PMM 258

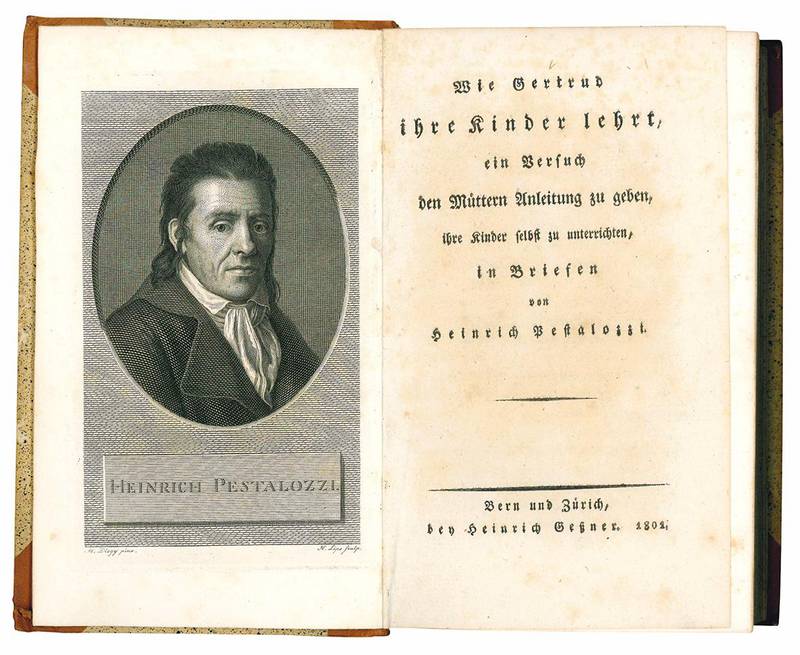

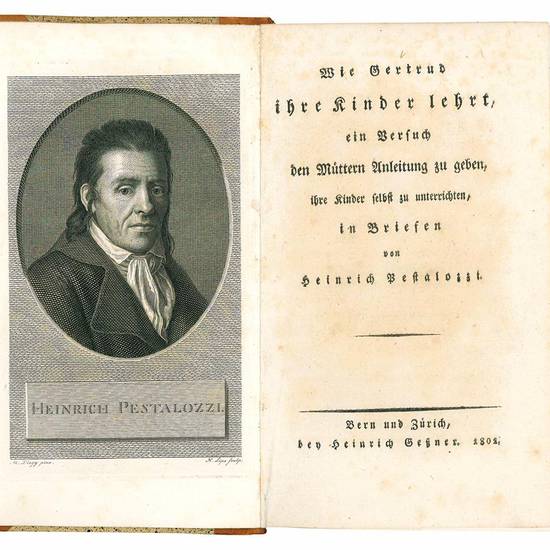

8vo (180x105 mm). Frontispiece with the author's portrait engraved by H. Lips after M. Diogg, pp. [2], 390. Contemporary half calf gilt, lettering piece on spine, sprinkled edges. Some light browning and foxing, one gathering towards the end more strongly browned, but a very good, extremely genuine copy with wide margins.

FIRST EDITION. “Pestalozzi had no training or special qualifications as a teacher […] In 1775, himself desperately poor, he turned his farm at Neuhof into an orphan asylum but in 1780 a combination of a lack of funds and the desertion of most of the children caused him to abandon the experiment. He next tried his hand at writing. A volume of aphorisms on the value of education, 1780, was succeeded by Lienhard und Gertrud (4 vols, 1781-7), which was a kind of romance with an educational motif. For the ten years from 1787 he returned to farming; but his passion for educational advance did not pass without notice. He corresponded with Fellenberg, the pioneer of agricultural institutes, and with Fichte who remarked on the coincidence of his ideas with those of Kant.

In 1798 Pestalozzi opened a second orphan asylum at Stans, where he had eighty pupils, several of whom he trained as pupil-teachers. One year later he was appointed to a primary school by the Swiss government at Burgdorf and it was here that ‘How Gertrude teaches her Children' was produced. The title is misleading, because the series of letters deals rather with the results than with the method of teaching, and Getrude herself does not appear. It is nevertheless an exhaustive exposition of Pestalozzi's principles with especial emphasis on the three R's. The most important and forward-looking of his ideas, which he stressed continually in practice as well as a precept, was that the true method of education is to develop the child, not to train him as one trains a dog. The pupil must be regarded as more important than the subject and the ‘whole man' must be developed.

In 1805 Pestalozzi opened his last school at Yverdun. Although, perhaps because, this school attracted visitors from all over Europe, Pestalozzi seems to have felt himself less at home in this school than in its unsuccessful predecessors.

It has been well said that he became a Swiss curiosity, visited by tourists as they visited a glacier. His influence has been felt throughout the world and he is commemorated in the Pestalozzi villages where the children of war fugitives are cared for. Not less important than the institution of such ideas was his pungent criticism of the absence of standards in the recruitment of teachers. The miserable pay and wretched conditions attracted ‘corrupt artisans, discharged soldiers, degraded students, and, in general, persons of questionable morality and education'. Mr Squeers affords ample evidence that such conditions were not abolished by Pestalozzi's efforts: but he pointed the way” (Printing and the Mind of Man, p. 156).

PMM, 258; Borst, 905; Israel, I, 24; Brieger, 1879; Neufforge, 414.

[9761]