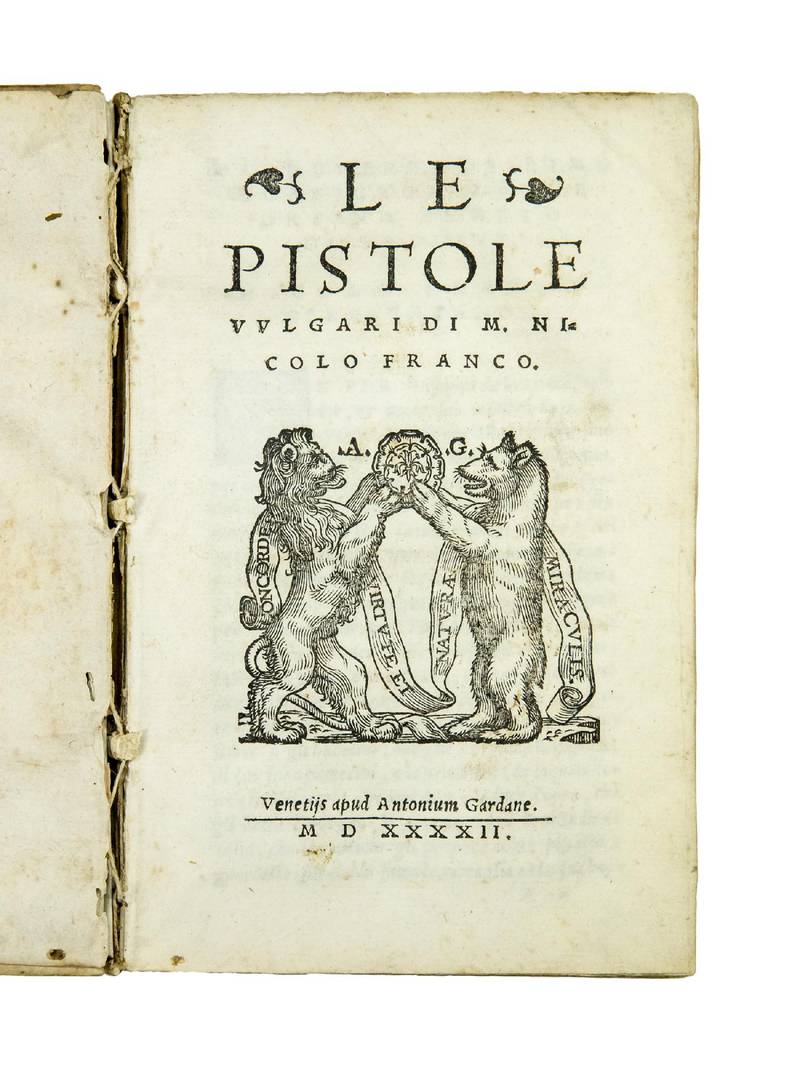

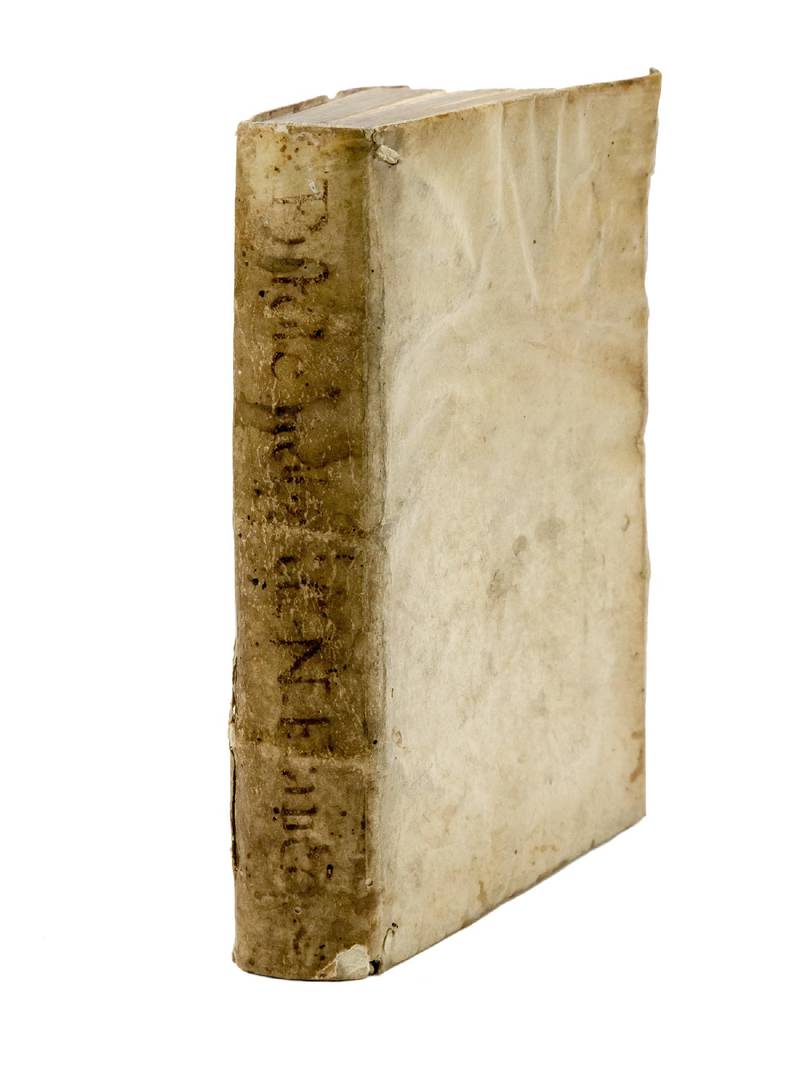

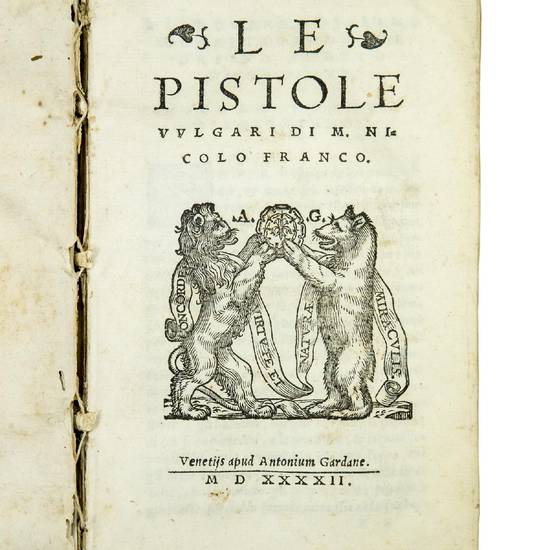

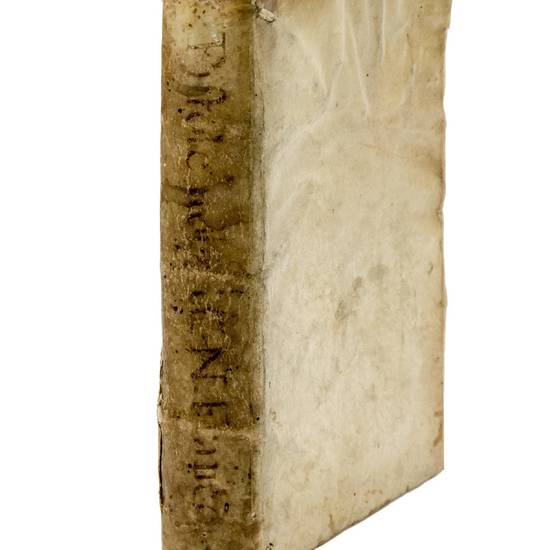

8vo. 267, (1) leaves. A-Z8, AA-KK8, LL4. With the printer's device on title-page and at the end. Contemporary limp vellum, gilt title on the fore-edge.

Adams, F-962; Basso, p. 52; Edit 16, CNCE 19822; Quondam, p. 297; R.L. Bruni, Per una bibliografia delle opere di Nicolò Franco, in: “Studi e problemi di critica testuale”, XV, 1977, p. 84.

THIS SECOND EDITION, in a smaller format, has nearly the same contents as the first, only four letters were omitted and one was added.

The first omitted letter (1st ed., l. 40v), escaped to the attention of F.R. De' Angelis (see infra), is a short one, containing just conventional greetings to a certain Valerio Negroni. The second letter was written to Girolamo Borgia (1st ed., l. 95v), the author of the Historia de bellis italicis, who was one of the favorite targets of the darts that Franco used to throw against pedantry. The third one (1st ed., l. 96v) is a merciless attack on Giovanni Francesco Anisio, a neo-Latin poet close to the Accademia Pontaniana, who was accused to have been a very bad poet and a sodomite. The fourth omitted letter is addressed to Luigi Annichini (1st ed., l. 107v), a highly reputed carver of semi-precious stones, who made works for Pietro Aretino and was praised by Giorgio Vasari. The only added letter is that addressed to Marcantonio Passero, dated Torino, May 3, 1542 (l. 183v).

Besides that, the only other difference between the first and the second edition is that the letter to Bonifacio Pignoli (1st ed. l. 22v) is here addressed to Pompeo Spatafora (2nd ed. l. 50r) (cf. F.R. De' Angelis, Appendice. Per la tradizione a stampa delle lettere di Franco, in: N. Franco, “Le pistole vulgari”, Sala Bolognese, 1986, pp. LV-LXIII).

Nicolò Franco, born of a modest family in Benevento, was first tutored by his brother Vincenzo, a schoolmaster, and later sought his fortune in the literary circles of the nearby Naples. In 1535 he published his first work, a collection of Latin epigrams Hisabella (Naples, Matteo Cancer). One year later he moved to Venice, where through his friendship with the typographer Francesco Marcolini and the poet Quinto Gherardo, he was introduced in the circle of Pietro Aretino. The latter took him as a secretary and entrusted to him the publication of his first book of letters, in which he repeatedly praised the qualities of his new protégé, predicting him a brilliant career. But the characters of the two men were similar to such a degree that they precluded a lasting friendship.

Whatever the reason for the break (probably Franco's intention to publish a book of letters in imitation of that of his master), it came violently in summer of 1538. Thereafter the works of both became a battleground of hostility. Aretino completely suppressed the laudatory remarks on Franco in the later editions of his letters and Franco painted a grotesque portrait of Aretino in the letter A la Invidia (To Jealousy). In mid-1539 he was slashed in the face by one of Aretino's secretaries. When the wound had healed, Franco resolved to leave Venice, where his position had became too risky. In September and October of that year, when the author had already recovered at Casale Monferrato (where he accidentally stopped on his way to France), appeared two of his works destined to have a long-term success: the Dialoghi piacevoli and the dialogue Il Petrarchista, both printed in Venice by Giovanni Giolito.

In Casale, Franco remained for seven years, founding the Accademia degli Argonauti and publishing the Rime contro Pietro Aretino, the Priapea (a collection of satirical and erotic poems which is known only through the third enlarged edition that the author had printed in Basle in 1548), and the Dialogo dove si ragiona delle bellezze. In 1546 he moved to Mantua, where he published the long novel La Philena (1547).

In 1548, after a short stay in Basel, he entered the service of Giovanni Cantelmo, who traveled extensively across the peninsula before settling in Cosenza. Discharged in 1552, and after a brief period in the service of the Prince of Bisignano, Franco tried his luck in Rome in 1555 with the election of Pope Paul IV. In Rome, however, reigned an atmosphere of distrust against him because of the anticlerical invective in his Priapea. Arrested for the first time in 1558 and imprisoned for 8 month, from 1560 to 1568 Franco lived in Rome enjoying a relative calm thanks to the protection of Cardinal Giovanni Morone.

In the years of the pontificate of Pius IV, he wrote a violent pamphlet against the Carafa family, which after the election of the more intransigent Pius V caused him a second arrest in September 1568. The trial ended in February 1570 with a death sentence. Franco was hanged on the bridge of Castel Sant'Angelo on March 11. The death penalty looked disproportionate even to his contemporaries. All his works were prohibited donec expurgentur and put on the Index. The Pistole, like his other works, were republished in expurgated edition in 1604 (Vicenza) and 1615 (Venezia) (cf. C. Simiani, La vita e le opere di Niccolò Franco, Torino, 1894, passim).

Franco played a key role in the birth and development of the Italian epistolography. As a member of Aretino's circle, having a good knowledge of classical languages, he translated many works for his master, among which Erasmus' De conscribendis epistolis (Basle, 1522). In all likelihood, then, it was through the mediation of Franco, a great admirer of the Dutch humanist, that Aretino decided to prepare for printing a collection of his letters (cf. C. Cairns, Nicolò Franco, l'umanesimo meridionale e la nascita dell'epistolografia in volgare, in: “Cultura meridionale e letteratura italiana. I modelli narrativi dell'età moderna, Atti dell'XI Congresso AISLLI, Napoli & Salerno, 14-18 aprile, 1982”, P. Giannantonio, ed., Napoli, 1985, pp. 119-128).

[9071]