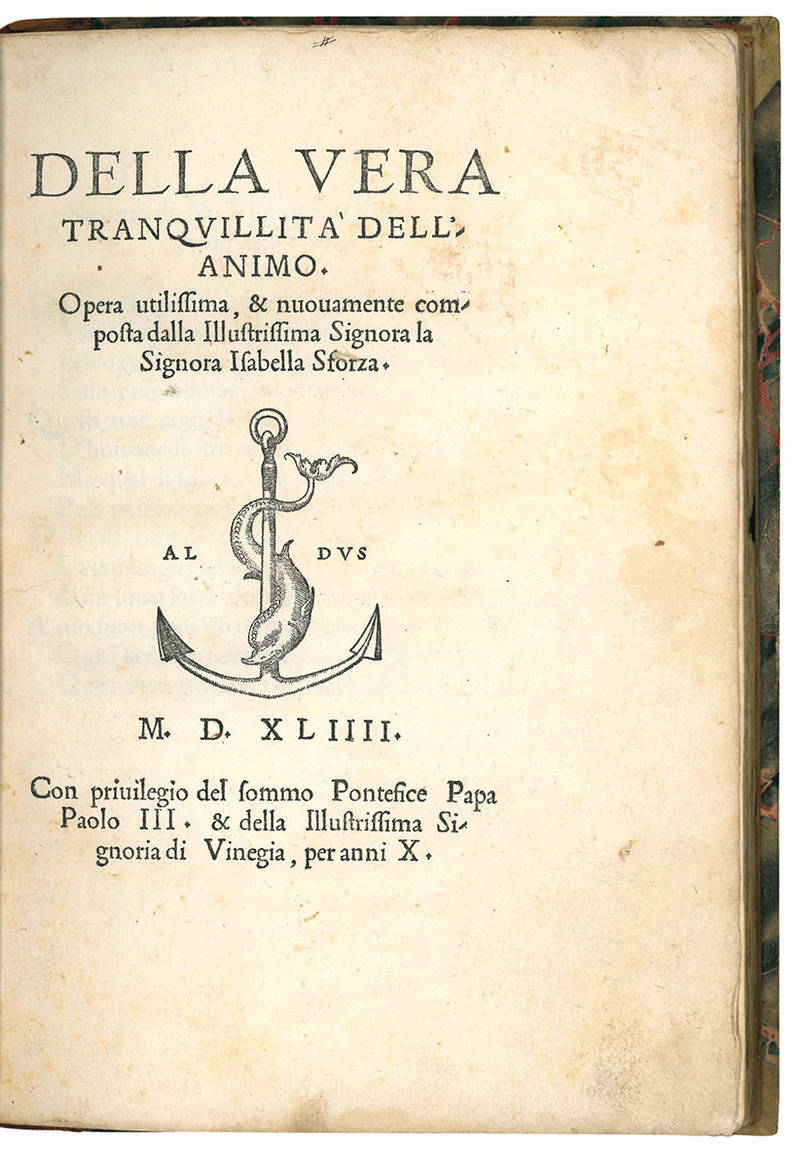

4to (212x145 mm). 53, [1] leaves. Collation: A-M4 N6. Printer's device on title page and last leaf verso. 19th-century half calf, gilt title along the spine (back repaired). Some light staining to the upper outer corner of the last 5 leaves, small repair to the upper outer corner of l. 49 (N1) not affecting the text, some light scattered foxing, but a good copy with wide margins.

FIRST EDITION. In the dedication letter to Otto Truchsess, bishop of Augsburg, dated Venice, May 10, 1544, Ortensio Lando writes under the pseudonym ‘Il Tranquillo': “[…] giunsi in Italia, & finalmente in Piacenza : dove, si come era di mio vecchio costume, visitai la Signora Isabella Sforza, alla quale per infiniti rispetti mi conosceva obbligatissimo: ne credo fusse questa mia visita senza voler divino: conciosia ch'io la ritrovassi tutta occupata in trattar simile argomento. & avendo con molte preghiere ottenuto di leggere così alla sfuggita i suoi divini componimenti, parvemi si dolcemente trattata questa materia, che subito con mio grande rossore feci disegno di ardere quanto ne havessi già circa tal soggetto scritto. […] Havendo io per tanto giudicato, essere gli scritti suoi di gran lunga alli miei superiori, contentandosi ella che per lo mio mezzo in luce uscissero” (leaves A3r-A4r) (‘I arrived in Italy, & finally in Piacenza: where, as was my old habit, I visited Signora Isabella Sforza, who, for infinite respects, knew me very obliged: I believe that my visit did not take place without divine will: knowing that I would find her all busy dealing with the same subject And, having obtained through many prayers a superficial reading of heir divine compositions, it seemed to me that this matter was treated so lovely, that I immediately, with a great blush, grasped the plan to burn everything I had written on the subject up to now [...] Having, therefore, considered that her writings were by far superior to mine, she accepted that they be published by my care').

Lando's paradoxical statement cannot disguise that he was in fact the author of Della vera tranquillità dell'anima. Already a contemporary source confirms that. In a copy (now in the Bavarian State Library) of the work in possession of the German humanist, orientalist and philologist Johann Albrecht Widmannstetter is a note attributing the work to ‘Hortensius Tranquillo, che in Napoli fu Hieremia di Landj amico del Saripando' (cf. C. Fahy, Per la vita di Ortensio Lando, in: “Giornale storico della letteratura italiana”, 142, 1965, pp. 246-248).

“In her discussion of Lando's impersonation of Isabella Sforza, Daenens [2000, see below], using a term employed by Gérard Genette, suggests we characterize the Vera tranquillità as an apocryphe consenti (that is, published with permission), with Sforza the garant du texte (textual guarantor): surely the impersonation was so extensive that Isabella must have been a party to it and the text must have had the authority of her assent” (M.K. Ray, Textual Collaboration and Spiritual Partnership in Sixteenth Century Italy: The Case of Ortensio Lando and Lucrezia Gonzaga, in: “Renaissance Quarterly”, 62, 2009, p. 710).

“Lungimirante appare la dedica al vescovo Otto Truchsess, del quale Lando vanterà più volte la liberalità nei propri confronti. Nelle manovre diplomatiche in vista del Concilio, Truchsess svolge il ruolo di grande mediatore, che il dedicatore non dimentica di sottolineare. Durante la sua missione a Cracovia nel 1542, il barone Truchsess era stato ospite di Bona Sforza e Sigismondo, ed aveva invitato il vecchio re a partecipare personalmente al Concilio. Vescovo di una città luterana, era tra gli uomini di Chiesa meglio informati delle ragioni dei protestanti e proprio per la sua riconosciuta autorevolezza il nunzio Varallo voleva fosse designato al Concilio. In qualità di cubicularius godeva la massima fiducia di Paolo III che nello dicembre dello stesso anno [1544] gli dette la porpora cardinalizia. Per la sua familiaritas con il pontefice e il camerlengo, Guido Ascanio Sforza, egli dava all'edizione un indiscusso prestigio. L'autrice, o la presunta autrice, non certo era ignota nei Palazzi Apostolici” (F. Daenens, Le traduzioni ‘Della vera tranquillità dell'animo, 1544: L'irriconoscibile Ortensio Lando, in: “Bibliothèque d'Humanisme et Renaissance”, LVI/3, 1994, p. 673).

“En 1544, sort de l'imprimerie Manuzio le traité Della vera tranquillità dell'animo. Opera utilissima e nuovamente composta dalla illustrissima Signora la Signora Isabella Sforza. Sur le papier, l'oeuvre est donc attribué à Isabella Sforza mais, à travers la lettre de dédicace à Otto Truchsess von Waldburg, signée par ‘Tranquillo', nous savons que Lando s'occupa d'éditer le traité. Isabella, fille de Giovanni Sforza, Seigneur de Pesaro et épouse de Cipriano del Negro, avait une réputation de femme savante et elle fut souvent louée par les auteurs se son époque, comme Lodovico Domenichi et Anton Francesco Doni [...] La paternité landienne de cette ouvrage [Della vera tranquillità dell'anima] a été acceptée unanimement depuis longtemps et il nous semble pas nécessaire de retracter tous les arguments en faveur de cette hypothèse. Outre les évidentes similitudes stylistiques, il suffit remarquer que deux chapitres du traité ressemblent beaucoup à deux chapitres des Paradossi... Le role d'Isabella dans cette oeuvre, reste néamoins une question sans réponse certaine. Sans aucun doute, Lando avait préalablement convenu cette publication avec elle, mais nous n'avons aucune possibilité de savoir si elle participa activement à sa conception. Par ailleurs, dans notre perspective, axée sur les techniques de promotion, ce qui nous intéresse est surtout la manière par laquelle cette fiction a été mise en scène par l'auteur. De cette initiative l'auteur pouvait tirer plus d'un avantage. Premièrement, il rendit hommage à sa protectrice, en recevant très probablement une bonne compensation de sa part. Cet ouvrage, en effet, renforça remarquablement la reputation d'Isabella comme femme savant. En même temps, en présentant comme l'éditeur de ce traité, il contribua aussi a sa propre renommé. L'hommage à des femmes mécènes à travers l'exaltation de leur érudition et de leur capacités littéraires était un topos qui était en train de se répandre rapidement à une époque ou commencèrent effectivement à émerger des écrivaines. Toutefois, il pourrait avoir une autre raison dans le choix de publier le traité sous le non d'une femme: Lando visait peut-être une nouvelle part du marché du livre, représentée justement par le public féminin, lequel aurait pu être particulièrement bienveillant à l'égard une oeuvre écrite par une autre femme. À ces aspect il faut aussi ajouter que l'autorité d'Isabella sur une oeuvre au contenu religieux aurait protéger l'auteur des accusations d'hérésie et faciliter l'impression du traité” (F. Greco, Autopromotion, paradoxe et réécriture dans l'oeuvre de Ortensio Lando, Diss., Grenoble, 2018, pp. 93-94).

“The treatise was published with the official sanction of a Farnese pope, though it expresses ideas very close to those in the Confessio Augustana: the total corruption of the human nature through the sin of Adam, the vanity of any human effort in the process of salvation, and faith that justifies. In 1544 these arguments on grace and merit were not in conflict with absolute loyalty to the pope, and the hopes of religious conciliation expressed in the dedication and in the text were undoubtedly shared at the highest levels of the Church. The ethical choices do seem more congruent with a Reformational mentality, and indeed after the Council of Trent these were violently challenged by the Church” (F. Daenens, Isabella Sforza: beyond the stereotype, in: “Women in Italian Renaissance Culture and Society”, L.Panizza, ed., Oxford, 2000, p. 49).

Born in Milan, Ortensio Lando studied there under Alessandro Minuziano, Celio Rodogino, and Bernardino Negro. He continued his studies at the University of Bologna and obtained a degree in medicine. For five years (1527 to 1531) he retired in different Augustinian convents (as Fra Geremia da Milano) of Padua, Genoa, Siena, Naples, and Bologna, studying various humanistic disciplines, among them Greek. In these years he became acquainted with the works of Erasmus and kept friends with various scholars with Evangelical inclinations as Giulio Camillo Delminio and Achille Bocchi. After a short stop in Rome, he preferred to leave Italy and settled at Lyon, where he worked as editor in the printing house of Sébastien Gryphe. Here he also met Étienne Dolet and published his first work Cicero relagatus et Cicero revocatus (1534). Then he began a wandering life and in the next twelve years he is found in Basel, where he published Erasmi funus (1540) and attracted the anger of the city's Reformed church. He visited France and was received at the court of King Francis I. He reappeared at Lyon in 1543, where he printed his first Italian and most successful book Paradossi (1543). He then visited Germany and claims also to have seen Antwerp and England. At Augsburg he was welcomed by the wealthy merchant Johann Jakob Fugger. In 1545 he is found in Piacenza, where he was received by Lodovico Domenichi and Anton Francesco Doni in the Accademia degli Ortolani. Then followed a decade of relative peace in which Lando's life became stabilized on Venetian territory. He was present at the opening of the Council of Trent and found a patron in bishop Cristoforo Madruzzo. In Venice he worked for various printers, mainly for Giolito, and often met Pietro Aretino, with whom he had already a correspondence since several years. In 1548 he translated Thomas More's Utopia, wrote the Commentario delle più notabili mostruose cose d'Italia (1548), and published the Lettere di molte valorose donne (1548), the first collection of letters by women. He was also very active in the coming years and published numerous works, in which he criticized the traditional scholarship and learning and in which he showed close sympathy with the Evangelical movement. In fact, all his writings appeared first in the Venetian indices of 1554 and later in the Roman Index of 1559 (cf. S. Seidel Menchi, Chi fu Ortensio Lando?, in: “Rivista Storica Italiana”, 106/3, 1994, pp. 501-564; see also S. Adorni Braccesi & S. Ragagli, Ortensio Lando, in: “Dizionario biografico degli Italiani”, vol. 63, Roma, 2004, pp. 451-459).

Isabella Sforza was the illegitimate daughter of Giovanni Sforza (1466-1510), Lord of Pesaro, upon whose death the duchy reverted to the church and this branch of the Sforza family died out with Isabella. Her father recognized her in his will (July 24, 1510), assigning her a dowry of 3000 ducats. With a brief of 18 August 1520, the Medici Leo X imposed to marry her to Cipriano Sernigi, a rich Florentine merchant of the art of wool, of proven Medicean loyalty. A long controversy on her dowry and the Sforza legacy ensued. During the imperial siege of the castle of Milan in 1526, Isabella was part of the restricted circle of informants in the Confederate camp and found herself facing risky missions - such as transmitting encrypted diplomatic missives - which she was called to account for in presence of Alfonso d 'Avalos, commander of the imperial army. In 1527 Isabella became a victim of one of Pietro Aretino's sordid literary intrigues, in which he presented her in two sonnets as the redeemer of his homosexual inclinations (cf. A. Luzio, Pietro Aretino nei primi suoi anni a Venezia e la corte dei Gonzaga, Torino, 1888, p. 23; see also, D. Romei, ed., Scritti di Pietro Aretino nel codice Marciano It. 66, Firenze, 1978, pp. 119-122; and Pietro Aretino, Frottole, D. Romei, ed., n. pl., 2019, p. 18). In early August 1532, during a quarrel, her husband was assassinated in Parma, in his presence, by Ottaviano Lampugnano, his procurator for many years, who managed to escape. Strongly compromised, Isabella was arrested and taken to the convent of S. Caterina, which she would have left only on bail, thanks to the mediation of the ducal envoys. She protested her innocence, wanted to be questioned and the case was closed at the end of the month. In 1544 appeared in Venice under her name, Della vera tranquillità dell'animo, edited by Ortensio Lando. Her letters included in the collection Lettere di molte valorose donne (1548), also edited by Ortensio Lando, greatly contributed to increase her reputation as a literary woman. From 1550 on she lived in Rome. She was summoned to appear before the Roman court of the Holy Office; the inquisitorial procedure is documented only in the Decreta, where it is titled as ‘causa Isabella Sforza Pallavicini'. In the congregation of January 25, 1560, presided over by Michele Ghislieri (later Pope Paul V), the first after the election of Pius IV, she was forbidden to leave the city, but the elements acquired by the Holy Office and the identity of the prosecution witness are not known. On April 3, 1560, after the reading of the trial, the judges of faith ruled for acquittal. Isabella died a year later (cf. M. E. Roffi Chinelli, Isabella Sforza e i letterati del suo tempo: per una ricognizione della presenza nella cultura piacentina del Rinascimento, Piacenza, 1992, passim; see also F. Daenens, Isabella Sforza: beyond the stereotype, in: “Women in Italian Renaissance Culture and Society”, L.Panizza, ed., Oxford, 2000, pp. 35-55).

Edit 16, CNCE26949; Adams, S-1044; Universal STC, no. 837258; A. Renouard, Annales de l'imprimerie des Aldes, Paris, 1834, p. 129, no. 1; P.J. Angerhofer & al., eds., In aedibus Aldi: The Legacy of Aldus Manutius and his Press,Provo, UT, 1995, pp. 78-79, no. 42.

[10761]