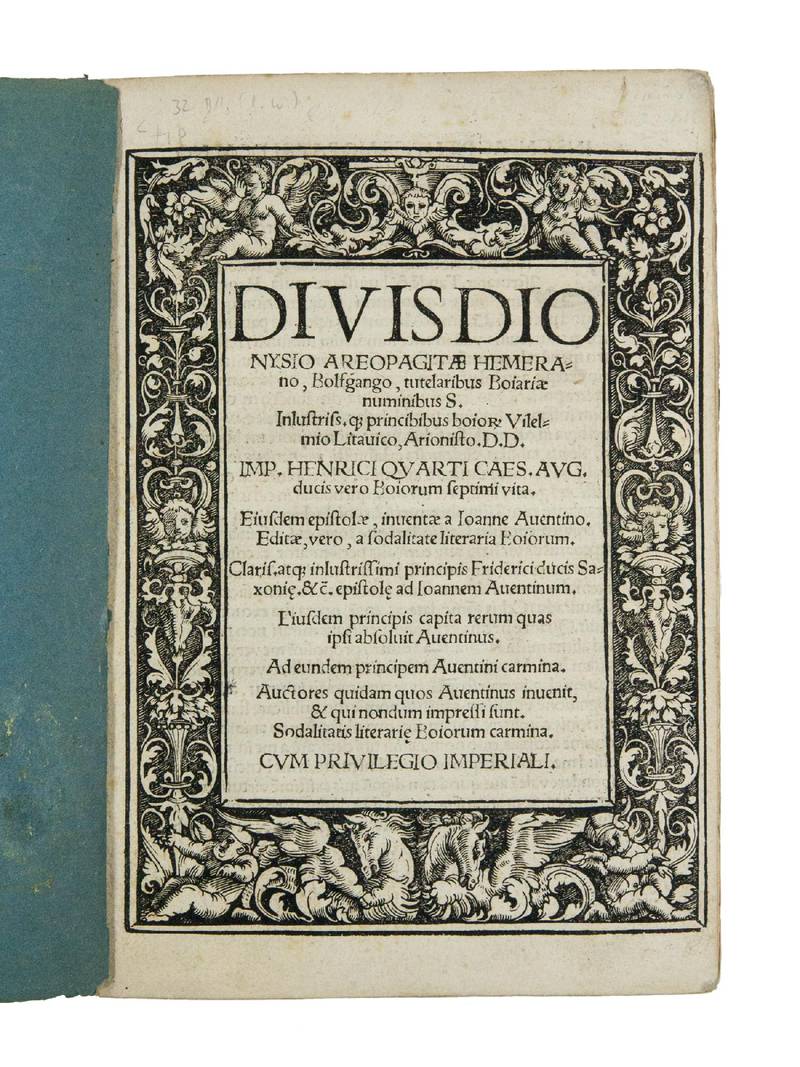

Imp. Henrici Quarti Caes. Aug. ducis vero Boiorum septimii vita. Eiusdem epistolae, inventae a Ioanne Aventino. Editae, vero, a sodalitate literaria Boiorum. Clariss. atq(ue) inlustrissimi principis Fededrici ducis Saxoniae &c. epistolae ad Ioannem Aventinum. Eiusdem principis capita rerum quas ipsi absolvit Aventinus. Ad eiusdem principem Aventini carmina. Auctores quidam quos Aventinus invenit, & qui nondum impressi sunt. Sodalitatis literariae Boirum carmina

Autore: AVENTINUS, Johannes (Thurmair, 1477-1534)

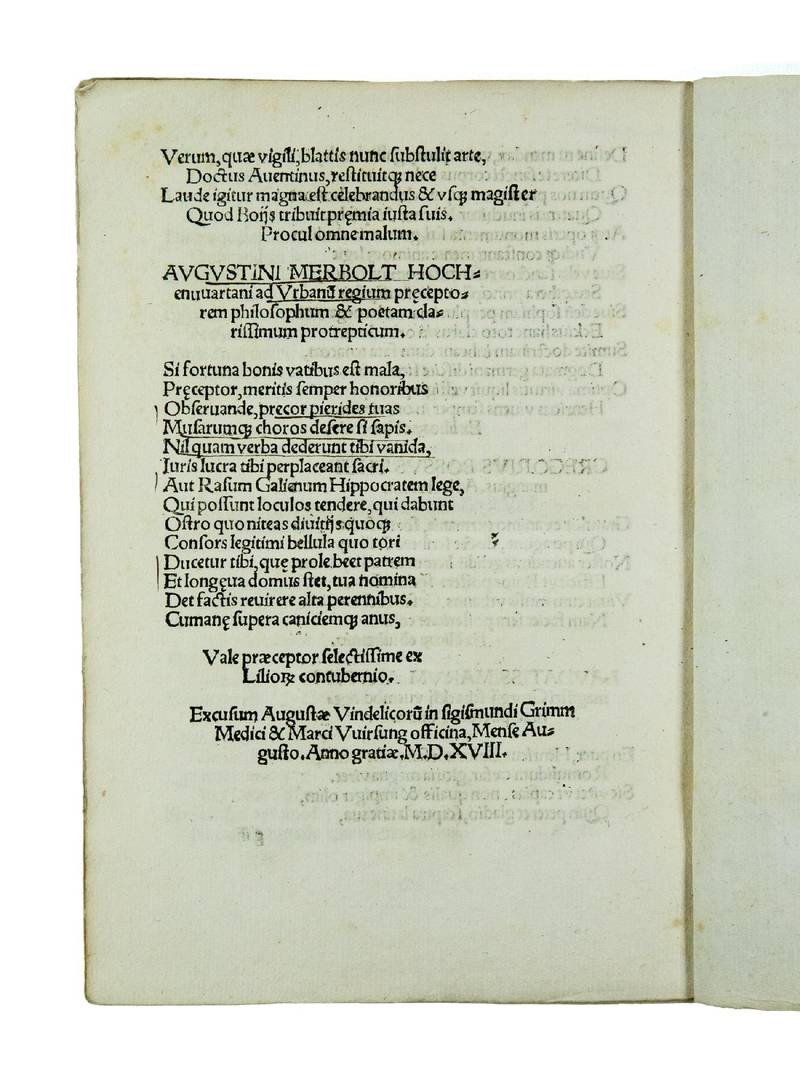

Tipografo: Sigmund Grimm and Marx Wirsung

Dati tipografici: Augsburg, 1518

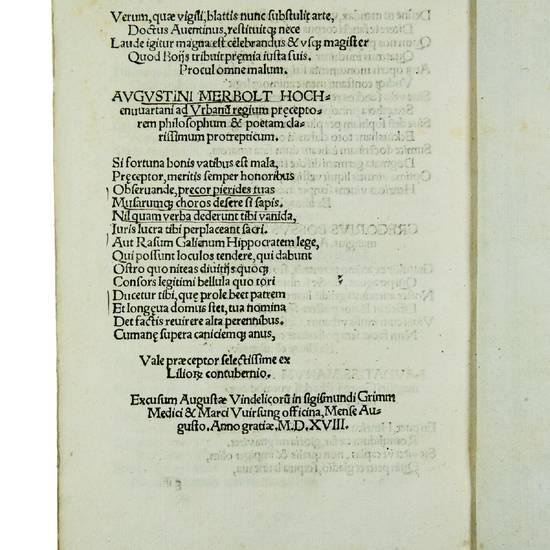

4to. 32 unnumbered leaves (the last is a blank). a6, b-c4, d6, e-g4. Title within an ornamental woodcut border. Wrappers, a fine copy.

VD 16, I-95; J.M. de Bujanda, L'index de l'inquisition espagnole 1583, 1584, (Sherbrooke, 1993), p. 348, no. 737; C. März, Johannes Aventinus, in: “Deutscher Humanismus 1480-1520. Verfasserlexikon”, (Berlin & New York, 2005), I/1, col. 100.

FIRST EDITION. Although Aventinus had contacts with many fellow humanists and noblemen, his extant correspondence with them is surprisingly small. Among a little more than twenty extant letters written by and addressed to him we find among others the names of Konrad Celtis, Urbanus Rhegius, Beatus Rhenanus, Joachim Vadian, Philipp Melanchthon, Conrad Peutinger, and Willibald Pirckheimer.

Aventinus' letters in this volume mostly concern the publication of the life of emperor Henry VI from a codex in the library of the monastery of Saint Emmeram. The first three letters, to the prior of Saint Emmeram, Ambrosius Münzer, to the librarian of the monastery Dionysius Menger and to the priest Ulrich Preu of Pföring, are letters of thanks for their help in the publishing venture. The letter to Leonard von Eck (1480-1550), a powerful figure in the political life of the time and an important councillor to duke William VI of Bavaria, and the two letters by Frederick III the Wise of Saxony to Aventinus are about a project of a chronicle of Saxony and Thuringia the Elector had entrusted to the humanist Georg Spalatin (1484-1545) (cf. Johannes Aventinus, Briefwechsel, in: “Sämmtliche Werke”, S.v. Riezler, ed., München, 1881, I/2, pp. 632-654).

This work also testifies of the short lived Sodalitas literaria Angilostadiensis, an association of men of letters and learning from the environment of the University of Ingolstadt. The society benefited of the patronage of Duke Ernst of Bavaria and was presided by Leonard von Eck. It was licensed by the University (its statutes having been approved by the philosophical faculty), and it drew some local talent into the circle of companionship and scholarly activities. Most members, however, returned to other pursuits when the first flush of enthusiasm had subsided. The organisation languished for a while, then dissolved without formalities. But it was an interesting group while it lasted, and it provided stimulating companions for Aventinus. His first close acquaintance with Leonard von Eck came at this time. Another member, the Greek and Hebrew scholar Matthias Kretz, was destined to play an important part as opponent of Luther. Melchior Seuter was the author of several books on the Turkish wars, which Aventinus read with profit. Urbanus Rhegius lectured on poetry and rhetoric at the University before he was drawn to the side of the reformers and became a preacher in North Germany. A distinguished member was Georg Spies, or Cuspinus, a well-known jurist. There must have been good talk and lively debates, but in Aventinus' eyes the group's essential function was not discussion but publication. However, only the present edition of a medieval life of Emperor Henry IV was published under the auspices of the Sodalitas (cf. G. Strauss, Historian in an Age of Crisis. The Life and Work of Johannes Aventinus, Cambridge, MA, 1963, pp. 67-68).

The present volume opens with the already mentioned biography (attributed to Erlung von Würzburg) of emperor Henry IV (1050-1106), who was chosen German King at Tribur in 1053, crowned at Aix-la-Chapelle in 1054, and appointed duke of Bavaria in 1055, and inherited after his father's death the kingdoms of Germany, Italy and Burgundy. Because of his early age these territories were governed in his name by his mother Agnes. In 1069 Henry took the reins of government into his own hands. No historical incident had more impressed the imagination of the western world than his abasement at Canossa, which represented the king as standing in the courtyard of the castle for three days in the snow, clad as a penitent, and entreating to be admitted to the presence of pope Gregory VII. It was, however, a move of policy to weaken the pope's position at the cost of a personal humiliation to himself. Henry was seen as a friend of the lower orders, was capable of generosity and gratitude, and showed considerable military skill. Unfortunate in the time in which he lived, and in the troubles with which he had to contend, he holds an honourable position in history as a monarch who resisted the excessive pretensions both of the papacy and of the ambitious feudal lords of Germany. Henry's biography is followed by nine of his letters. The volume closes with some Latin poems by the members of the Ingolstadt Sodalitas, i.e. Georg Spies, Johannes Kneissel, Urbanus Rhegius, Otto von Pack, Hieronymus Anfang, Melchior Soiter, Matthias Kretz, Magnus Haldenberger, David Rotmund, Georg Bossus, Georg Schack, and Augustinus Merbolt.

Ambrosius [Münzer of] St. Emmeram (l. a1v)

Dionysius [Menger of] St. Emmeram (l. a2r)

Preu, Ulrich (l. a2r)

From Frederick of Saxony. Torgau, [Sunday before Ash Wednesday] 1514 (l. e3r)

id. Torgau, October 4, 1514 (l. e3v)

Eck, Leonhard von (l. f1v)

Johannes Aventinus was the son of an innkeeper in Abensberg, Lower Bavaria. He attended the local school of the Carmelite monastery and matriculated at the University of Ingolstadt in 1495. In 1496 he received the lower orders and pursued his humanistic studies in Vienna, Cracow and Paris. In 1517 he was appointed tutor to the dukes Louis and Ernest of Bavaria and was named historiographer to the dukes of Bavaria. His Annales Boiorum were severely anticlerical and thus unsuited for publication under the auspices of the Catholic dukes, and the Church set them on the Index. Not until 1554 was an expurgated version of the Annales published at Ingolstadt. Later in his life Aventinus continued to work on a chronicle of all Germany, of which, however, only the first book and an index were completed. He spent the rest of his life in the free imperial city of Regensburg, which remained aloof when the dukes of Bavaria began to repress all Lutheran tendencies. All of Aventinus' works were put on the Venetian Index in 1554 (cf. C. März, op. cit., cols. 72-77).

[9012]