pueris instituendis (1530), his most frequently published book, and In Pauli epistolam ad Romanos commentariorum libri (1535), his most controversial work, a Pelagianizing commentary on justification that alarmed Erasmus (whose cautions went unheeded), and that was disapproved by the Faculty of Theology of Paris, and was later placed under the ban in Rome.

He was summoned to Rome again 1536 by Paul III, to serve on Gasparo Contarini's commission on ecclesiastical reform. He arrived there on November 1, and soon emerged as a radical critic on the commission when his Consilium de emendanda ecclesia was presented to the pope. While strongly supporting the convocation of the council, Sadoleto undertook his own efforts at conciliation with the Protestants, hoping, like Erasmus, to promote rapprochement through moderates on both sides. But his conciliatory letters to Melanchthon and others had only the effect of enraging the hard-core Catholic conservatives in Germany. His ambitious Epistola ad senatum populumque Genevensem (1539), an appeal for preserving the unity of the historical church, not only provoked a brilliant response from Calvin but opened up serious differences between him and Contarini.

In 1542 Sadoleto was recalled to Rome to work for the council, now to be held at Trent, which opened at the end of 1545. He was assigned to the special commission on conciliar affairs. From his votes it seems clear that no other member was less partisan, less attached to national interest, or more independent of the pope's dynastic ambitions than the bishop of Carpentras. Sadoleto died at the age of seventy and was buried in San Pietro in Vincoli. His remains were transferred in 1646 to the cathedral of Charpentras, which he had helped to build (cf. S. Ritter, Sadoleto. Un umanista teologo, Roma, 1912, passim; and R. M. Douglas, op. cit., passim).

[9023]