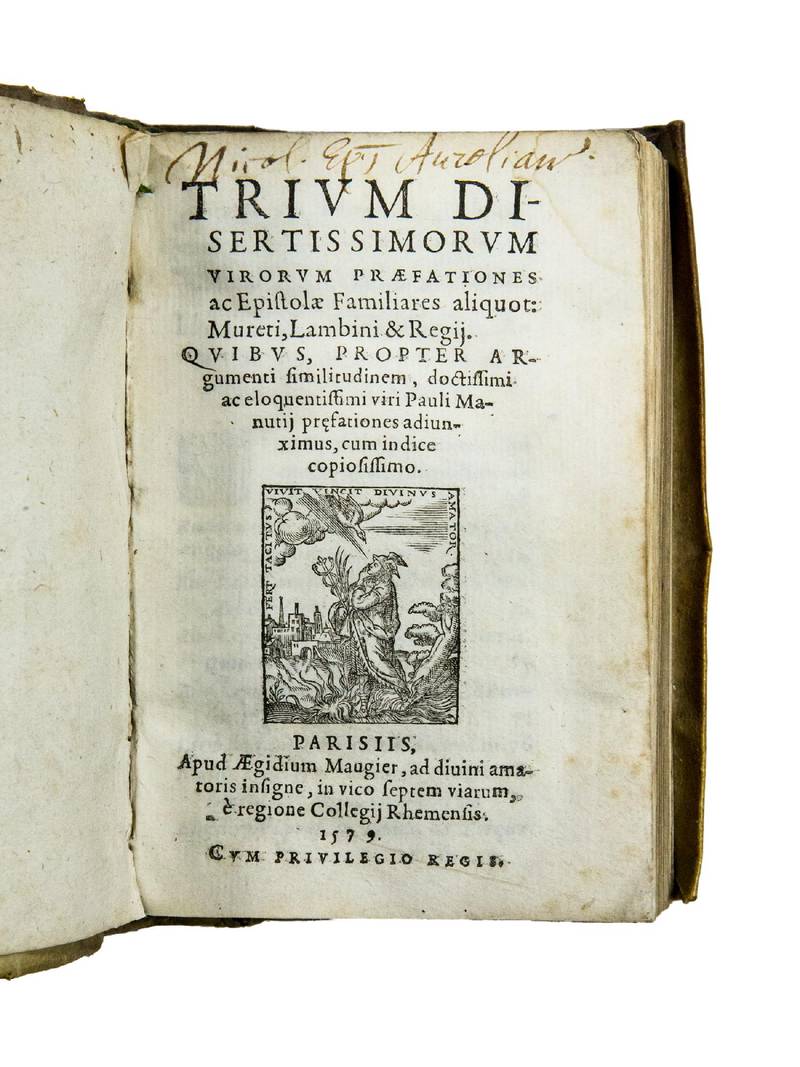

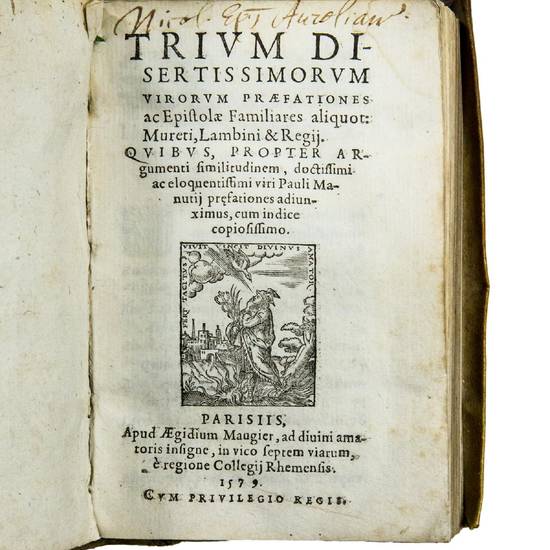

Trium disertissimorum virorum praefationes ac Epistolæ familiares aliquot: Mureti, Lambini & Regij. Quibus, propter argumenti similitudinem, doctissimi viri Pauli Manutij praefationes adiunximus, cum indice copiosissimo

Autore: MURET, Marc-Antoine (1526-1585) - LAMBIN, Denis (ca. 1520-1572) - LE ROY, Louis (ca. 1510-1577)

Tipografo: Gilles Maugier

Dati tipografici: Paris, 1579

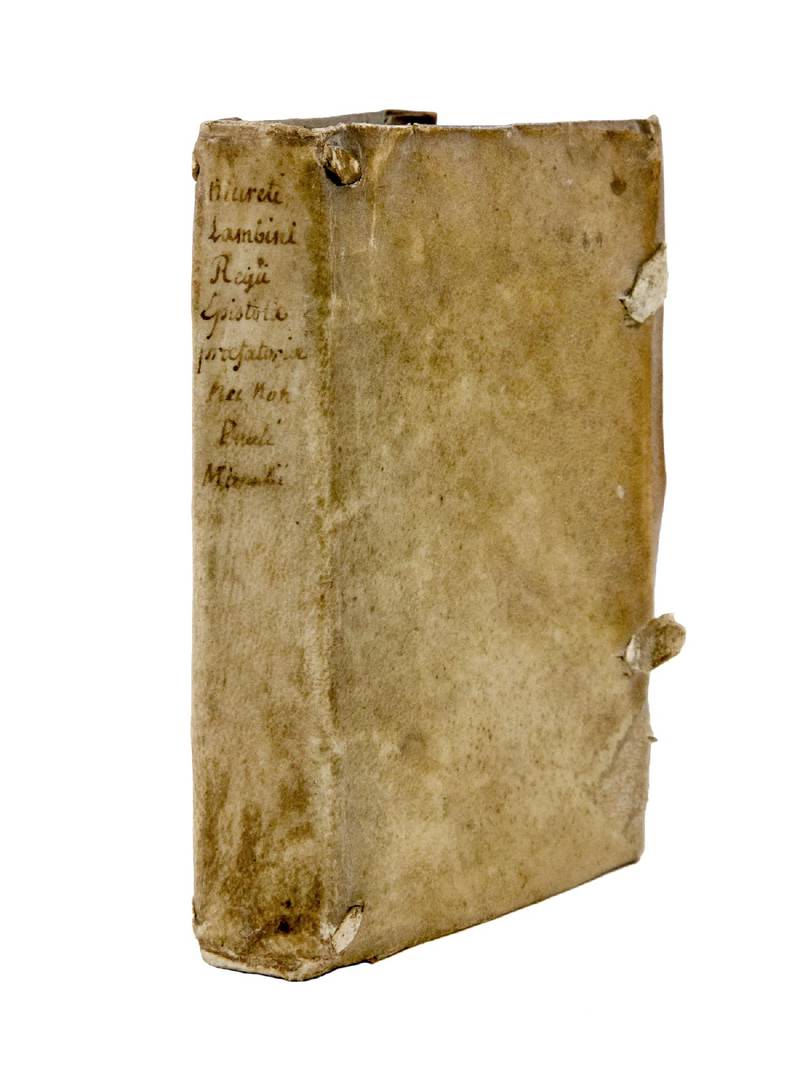

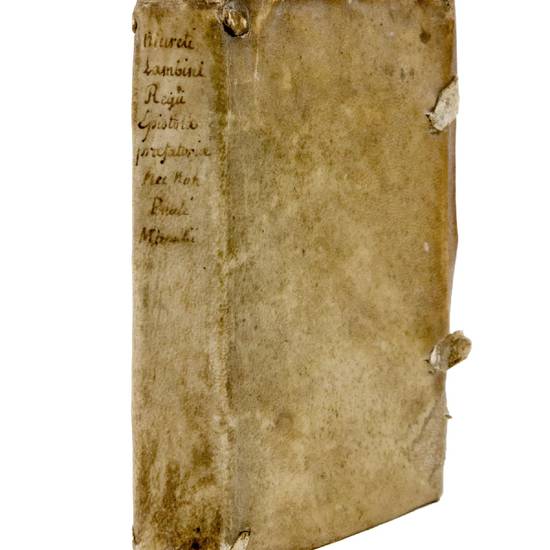

Small 8vo. (26), 3-549, (1), (2 blank) pp. †8, A-Z8, AaMm8 (Mm8 is a blank). With the printer's device on the title-page. Contemporary overlapping vellum, with the bookplate of the Orléans Seminary, gift of D. de Fourcroy, Decanus Aureliensis.

E. Boeuf, La bibliothèque parisienne de Gabriel Naudé en 1630: les lectures d'un libertin érudit, (Genève, 2007), p. 123, no. 225; H. Busson, Le rationalisme dans la litérature française de la Renaissance, 1533-1601, (Paris, 1971), p. 622; W.L. Gundersheimer, The life and works of Louis Le Roy, (Genève, 1966), p. 147, no. XI; E. Pastorello, L'epistolario Manuziano. Inventario cronologico-analitico, 1483-1597, (Firenze, 1957), p. 15, no. 274 (1578 ed.).

SECOND EDITION. The first edition, shared between the printers Gilles Maugier and Jean de Heuqueville, was issued in 1578 in two different formats: in octavo with a separate pagination for Manuzio's Praefationes and in small octavo with the same collation as the present edition, of which are also extant copies with Heuqueville's address.

This collection assembles numerous prefatory and ‘familiar' letters of three great French scholars: Marc-Antoine Muret (1526-1575), Denis Lambin (ca. 1520-1572), and Louis Le Roy (ca. 1510-1577). Some of the Muret-Lambin correspondence had already been published in the letter collection edited by Giovanni Michele Bruto at Lyon in 1561. The letters by Le Roy were first printed at Paris in 1559.

Added are the prefatory letters by Paolo Manuzio (1512-1574), which had already been printed in Venice in 1558

MURET:

SECOND EDITION. In this anthology is printed for the first time a choice of 22 letters (some prefatory) by Muret, which were not included in the volume issued a year later by Muret himself at Paris.

The volume opens with a series of letters that Muret wrote to Denis Lambin in 1558/9. “Cette année là, il [Muret] publie son Horace, ne s'en prenant directement à Muret à aucun moment dans son texte, comme si de rien n'était. Mais en parallèle, il transmet à Giovanni Michele Bruto (1515-1594) onze lettres peu glorieuses que le Limousin lui avait envoyeées à la fin des années 1550. Elles seront publiées en 1561 dans un recueil de correspondances édité par Sébastien Gryphe, a Lyon: Epistolae clarorum virorum, quibus veterum autorum loci complures explicantur, tribus libris a Joanne Michaele Bruto comprehensae: atque nunc primum in lucem editae.Ces documents évoquent les évènements fâcheux qui ont poussé Muret à fuir la France, puis les mauvaises rumeurs qui ont mis à mal ses tractations auprès du cardinal d'Este. Le Limousin était loin de souhaiter leur publication. Voir ses petits ennuis exposés aux yeux de toute la communauté lettrée de l'époque le met dès lors en rage. Lambin s'est bien vengé, deux ans après avoir été lui-même lésé. Et cette fois-ci, il prend a parti toute la Republique des lettres” (M. Roux, Les ‘Variae lectiones' de Marc-Antoine Muret: l'esprit d'un homme, l'esprit d'un siècle, Thesis, Lyon, 2011, p. 216).

from Manuzio, Paolo. [end of 1559] (leaf Aiiiv)

id. [Venezia, August 25?, 1558] (leaf Avr).

Lambin, Denis. Padova, February 4, 1558 (p. 3)

id. Padova, February 4, 1558 (p. 5)

from id. Corneliano, February 20, [1558] (p. 6)

id. Padova, February 23, [1558] (p.11)

id. Padova, February 25, [1558] (p. 13)

id. Padova, February 29, [1558] (p. 15)

id. Padova, March 15, [1558] (p. 17)

id. Padova, April 13, [1558] (p. 18)

id. Padova, July, [1558] (p. 19)

id. Treviso, November 28, [1558] (p. 20)

from id. Corneliano, August 12, 1558 (p. 22)

id. Padova, August 27, [1558] (p. 26)

from id. August 18, [1558] (p. 27)

id. Ferrara, July 17, 1559 (p. 31)

from id. Lucca, August 1, 1559 (p. 34)

Brinon, Jean de. Paris, November 24, 1552 (p. 48)

Gonzaga, Scipione. Rome, May 1, 1571 (p. 54)

Este, Ippolito d'. [1559] (p. 58)

Suriano, Jacopo. [1555] (p. 65)

Avanson, Jean de. Venezia, October 1, 1555 (p. 71)

Studiosis. [1554] (p. 76)

Loredan, Bernardino. Venezia, October 15, 1554 (p. 77)

Bembo, Torquato. Padova, May 7, 1558 (p. 84)

Gonzaga, Francesco. Padova, August 1, 1558 (p. 87)

Turnèbe, Adrien. Paris, March 15, 1562 (p. 92)

Marc-Antoine Muret exemplifies the essence of French Renaissance humanism. A master of Latin and student of Classical antiquity, he not only engaged in the recovery and exposition of ancient texts, but also actively employed the old genres and skills in the contemporary ecclesiastical and public spheres. He wrote Latin poetry, both sacred and profane, delivered public orations in Latin, and lectured in various schools throughout France and Italy on authors as diverse as Catullus and Tacitus and on topics as varied as Greek philosophy and Roman law. His list of friends, acquaintances, teachers, and students reads like a Who's Who of the period.

Born near Limoges, he attracted soon the notice of the elder Scaliger and was invited to lecture in the archiepiscopal college at Auch. He afterwards taught Latin in the Collège de Guyenne at Bordeaux, where he had Montaigne among his pupils and where his Latin tragedy Julius Caesar was presented. Some time before 1552 he delivered a course of lectures in the College of Cardinal Lemoine at Paris, which drew a large audience, King Henry II and his queen being among his hearers. He twice received counsel from the elder Scaliger at Agen and at Poitiers participated in a poetry contest judged by Jean Salmon Macrin. At Limoges, he knew Jean Dorat and Joachim du Bellay. Pierre Ronsard attended his lectures at various times, and the latter corresponded with him throughout his life. Denys Lambin, the great commentator of Lucretius, befriended him until their odd falling out in 1559. At Paris, he crossed paths with George Buchanan, Claude Goudimel, François le Duchat, Étienne Jodelle, and other well-known poets, printers, musicians, and intellectuals active there.

His success made him many enemies, and he was thrown into prison on a charge of homosexuality and heresy, but released by the intervention of powerful friends. The same accusation was brought against him at Toulouse, and he only saved his life by timely flight. The records of the town show that he was burned in effigy as a Huguenot and as sodomite (1554). This led to his flight to Italy.

He held a professorship of humanities at Venice, where he became a friend of Paolo Manuzio. Then accepted an invitation of cardinal Ippolito d'Este to settle in Rome, where he lectured for more than twenty years under no small difficulties and restrictions, foreseeing the decline of learning in Italy and making every effort to arrest it. In 1561 Muret revisited France as a member of the cardinal's suite at the conference between Roman Catholics and Protestants held at Poissy. He returned to Rome in 1563.

His lectures gained him a European reputation, and in 1578 he received a tempting offer (which he declined) from the king of Poland to become teacher of jurisprudence in his new college at Kraków. Despite the scandal and turbulences, he received the holy orders in 1576 and was induced by the liberality of Gregory XIII to remain in Rome, where he died in 1585 (cf. V. Leroux, Introduction, in: M.-A., Muret, “Juvenilia”, Genève, 2009, pp. 13-24; see also Ch. De Job, Marc-Antoine Muret: Un professeur Français en Italie dans la secondemoitié du XVIe siècle, Paris, 1881, passim, F. Delage, Marc-Antoine Muret, poète français, Limoges, 1910, passim; D. Menager, Marc-Antoine Muret à la recherche d'une patrie, in: “La circulation des hommes et des oeuvres entre la France et l'Italie à l'époque de la Renaissance”, A. Fontana, ed., Paris, 1992, p. 260-269; and R. Trinquet, Un maître de Montaigne: l'humaniste limousin Marc-Antoine Muret, in: “Bulletin de la Société des amis de Montaigne”, 1966, pp. 3-17).

Muret's library passed to the Jesuits in Rome, and from there in great part to the Library of king Victor-Emmanuel (today Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, Rome) (cf. P. Renzi, I libri del mestiere: ‘La Bibliotheca Mureti' del Collegio Romano, Siena, 1993, passim).

LAMBIN:

FIRST EDITION of this collection of Lambin's prefatory letters. Some of his correspondence, especially several letters exchanged with Marc-Antoine Muret, had been published in the anthology Epistolae clarorum virorum (Lyon, 1561) by Giovanni Michele Bruto (cf. L.C. Stevens, Denis Lambin: Humanist, Courtier, Philologist, and ‘Lecteur Royal', in: “Studies in the Renaissance”, IX, New York, 1962, pp. 236-237; see also H. Potez, Deux années de la Renaissance d'après une correspondance inédite [of Lambin], in: “Revue d'histoire littéraire de La France”, XIII,1906, pp. 458, 658).

Muret, Marc-Antoine. Corneliano, February 20, [1550] (p. 9)

id. Corneliano, August 12, 1558 (p. 22)

id. [Corneliano?], August 18, [1558?] (p. 27)

id. Lucca, August 1, 1559 (p. 34)

Des Mesmes, Henri. Paris, November 19, 1584 (p. 97)

Monvilliers, Jean de. Paris, April 3, [1568] (p. 98)

Du Mesnil, Baptiste. Paris, October 16, n.y. (p. 101)

Angoulème, Henri d'. Paris, October 19, [1566] (p. 105)

Hurault de Cheverny, Philippe. Paris, January 30, 1572 (p. 113)

Tournon, Louis de. Paris, April 11, n.y. (p. 117)

Charles IX. Lyon, April 15, 1561 (p. 123)

Tournon, François de. Venezia, April 15, 1558 (p. 140)

Des Mesmes, Henri. Paris, 1566 (p. 148)

Erudito & humanitate polito Lectori. [Paris], February 13, 1566 (p. 159)

Valois, Henri de. Paris, June 13, 1567 (p. 176)

Angoulème, Henri d'. Paris, July 13, 1567 (p. 204)

Valois, Henri de. Paris, November 20, 1568 (p. 217)

Vaillant de Guélis, Germain. Paris, October 17, 1576 (p. 233)

Charles XI. Paris, November 1, 1563 (p. 236)

Des Mesmes, Henri. Paris, August 1, 1563 (p. 260)

Erudito lectori (p. 264)

Tertiae editionis lectori. Paris, November 8, 1570 (p. 271)

Ronsard, Pierre de. [Paris, 1563?] (p. 289)

Vaillant de Guélis, Germain. [1563?] (p. 291)

Muret, Marc-Antoine. Paris, September 12, 1563 (p. 296).

Turnèbe, Adrien. Paris, October 31, 1563 (p. 300)

Dorat, Jean. Paris, September 30, 1563 (p. 302)

Denis Lambin was of rather humble origin. His father, Nicolas, was a locksmith. He was born at Montreuil-sur-Mer (Picardie). After preliminary studies in his native city, he received the tonsure, and left for Paris at the age of fifteen. He then had the opportunity to study at one of the most famous schools of early Renaissance France, the Collège du Cardinal Lemoine.

In 1547 Lambin entered the services of the Cardinal de Tournon, whom he accompanied on two visits to Italy. In this way he saw Rome, Venice, and Lucca, and was brought into contact with Italian scholars such as Faerno, Muret, Sirleto, Fulvio Orsini, etc. In the Cardinal's entourage, he also had the opportunity of meeting many of the most distinguished poets, jurists, and men of letters of his time. In spite of his close association with a prelate, who was not noted for his mansuetude in regard of heretics, Lambin cultivated the friendship of many Protestants.

After staying for a year or two in Paris, he returned to Italy for five years, mostly spent in Rome (where he had the opportunity of collating many manuscripts in the Vatican and elsewhere), Venice, and Lucca. In 1561 (the year of publication of his Horace) Lambin was appointed as one of the Royal Readers of Latin, but was soon transferred to a readership in Greek. Three years afterward he published his masterly edition of Lucretius. In a commentary upon Aristotle's Politics, he discusses the value of a humanistic education and comes pessimistically to the conclusion, that only wisdom and virtue of an educated man can save him in an illiberal society where the chief amusements are drinking, gluttony, and indulgence in erotic pleasures.

Lambin's works were not only in high esteem in contemporary France, but also acclaimed by humanists in Italy. Paolo Manuzio, in a letter to Lambin, expresses his admiration for his friend's mastery of Latin and Greek, his broad culture and his critical acumen (cf. L.C. Stevens, op.cit., passim). His death (September 1572) is said to have been caused by his apprehension that he might share the same fate of his friend Pierre de la Ramée, who had been killed in the Massacre of St. Bartholomew.

Lambin's work shows a marked advance, and opens a new era in the history of textual critic. He does not, however, indicate with sufficient exactness the manuscripts he consulted. It is evident that for Lucretius he had examined one of the two manuscripts later recognized as fundamental by Lachmann. Moreover, the commentary on Horace and Lucretius is extensive and accurate, contains many quotations, correct remarks, and explanations based on a profound knowledge of Latin. Lambin does not affect the rigorous method of modern philologists. Like older scholars he is often capricious, arbitrary, erratic. Despite these defects, common in his day, Lambin's work retains an important value and is consulted even today (cf. H. Potez, La jeunesse de Denys Lambin, in: “Revue d'histoire littéraire de La France”, IX, 1902, pp. 382-413; XIII, 1906, pp. 458-498; and XXVII, 1920, pp. 214-251 and 409-426).

LEROY:

W.L. Gundersheimer, The Life and Works of Louis Le Roy, Genève, 1966, p. 146, no. XI.

THIS IS A REPRINT of Le Roy's Epistolae selectiores first published at Paris in 1559.

(Lodovici Regii Constantini selectiores aliqot Epistolæ, pp. 307-419:)

Edward VI, King of England. London, January 23, 1551 (p. 307)

Charles of Lorraine. Reims, July, 1547 (p. 311)

Strozzi, Pietro. Paris, June 13, 1558 (p. 314)

Bertrand, Jean. Paris, April 4, 1559 (p. 315)

Du Bellay, Jean. Paris, March 15, 1561 (p. 322)

Armagnac, Georges d'. Rambouillet, March 4, 1547 (p. 323)

Poncher, Etienne. Coutances, June 27, [1551?] (p. 326)

Poyet, Guillaume. Melun, January, 1540 (p. 327)

Chemanus, Franciscus [Montholon, François de?]. Paris, June 1543 (p. 329)

Olivier, François. Chalons sur Marne, May 15, 1552 (p. 331)

Ad curiam Parisiensem (p. 351)

Epistola in scholis Tolosanis (p. 356)

Carle, Lancelot de. Fontainebleau, April 18, n.d. (p. 360)

Bunel, Pierre. Paris, May 1, 1562 (p. 362)

François I. Blois, February 12, 1560 (p. 373)

Philip II, King of Spain. Paris, April 1, 1559 (p. 375)

Edward VI, King of England. London, February 1, 1551 (p. 377)

Savoia, Emanuele Filiberto di & Maguerite de France, Duchess of Berry and Savoy. Paris, April, 1559 (p. 379)

Charles of Lorraine. Blois, December 12, 1560 (p. 380)

François de Lorraine, Duc de Guise. Blois, December 27, 1558 (p. 383)

Olivier, François. Blois, February 3, 1560 (p. 386)

Perrenot de Gravelle, Antoine. Paris, April, 1559 (p. 389)

Monluc, Jean de. Blois (p. 390)

L'Hôpital, Michel de. Chinon, May 9, 1560 (p. 392)

Marillac, Charles de & Morvillier, Jean de. Tours, Easter [April 14], 1560 (p. 394)

Charles of Lorraine. Paris, April 1, 1559 (p. 401)

Philip II, King of Spain. Paris, April 1, 1559 (p. 402)

Medici, Catherine de'. Blois, January 5, 1560 (p. 404)

Bérenger du Guast, Louis de. Paris, October 22, n.y. (p. 405)

Poyet, Guillaume. Paris, January 1, 1541 (p. 408)

In Guliel. Budæi vita Præfatio. [1540] (p. 411)

Bauffremont, Nicolas de. [1575?] (p. 416)

Louis Le Roy (1510-1577), a colleague of the French humanist Du Bellay, was trained in the humanistic curriculum, moved from Paris to Toulouse in 1535 to study law, and returned to the court in 1540 to enjoy the patronage of Guillaume Poyet, Chancellor of France and reformer of the French judicial system under Francis I.

Working in the tradition of Hellenistic French humanism, by 1555, Le Roy had established a strong reputation as a translator. Le Roy's career as a humanist scholar coincided with those of Erasmus, Rabelais, Montaigne, Thomas More, and Juan Luis Vives, and he is versified by Joachim Du Bellay who contributed translations of poetic passages for the commentary of Le Roy's 1559 translation of Plato's Sympose.

What little is known about him is derived from his translations and the Vicissitude. Le Roy's works also bear traces of his travels and receptions at court, including an account of a trip to England in October 1550, where he was received by the child king King Edward VI, and served by William Paget. Following this stay, Le Roy published his translations of Isocrates in 1551.

The De la vicissitude ou variété des choses en l'univers (‘Of the Interchangeable Course, or Variety of Things in the Whole World'), Le Roy's most serious and significant work, was produced late in his life, two years before his death, and achieved great popularity in France and abroad. In this treatise Le Roy celebrates ‘the excellence of this age', his purpose being ‘a comparison of this later age, with all antiquity in Armes, in Learning, and all other Excellency'. To establish his position, Le Roy makes a definitive break with the venerable ancients, distinguishing the modern from the ancient past, and situating his own forward-looking narrative of the progress of civilization against a Providential historiography. Le Roy's primary concern in the treatise is to develop a comparative model for the history of civilization, a model that will apply universally to all civilizations (cf. W.L. Gundersheimer, op. cit., passim).

MANUZIO:

Paolo Manuzio's Praefationes were first published at the end of the volume of his Latin letters at Venice in 1558. In the present edition are reprinted all the Praefationes of the first edition, disposed in the same order, with the only addition of a prefatory letter Ad Antonium Carlonem Allifarum Principem [to Antonio Diaz Garlón, count of Alife] (Venezia, 1535, p. 545), which was first added in the 1560 edition.

Paolo was the youngest son of Aldo Manuzio the Elder. He had the misfortune to lose his father at the age of two. After this event his grandfather and two uncles, the three Asolani, carried on the Aldine Press, while Paolo prosecuted his early studies at Venice. Excessive application hurt his health, which remained weak during the rest of his life. At the age of twenty-one he had acquired a solid reputation for scholarship and learning.

In 1533 Paolo undertook the conduct of his father's business, which has latterly been much neglected by his uncles. Paolo determined to restore the glories of the house, and in 1540 he separated from his uncles. The field of Greek literature having been well night exhausted, he devoted himself principally to the Latin classics. He was a passionate Ciceronian, and perhaps his chief contributions to scholarship are the corrected editions of Cicero's letters and orations, his own epistles in a Ciceronian style, and his Latin version of Demosthenes. Throughout his life he combined the occupations of a scholar and a printer, winning an even higher celebrity in the former field than his father had done. Four treatises from his pen on Roman antiquities deserve to be commemorated for their erudition no less than for the elegance of their Latinity.

Several Italian cities contended for the possession of so rare a man. He also received tempting offers from the Spanish court. Although his publications were highly esteemed, their sale was slow. Thus his life was a permanent struggle with pecuniary difficulties. In 1556 he received for a time external support from the Accademia Veneta, founded by Federico Badoer, who failed disgracefully in 1559, and the academy was extinct in 1562. Meanwhile Paolo had established his brother Antonio, a man of good parts but indifferent conduct, in a printing office and book shop at Bologna. Antonio died in 1559, having been a source of trouble and expense to Paolo during the last four years of his life. Other pecuniary embarrassment arose from a contract for supplying fish to Venice, into which Paolo had somewhat strangely entered with the government.

In 1561 Pius IV invited him to Rome, offering him a yearly stipend of 500 ducats, and undertaking to establish and maintain his press there. The profits were to be divided between Paolo Manuzio and the Apostolic Camera. Paolo accepted the invitation, and spent the larger portion of his life, under three papacies, with various fortunes in the city of Rome. The works published by the Stamperia del Popolo Romano were mostly Latin works of theology and Biblical or patristic literature. Meanwhile his eldest son, the younger Aldo, had succeeded him in the management of the Venetian printing house. Overtaxed with studies and commercial worries Paolo died at Rome in his sixty-second year (cf. T. Sterza, Paolo Manuzio editore a Venezia (1533-1561), in: “ACME. Annali della Facoltà di lettere e filosofia dell'Università degli studi di Milano”, 61/2, 2008, pp. 123-168; and F. Barberi, Paolo Manuzio e la stamperia del popolo romano (1561-1570): con documenti inediti, Roma, 1942, passim).

[9036]