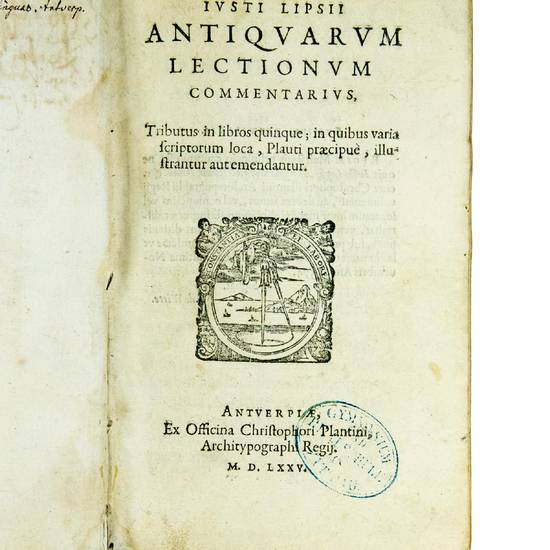

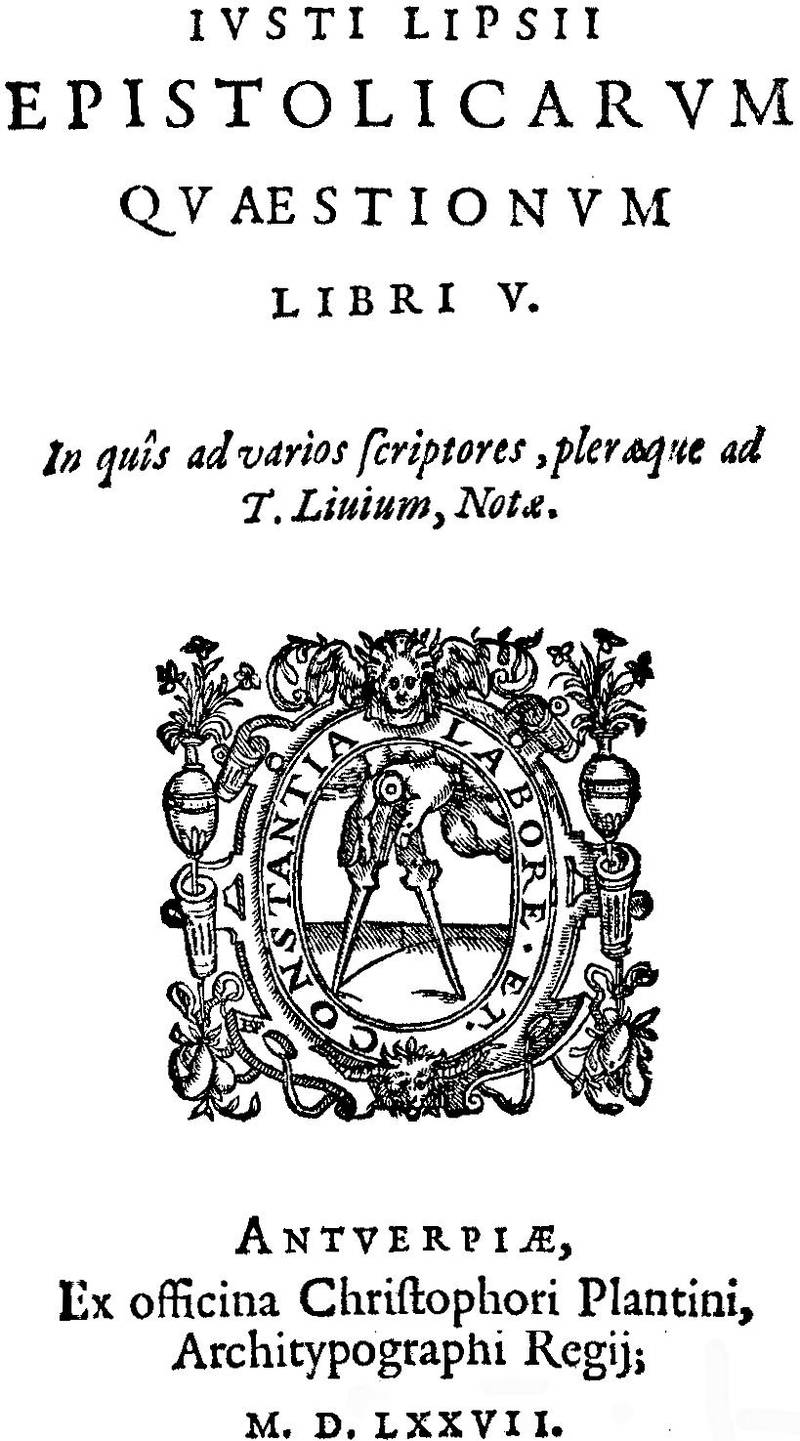

Epistolicarum quaestionum libri V. In quîs ad varios scriptores, plaeraque ad T. Livium, Notae. Antwerp, Christoph Plantin, 1577. [bound with:] Liber de rebus per epistolam quæsitis [...] adjuncta est Francisci Campani Quaestio Virgiliana. Paris, Henri Estienne, 1567

Autore: LIPSIUS, Justus (1547-1606)-PARRASIO, Aulo Giano (1470-1521)

Tipografo:

Dati tipografici:

Two works in one volume, 8vo.

I. LIPSIUS:

(16), 231 pp. †8, A-O8, P4. With the printer's device on the title-page. Contemporary limp vellum.

Bibliotheca Belgica, L-489; Voet, no. 1554; A. Gerlo, M.A. Nauwelaerts & H.D.L. Vervliet, eds., Iusti Lipsi Epistolae, (Bruxelles, 1978-1983), I, p. 14; G. Tournoy, J. Papy, & J. de Landtsheer, eds., Lipsius en Leuven. Catalogus van de tentoonstelling in de Centrale Bibliotheek te Leuven, 18 september - 17 oktober 1997, (Leuven, 1997), p. 59, no. 11a.

FIRST EDITION of this collection of letters (mostly fictitious) with critical comments on a great number of passages from Titus Livius and other classical Greek and Latin authors. The work is divided into five books, containing respectively 22, 26, 24, 28 and 26 letters. It was reprinted in 1585. The work is dedicated to Joannes Scheyf, chancellor of Braband (Leuven, August 18, 1576).

“On 10 February 1576, Plantin told Pithou that he had been invited by Lipsius to attend the latter's promotion to doctor in Louvain. At this occasion Lipsius had spoken with him about his plans for the publication of several works, including Quaestiones epistolae[...] In a letter of 1 July 1576 to Pulmannus, Lipsius himself declares he is working hard on the publication. A month later, however, he had some doubts whether, owing to the troubled time, Plantin would be able to publish his book” (L. Voet, The Plantin Press (1555-1589). A bibliography of the works printed and published by Christopher Plantin at Antwerp and Leiden, Utrecht, 1980-1983, III, p. 1382).

(Liber Primus:)

Cujas, Jacques (p. 1)

Scaliger, Joseph Justus. July 29, 1575 (p. 3)

Sigonio, Carlo (p. 4)

Camerarius, Joachim (p. 6)

Lernutius, Janus (p. 7)

Muret, Marc-Antoine (p. 14)

Carrio, Ludovicus (p. 14)

Scaliger, Joseph Justus (p. 17)

Pighius [Wynants], Stephanus (p. 18)

Giselinus, Victor (p. 20)

Roaldus, Franciscus (p. 21)

Torrentius [Van der Beken], Laevinus (p. 22)

Langius [Delanghe], Carolus (p. 23)

Lernutius, Janus (p. 25)

Pithou, Pierre (p. 26)

Busbecq, Ogier Ghislain de (p. 28)

Plantin, Christoph. Köln, March 5, 1574 (p. 29)

Puteanus [Dupuy], Claudius (p. 30)

Danieli, Petrus (p. 33)

Oiselius [Loisel], Antonius (p. 34)

Scaliger, Joseph Justus (p. 36)

Pithou, Pierre (p. 37)

(Liber secundus:)

Laurin, Marco & Laurin, Guido (p. 41)

Carrio, Lodovicus (p. 45)

Susius, Jacobus (p. 46)

Bryardus, Nicolaus (p. 48)

Orsini, Fulvio (p. 49)

Giselinus, Victor (p. 50)

Fabrus [Faber], Petrus (p. 52)

Meetkercken, Adolf van (p. 53)

Pulmannus [Poelman], Theodoor (p. 54)

Giselinus, Victor (p. 56)

Sigonio, Carlo (p. 58)

Nansius, Franciscus (p. 59)

Pantinus [Pantin], Pierre (p. 60)

Schetus [Schetz], Gaspar (p. 61)

Berot, Jean (p. 63)

Giselinus, Victor (p. 64)

Brisson, Barnabé (p. 66)

Schott, Andreas (p. 67)

Falkenburg, Gerard (p. 70)

Cruquius [Cruyck], Jacobus (p. 71)

Goltius, Hubertus (p. 72)

Bryardus, Nicolaus (p. 74)

Turconius [Lannoy, Philippe de] & Maldeghemius [Maldegem, Philippe] (p. 78)

Carrio, Lodovicus (p. 79)

Giselinus, Victor (p. 83)

Leunclavius, Joannes (p. 86)

(Liber tertius:)

Susius, Jacobus (p. 89)

Pithou, Pierre (p. 90)

Lernutius, Janus (p. 92)

Sigonio, Carlo (p. 94)

Carrio, Ludovicus (p. 95)

Scaliger, Joseph Justus (p. 96)

Crato, Joannes (p. 98)

Divaeus [Dieve], Piet van (p. 100)

Giselinus, Victor (p. 101)

Camerarius, Joachim (p. 102)

Falkenburg, Gerard (p. 104)

Modius, Franciscus (p. 106)

Fleming, Joannes (p. 107)

Muret, Marc-Antoine (p. 108)

Carrio, Ludovicus (p. 110)

Valerius [Wouters], Cornelis (p. 112)

Falkenburg, Gerard (p. 113)

Breugel, Willem (p. 115)

Hunnaeus [Huens], Augustin (p. 116)

Giselinus, Victor (p. 118)

Delrio, Martino Antonio (p. 120)

Pighius [Wynants], Stephanus (p. 121)

Carrio, Ludovicus (p. 123)

Giselinus, Victor (p. 125)

(Liber quartus:)

Arias Montanus, Benedictus (p. 129)

Sambucus, Joannes (p. 131)

Raphelengien, Francicus (p. 133)

Ortelius, Abraham (p. 134)

Pighius [Wynants], Stephanus (p. 136)

Bryardus, Nicolaus (p. 137)

Livinaeus [Lievens], Jan (p. 138)

Giselinus, Victor (p. 140)

Florentius, Nicolaus (p. 142)

Scaliger, Joseph Justus (p. 144)

Manuzio, Paolo (p. 146)

Lernutius, Janus (p. 147)

Pithou, François (p. 148)

Laurin, Guido (p. 150)

Muret, Marc-Antoine (p. 155)

Borssele, Maximiliaan van (p. 156)

Giselinus, Victor (p. 158)

Carrio, Ludovicus (p. 160)

Falkenburg, Gerard (p. 162)

Giphanius, Obertus (p. 163)

Giselinus, Victor (p. 166)

Scheyf, Joannes (p. 170)

Schott, Andreas (p. 173)

Giselinus, Victor & Lernutius, Janus (p. 174)

Canter, Theodor (p. 176)

Dousa, Janus (p. 178)

Wamesius, Joannes (p. 185)

Divaeus [Dieve], Piet van (p. 187)

(Liber quintus:)

Sigonio, Carlo (p. 190)

Orsini, Fulvio (p. 191)

Lernutius, Janus (p. 193)

Estienne, Henri (p. 194)

Papius [Pape], André de (p. 195)

Carrio, Ludovicus (p. 197)

Tayus, Jacobus (p. 198)

Schott, Andreas (p. 199)

Pamelius [Pamele], Jacques de (p. 201)

Susius, Jacobus (p. 203)

Divaeus [Dieve], Piet van (p. 205)

Giselinus, Victor (p. 206)

Falkenburg, Gerard (p. 209)

Modius, Franciscus (p. 210)

Muret, Marc-Antoine (p. 212)

Lannoy, Philippe de (p. 215)

Valerius [Wouters], Cornelis (p. 217)

Ramus, Joannes (p. 219)

Pithou, Pierre (p. 219)

Vliegerus, Aegidius (p. 220)

Pighius [Wynants], Stephanus (p. 222)

Raphelengien, Franciscus (p. 224)

Sturio, Nicolaus (p. 225)

Lernutius, Janus (p. 226)

Giselinus, Victor (p. 227)

to the Reader (p. 228)

Born near Louvain in the town of Overlise, Justus Lipsius distinguished himself as a student of the classics first at the Jesuit college at Cologne and subsequently at the university in Louvain. Shortly after completing his studies, he published a precocious volume of Variae Lectiones (1569), a collection of philological observations on classical texts. Written in a polished Ciceronian style and dedicated to no less a figure than Cardinal Granvelle, chief minister of Philip II in the Low Countries, the volume quickly captured the attention not only of the powerful prelate but also of Europe's scholars.

This initial work had significant and lasting effects on Lipsius' career; the most immediate was his appointment as Latin secretary to Granvelle, who took the young man to Rome, where he was introduced to international power politics as well as to the treasures of Italian libraries, including the Vatican's. An equally significant result of the cardinal's patronage was the opportunity it afforded Lipsius to make the acquaintance of Marc-Antoine Muret, the French scholar who was perhaps the most famous Latinist of his age.

A recent convert to the anti-Ciceronian movement, Muret in turn made a convert of Lipsius. The first fruit of this interest was Lipsius' famous edition of Tacitus (1575), and its culmination was Politicorum libri sex (1589), a compilation of classical political wisdom directed explicitly at the social and religious crises of the sixteenth century. These works won him a reputation as a ‘politician', or student of prudentia, which was never equaled or corrected, at least in Italy, by the fame of his later works.

A corollary interest was the style and philosophy of Seneca. Lipsius' most famous and influential work, De constantia (1584), is a synthesis of Christianity and Stoic philosophy. The crowning achievement of his career are two studies of Stoicism, Manuductio ad stoicam philosophiam and its sequel Physiologia stoicorum (both 1604), and his monumental edition of Seneca (1605).

After two years in the service of the cardinal, Lipsius returned briefly to Leuven, only to leave again in 1571, apparently fearing the strife that had broken out anew between his countrymen and their Spanish rulers. He went to the Viennese court of Maximilian II, where he met such renowned literary figures as Ogier Busbecq, Joannes Sambucus, Joannes Crato, and Stephanus Pighius, who urged that he stay in Vienna. He was unable to find the kind of patronage for which he had hoped, however, and he moved on to Bohemia, Meissen, and Thuringia. While in Thuringia, news of continued turmoil in Brabant deterred his return home, so he secured a recommendation from the Protestant scholar Joachim Camerarius, whom he had met in Leipzig, and this led to an invitation from the Duke of Saxe-Weimar to serve as professor of history at the Lutheran University of Jena in 1572.

Popular among students, Lipsius aroused the jealousy of elder colleagues and the suspicion of Protestant authorities. In March 1574, he left Jena for Cologne and evidently made his peace with the Church. It was in Cologne that he wrote five books of Antiquae lectiones, which are almost exclusively concerned with an enthusiastic examination of Plautus. After a few months, Lipsius returned to Leuven, and in 1576 he proceeded to the degree of doctor of laws, an undertaking that has been ascribed to his association with Muret and an interest in jurisprudence derived from Tacitus. In addition to resuming his work on Tacitus during this brief residence in his homeland, he also published his important Quaestiones epistolicae (1575).

But Lipsius was not yet to find peace. In 1578, with the news of the victory of Don Juan of Austria at Gembloux, he again became apprehensive at the prospect of an invasion by Spanish troops. He fled Louvain, and Spanish soldiers did indeed ransack his deserted house, confiscating and destroying his books and papers. He took brief refuge in the Antwerp home of his friend and publisher, Christopher Plantin. Then, in 1579, he accepted the temporary position of professor of history and law at the Leiden University.

Notwithstanding its explicitly Calvinist make-up, Leiden was a remarkably open university in the beginning, and in Holland Lipsius found a haven from his home province for nearly thirteen years. While there he published his Electa (1580); his Satyra Menippaea: Somnium (1581); his Saturnalia (1582); his De Amphitheatro (1584); his De Amphitheatris quae extra Romam (1584); notes on Valerius Maximus, Seneca, and Velleius Paterculus; and his De recta pronuciatione Latinae Linguae (1586); as well as the major works on constancy and politics. It was there, also, that he delivered the lectures on letter-writing that later became Epistolica institutio of 1591.

By 1591, however, the atmosphere, if not the statutes, of Leiden had become more stridently Calvinist, and Lipsius returned to the southern provinces of the Low Countries, where he was again reconciled to the Catholic Church, largely through the good offices of his boyhood masters, the Jesuits, and he accepted the post of professor of Latin at Leuven. He remained in Leuven for the rest of his days, resisting numerous appeals from foreign courts and especially from Italian churchmen (cf. M. Laureys, ed., The World of Justus Lipsius: A Contribution Towards his Intellectual Biography: Proceedings of a colloquium held under the auspices of the Belgian Historical Institute in Rome, Rome, 22-24 May 1997, Bruxelles, 1998, passim; and H.D.L. Vervliet, Lipsius' jeugd, 1547-1578: analecta voor een kritische biografie, in: “Mededelingen van de Koninklijke Vlaamsche Academie voor Wetenschappen, Letteren en Schone Kunsten van België, Klasse der Letteren”, 31/7, 1969, pp. 9-12).

II. PARRASIO:

(8), 272, (8) pp. ¶4, a-r8, s4. Contemporary limp vellum.

Adams, P- 353; P. Chaix, A. Dufour & G. Moeckli, eds., Les livres imprimés à Genève de 1550 à 1600, (Genève, 1966), p. 67; J. Kecskeméti & al., eds., La France des Humanistes. Henri II Estienne, éditeur et écrivain, (Turnout, 2003), no. 56; A.A. Renouard, Annales de l'Imprimerie des Estienne, (Paris, 1843), p. 130, no. 7; F. Schreiber, The Estiennes. An annotated Catalogue of 300 Highlights of their various Presses, (New York, 1982), no. 170.

FIRST EDITION of Parrasio's philological letters, edited by the French humanist printer Henri Estienne (1531-1598) and dedicated to the Italian critic and poet Lodovico Castelvetro (ca. 1505-1571), who at that time lived in exile at Geneva, victim of the Italian inquisition (cf. C. Lastraioli, Il fuoco sotto la cenere: Lodovico Castelvetro e la Francia, in: “Lodovico Castelvetro: letterati e grammatici nella crisi religiosa del Cinquecento”, L. Firpo & G. Mongini, eds., Firenze, 2008, p. 176).

Henri Estienne used for his edition an autograph manuscript by Parrasio now in the Vatican Library (Vat. Lat. 5233), in whose inventory it is registered since 1633. It had been presumed that is was previously owned by Paolo Manuzio. However, Estienne obtained the manuscript from Giuseppe Giova, secretary to Vittoria Colonna since 1525. Giova entered the Valdesian circles in Naples and later (1561) left Italy for Lyon. In 1568 he was officially condemned for heresy by the Italian inquisition. How he came into possession of Parrasio's manuscript is not known.

Parrasio's intention to write the present work goes back to the first months of 1508, when he was in Milan. Apparently the work was ready for print a year later, but external circumstances prevented its publication.

Parrasio “voleva dare risonanza al suo metodo filologico e alla sua attività di editore e insegnante. Nei Quaesita, al di là dei risultati puntuali su questo e quel punto, Parrasio faceva suo quel metodo nuovo che era stato introdotto nella filologia da Angelo Poliziano e che egli aveva assorbito dapprima a Cosenza, alla scuola di Tideo Acciarino, che aveva avuto contatti col Poliziano, e poi a Napoli, alla scuola di Francesco Pucci, che fu allievo del Poliziano, un metodo che prevedeva innanzitutto il confronto della lezione tradita sui codici. Parrasio dichiara esplicitamente di fondarsi sempre sulla collazione degli antichi esemplari, alla quale ritiene opportuno affiancare lo iudicium, ma di posporre comunque quest'ultimo alla lezione tradita dagli antichi manoscritti [...] Ma a progettare l'opera Parrasio fu spinto anche da motivi più contingenti. Occorreva riscattare la propria dignità professionale dopo le calunnie del Minuziano e dei letterati che ruotavano attorno a lui e, contemporaneamente, omaggiare quanti a Milano gli erano rimasti vicini, si erano schierati a suo favore e lo avevano protetto” (L. Ferreri, Genesi e trasmissione del ‘De rebus per epistolam quaesitis' di Aulo Giano Parrasio, in: “AION. Annali dell'Università degli Studi di Napoli «L'Orientale»”, XXVII, 2005, pp. 67-68).

“Die meisten der Schreiben in Parrasios Kollektion De rebus per epistolam quaesitis waren an einflussreiche Mitglieder der kultivierten Vicentiner Patrizierschicht adressiert: hinter einer solch scheinbar urbanen Reverenz vor den potentiellen Mäzenen in der Provinz knüpft der Autor in Wirklichkeit mit professioneller Gründlichkeit an die von Polizians ausgelösten philologischen Diskussionen an” (B. Marx, Zur Typologie lateinischer Briefsammlungen in Venedig vom 15. zum 16. Jahrhundert, in: “Der Brief im Zeitalter der Renaissance”, F.J. Worstbrock, ed., Weinheim, 1983, p. 147).

Lascaris, Joannes (p.1)

Thyeneus, Galeatius (p. 5)

Pagello, Bartolomeo (p. 8)

Thyeneus, Galeatius (p. 11)

id. (p. 14)

Bonfio, Luca (p. 16)

Valdo, Augusto (p. 17)

Leonico, Bartolomeo (p. 18)

Veienti, Paulo (p. 19)

Poncher, François (p. 21)

Aculeus, Petreius (p. 22)

Ivianus, Ludovicus (p. 24)

Macer, Vicentius (p. 25)

Corniger, Tatius (p. 26)

Archangelus Claravallensis (p. 26)

id. (p. 27)

Biffo, Giovanni (p. 28)

Moretto, Antonio (p. 28)

Plegapheta, Hieronymus (p. 32)

[Inghirami] Phaedrus, T[ommaso] (p. 34)

Burgo, Girolamo (p. 36)

Leoniceno, Bernardino (p. 37)

Thyeneus, Hieronymus (p. 38)

Pagnanus, Ambrosius (p. 39)

Leoniceno, Tamisio (p. 41)

Iamchino, Vincenzo (p. 43)

Ricio, Bruto (p. 44)

Chalchondylas, Basilius (p. 45)

Zuffatus, Ludovicus (p.46)

Macro, Alessandro (p. 48)

Ritio, Tamisio (p. 50)

Gallus, Antonius (p. 51)

Pico, Marcello M[arco] (p. 51)

Blandario, Evangelista (p. 52)

Porto, Alessandor (p. 54)

Bruno, Giovanni (p. 56)

Trissino, Giovan Giorgio (p. 57)

Tarsia, Vincenzo (p. 62)

Caesario, [Giovanni] Antonio (p. 66)

Pulianus, Andreas (p. 67)

Pedacius, Crassus (p.68)

Thyeneus, Alexander (p. 69)

Morellus, Jo[annes] Baptista (p. 71)

Varro, Jac[obus] (p. 72)

Barbarano, Alberto (p. 74)

Nicolaus sacerdos Vicentinus (p. 75)

Modestus sacerdos Vicentinus (p. 76)

Capra, Lysius (p. 77)

Chieregati, Girolamo (p. 78)

Mercatore, Tamisio (p. 80)

N. (p. 81, Libet Horatiano carmine)

id. (p. 82, Papinii carmina)

id. (p. 84, Dixin' ego tibi)

id. (p. 86, Nisi te supra)

id. (p. 87, Etsi statueram nulla)

Amiternino, Antonio (p. 89)

N. (p. 97, Petis ut iudicium)

id. (p. 99, Luctaris, ut video)

id. (p. 121, Quaeris ex me)

id. (p. 124, Scribis te mirari)

Capilupi, Camillo (p. 129)

Hadrianus [Cornetanus, i.e. Castellesi, Adriano] cardinalis (p. 132)

id. (p. 134)

There follow other commentaries by Parrasio (pp. 135-224) and the Quaestio virgiliana by Francesco Campana (1491-ca. 1546), which was first published at Bologna in 1526 with a dedication to Ercole Gonzaga (February 20, 1526, in the present edition wrongly dated 1536).

Aulo Giano Parrasio was born near Cosenza in Calabria and began his career in Naples, where he became friendly with Giovanni Pontano and his circle. Forced from Naples by the French invasion, he moved to Rome entering the academy of Paolo Cortesi. Here he also became acquainted with Tommaso Inghirami and Pierio Valeriano. Later he moved to Milan (where he married the daughter of the Greek humanist Demetrius Chalcondylas), to Venice, to Vicenza, and back to Cosenza - each move being forced either by external circumstances or by academic quarrels. In 1514 pope Leo X called him to Rome as professor of eloquence, a post he had to abandon because of ill health a few years later. He then retired to Cosenza on a small pension from the pope.

Parrasio was certainly one of the greatest humanist commentators on the ancient poets. Unlike many scholars of his day, Parrasio established his textual criticism on the systematic, indeed obsessive, collection and study of codices owned and annotated by the founding fathers of humanism, from Petrarch to Barzizza, from Loschi to Decembrio. His library included manuscripts that once belonged to such illustrious contemporaries as his father-in-law, Demetrius Chalcondylas, editions edited or commented on by such accomplished philologists as Calderini and Beroaldo, and theoretical treatises of Valla, Merula, Poliziano, and Pontano, whose margins bear the results of his researches in his unmistakable hand (cf. U. Lepore, Per la biografia di Aulo Giano Parrasio (1470-1521), in: “Biblion”, I/1, 1959, pp. 27-44; see also F. D'Episcopo, Aulo Giano Parrasio: fondatore dell'Accademia Cosentina, Cosenza, 1982, passim; and A. Greco, Aulo Giano Parrasio, in: “Letterature comparate, problemi e metodo: Studi in onore di Ettore Paratore”, Bologna, 1981, III, pp. 1329-1341).

Also bound with: Justus Lipsius, Antiquarum lectionum commentarius, Antwerp, Plantin, 1575; and: Theodor Zwinger, Methodus Rustica Catonis atq. Varronis, Basel, Perna, 1576.

[9029]

![Epistolicarum quaestionum libri V. In quîs ad varios scriptores, plaeraque ad T. Livium, Notae. Antwerp, Christoph Plantin, 1577. [bound with:] Liber de rebus per epistolam quæsitis [...] adjuncta est Francisci Campani Quaestio Virgiliana. Paris, Henri Epistolicarum quaestionum libri V. In quîs ad varios scriptores, plaeraque ad T. Livium, Notae. Antwerp, Christoph Plantin, 1577. [bound with:] Liber de rebus per epistolam quæsitis [...] adjuncta est Francisci Campani Quaestio Virgiliana. Paris, Henri](https://www.libreriagovi.com/typo3temp/pics/7c58e43c2e.jpg)