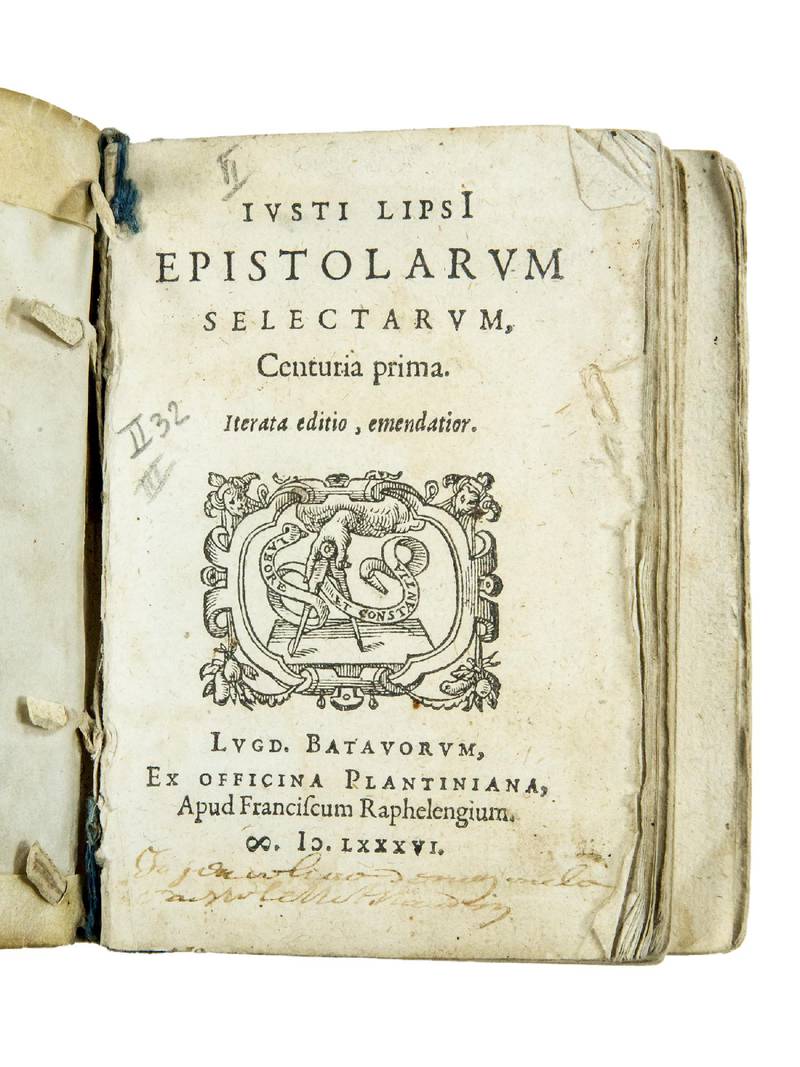

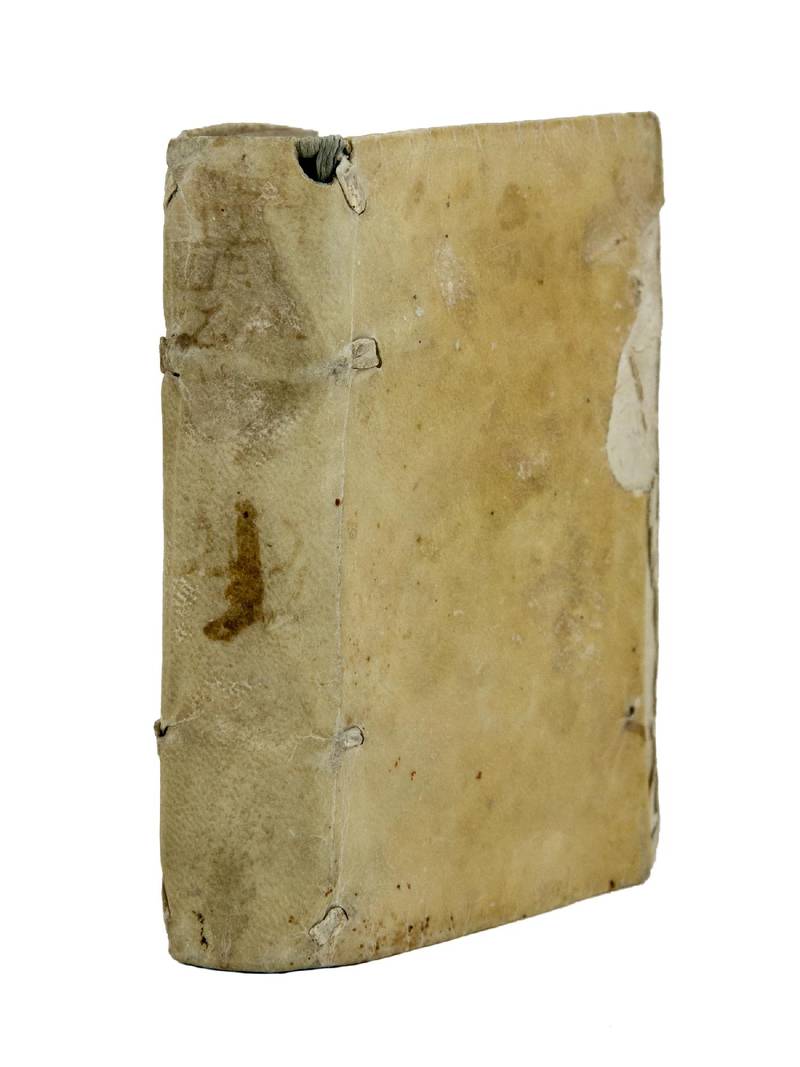

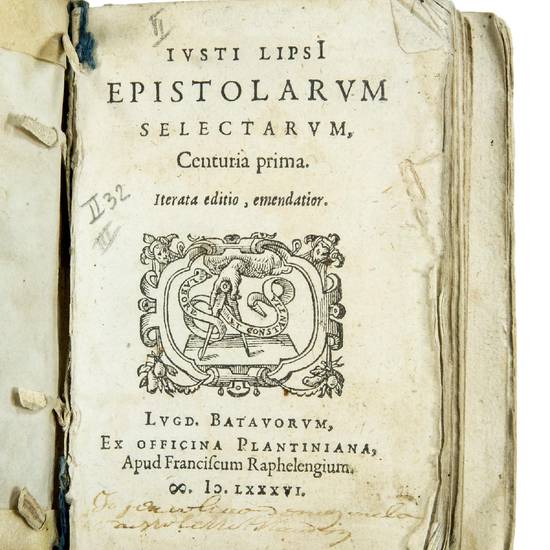

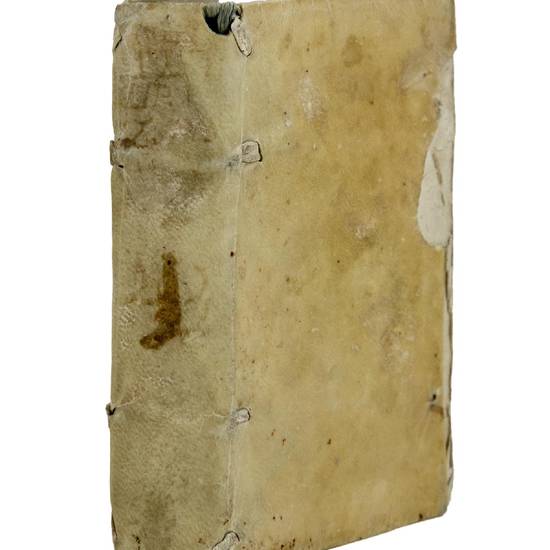

Small 8vo. (16), 377, (4) pp. A-Z8, a8 (-a8, a blank). With the printer's device on the title-page. Contemporary vellum over boards.

Adams, L-815; Bibliotheca Belgica, III, p. 933; Voet, no. 1544.

SECOND EDITION (there are also extant copies with Antwerp as printing place) dedicated to the magistrates of the city of Utrecht (Leiden, November 13, 1585).

This is one of the very first books printed by Frans van Ravelingen (1539 -1597), Christopher Plantin's son-in-law, who managed the Plantin office in Leiden. He also held the chair in Hebrew at Leiden from 1587, and had knowledge of Arabic and Persian. He wrote an Arabic-Latin lexicon, which was published posthumously in 1613. This was said to be the first proper dictionary of the Arabic language. He collaborated on the Antwerp Polyglott Bible, and became the official printer to the University of Leiden. His scholarly printing qualities were one of the attractions that drew Joseph Justus Scaliger to Leiden in 1593.

The present edition contains the same one-hundred letters of the edition princeps (Voet 1543), but has the two laudatory poems by Frans van Ravelingen and by Theodor Esych printed at the end. Added is the imperial privilege of February 21, 1565 granting Christoph Plantin the exclusive rights on the book within the borders of the empire. Although the edition is announced to have been ‘amended', these emendationes have only been very slight (cf. J. de Landtsheer, Justus Lipsius, 1547-1606, and the Edition of his ‘Centuriae miscellaneae, 1586-1605; some Particularities and Practical Problems, in: “Lias”, 25, 1998, p. 75).

Born near Louvain in the town of Overlise, Justus Lipsius distinguished himself as a student of the classics first at the Jesuit college at Cologne and subsequently at the university in Louvain. Shortly after completing his studies, he published a precocious volume of Variae Lectiones (1569), a collection of philological observations on classical texts. Written in a polished Ciceronian style and dedicated to no less a figure than Cardinal Granvelle, chief minister of Philip II in the Low Countries, the volume quickly captured the attention not only of the powerful prelate but also of Europe's scholars.

This initial work had significant and lasting effects on Lipsius' career; the most immediate was his appointment as Latin secretary to Granvelle, who took the young man to Rome, where he was introduced to international power politics as well as to the treasures of Italian libraries, including the Vatican's. An equally significant result of the cardinal's patronage was the opportunity it afforded Lipsius to make the acquaintance of Marc-Antoine Muret, the French scholar who was perhaps the most famous Latinist of his age.

A recent convert to the anti-Ciceronian movement, Muret in turn made a convert of Lipsius. The first fruit of this interest was Lipsius' famous edition of Tacitus (1575), and its culmination was Politicorum libri sex (1589), a compilation of classical political wisdom directed explicitly at the social and religious crises of the sixteenth century. These works won him a reputation as a ‘politician', or student of prudentia, which was never equaled or corrected, at least in Italy, by the fame of his later works.

A corollary interest was the style and philosophy of Seneca. Lipsius' most famous and influential work, De constantia (1584), is a synthesis of Christianity and Stoic philosophy. The crowning achievement of his career are two studies of Stoicism, Manuductio ad stoicam philosophiam and its sequel Physiologia stoicorum (both 1604), and his monumental edition of Seneca (1605).

After two years in the service of the cardinal, Lipsius returned briefly to Leuven, only to leave again in 1571, apparently fearing the strife that had broken out anew between his countrymen and their Spanish rulers. He went to the Viennese court of Maximilian II, where he met such renowned literary figures as Ogier Busbecq, Joannes Sambucus, Joannes Crato, and Stephanus Pighius, who urged that he stay in Vienna. He was unable to find the kind of patronage for which he had hoped, however, and he moved on to Bohemia, Meissen, and Thuringia. While in Thuringia, news of continued turmoil in Brabant deterred his return home, so he secured a recommendation from the Protestant scholar Joachim Camerarius, whom he had met in Leipzig, and this led to an invitation from the Duke of Saxe-Weimar to serve as professor of history at the Lutheran University of Jena in 1572.

Popular among students, Lipsius aroused the jealousy of elder colleagues and the suspicion of Protestant authorities. In March 1574, he left Jena for Cologne and evidently made his peace with the Church. It was in Cologne that he wrote five books of Antiquae lectiones, which are almost exclusively concerned with an enthusiastic examination of Plautus. After a few months, Lipsius returned to Leuven, and in 1576 he proceeded to the degree of doctor of laws, an undertaking that has been ascribed to his association with Muret and an interest in jurisprudence derived from Tacitus. In addition to resuming his work on Tacitus during this brief residence in his homeland, he also published his important Quaestiones epistolicae (1575).

But Lipsius was not yet to find peace. In 1578, with the news of the victory of Don Juan of Austria at Gembloux, he again became apprehensive at the prospect of an invasion by Spanish troops. He fled Louvain, and Spanish soldiers did indeed ransack his deserted house, confiscating and destroying his books and papers. He took brief refuge in the Antwerp home of his friend and publisher, Christopher Plantin. Then, in 1579, he accepted the temporary position of professor of history and law at the Leiden University.

Notwithstanding its explicitly Calvinist make-up, Leiden was a remarkably open university in the beginning, and in Holland Lipsius found a haven from his home province for nearly thirteen years. While there he published his Electa (1580); his Satyra Menippaea: Somnium (1581); his Saturnalia (1582); his De Amphitheatro (1584); his De Amphitheatris quae extra Romam (1584); notes on Valerius Maximus, Seneca, and Velleius Paterculus; and his De recta pronuciatione Latinae Linguae (1586); as well as the major works on constancy and politics. It was there, also, that he delivered the lectures on letter-writing that later became Epistolica institutio of 1591.

By 1591, however, the atmosphere, if not the statutes, of Leiden had become more stridently Calvinist, and Lipsius returned to the southern provinces of the Low Countries, where he was again reconciled to the Catholic Church, largely through the good offices of his boyhood masters, the Jesuits, and he accepted the post of professor of Latin at Leuven. He remained in Leuven for the rest of his days, resisting numerous appeals from foreign courts and especially from Italian churchmen (cf. M. Laureys, ed., The World of Justus Lipsius: A Contribution Towards his Intellectual Biography: Proceedings of a colloquium held under the auspices of the Belgian Historical Institute in Rome, Rome, 22-24 May 1997, Bruxelles, 1998, passim; and H.D.L. Vervliet, Lipsius' jeugd, 1547-1578: analecta voor een kritische biografie, in: “Mededelingen van de Koninklijke Vlaamsche Academie voor Wetenschappen, Letteren en Schone Kunsten van België, Klasse der Letteren”, 31/7, 1969, pp. 9-12).

[9028]