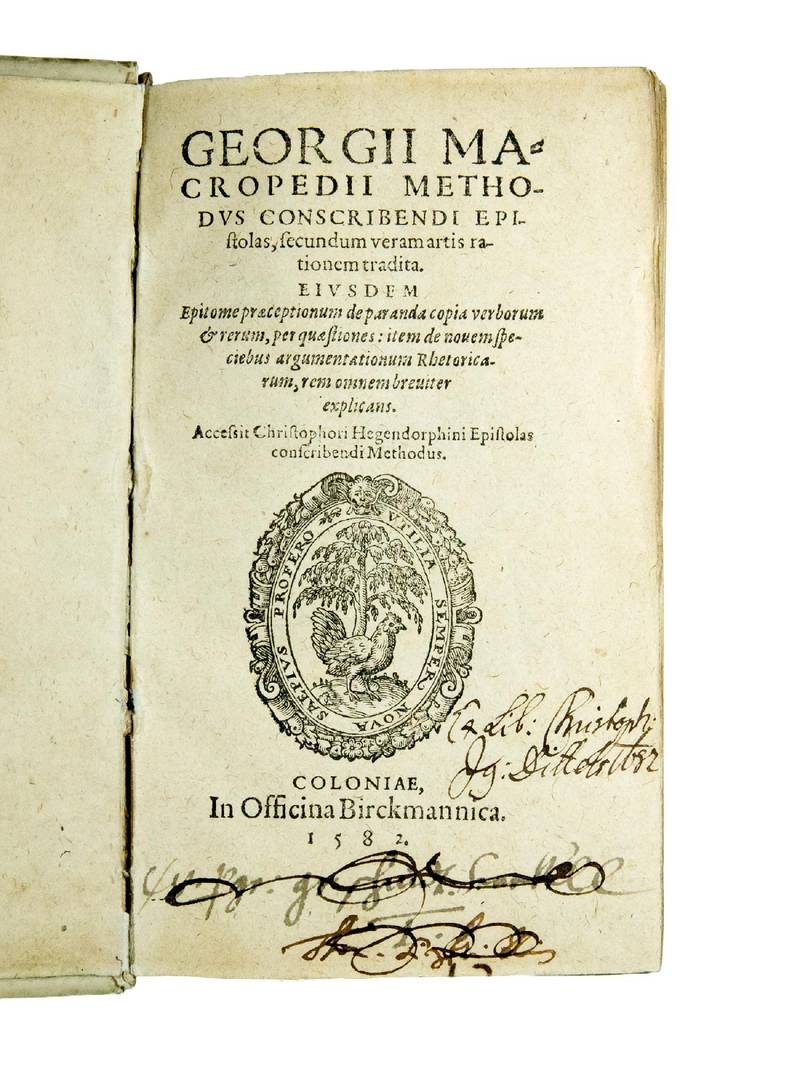

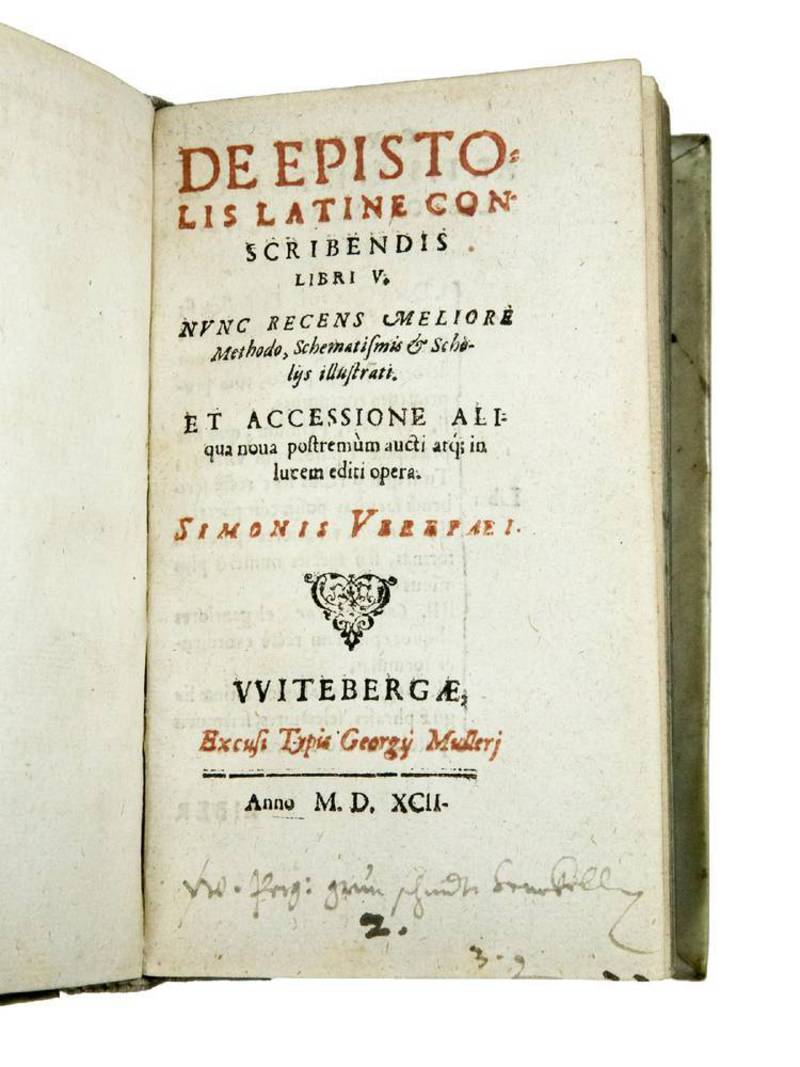

Methodus conscribendi epistolas, secundum veram artis rationem tradita. Eiusdem Epitome praeceptionum de paranda copia verborum & rerum, per quaestiones: item de novem speciebus argumentationum Rhetoricarum, rem omnem breviter explicans. Accessit Christophori Hegendorfini Epistolas conscribendi Methodus. Köln, Officina Birckmannica, 1582. [Bound with:] Epistolarum Familiarium Formulae, ex omni erudita latinitate collectae et contextae, et accomodatae ad haec nostra tempora, & de quibus ferè in comuni hominum vita, seorsim verò in scholis, eruditi ad eruditos scribimus & dicimus, ac amici cum amicis familiariter colloquimur, et distributae in tria causarum sive materarum genera. Leipzig, Abraham Lamberg, 1591. [Bound with:] De epistolis latine conscribendis libri V. Nunc recens meliorè Methodo, Schematismis & Scholijs illustrati. Et accessione aliqua nova postremùm aucti atq(u)e in lucem editi opera. Wittenberg, Georg Müller, 1592

Autore: MACROPEDIUS, Georgius (Joris van Langhveldt, 1475-1558)-NEANDER, Michael (1525-1595)-VEREPAEUS, Simon (1522-1598)

Tipografo:

Dati tipografici:

Three works in one volume, 8vo.

I. MACROPEDIUS:

(2), 123 [i.e. 125], (1) leaves. A-Q8 (Q8 is a blank). With the printer's device on the title-page. Contemporary vellum over boards, blind-stamped fillets on the panels with the lettering P.V.B 1597 on the front panel, old entries of ownership on the title-page. Ex libris Franz Pollak-Parnau.

Catalogo unico, IT\ICCU\BVEE\021641.

RARE EDITION. This is a literal reprint of the Birckmann edition of 1568. Macropedius' most successful textbook, dedicated to the youth of Utrecht, on the art of letter writing was first published as Epistolica at Antwerp by Hillen in 1543 and after his death under the title Methodus conscribendi epistolas in 1561 at Dillingen. Added to this edition for the first time was the tract Epitome praeceptionum de paranda copia verborum & rerum, per quaestiones, which was falsely attributed to Macropedius, and, in fact, was written by Johannes Rivius (1500-1553) and first published at Wesel in 1548.

Printed at the end is also Christoph Hegendorff's (1500-1540) Modus conscribendi epistolas; this is a literal reprint of the edition that appeared in Hagenau in 1526.

“Macropedius' Epistolica is divided into two parts, the first treating the invention, the second, disposition and elocution. Although Macropedius does not acknowledge Erasmus, in the first part he draws on the Opus de conscribendis epistolis in prescribing forms of greeting, address, and farewell and in classifying letters. He names five categories; demonstrative, deliberative, judicial, didascalicum or dialecticum (Erasmus' letter of discussion), and indicativum (Erasmus' extraordinary or family class). Macropedius provides his own sample letters, and he is more rigid in applying rhetorical precepts to letter writing than Erasmus. Although he concedes that the structure of the letter varies with the type of argument, he nevertheless defines for each type except the familiar or formal structure based on the divisions of the oration. This is a procedure that Erasmus had criticized in Francesco Negro's De modo epistolandi. Macropedius emphasizes art much more, individual judgment and the demands of decorum much less, than Erasmus” (J. Rice Henderson, Humanism and the Humanities. Erasmus's ‘Opus de conscribendis epistolis' in Sixteenth Century Schools, in: “Letter-Writing Manuals and Instruction from Antiquity to the Present”, C. Poster & L.C. Mitchell, eds., Columbia, SC, 2007, p. 158).

Georgius Macropedius was born as Joris van Langhvelt in Gemert (North Brabant, the Netherlands). Little is known about his boyhood. After having attended the parish school he moved to s'-Hertogenbosch. Here, he attended the local grammar school and lived in one of the boarding-houses of the Brothers of the Common Life. In 1502, at the age of fifteen, he became a member of the fraternity and prepared for a career in teaching. About ten years later he was ordained and started teaching Latin at the municipal grammar school. In the years 1506–1510 he had already started writing Latin plays for his students. The first drafts of his drama Asotus (The Prodigal Son) date from this period. He took on a classic name, as was the custom among sixteenth century humanists: Joris became Georgius and Van Langhvelt was translated into Macropedius.

In 1524 he was appointed headmaster of St. Jerome's in Liège. In 1527 Macropedius returned to 's-Hertogenbosch and by the end of 1530 he had already moved to Utrecht, and, reputed to be a loyal Roman Catholic, was appointed headmaster. He transformed St. Jerome's in Utrecht into the most famous school of the country. He taught Latin, Greek, poetry, rhetoric, and possibly Hebrew, mathematics, rhetoric, and theory of music too. Every year he composed both text and music of a lengthy Latin school song. At St. Jerome's he wrote most of his Latin textbooks and plays, which were published not only in Utrecht, but also in Antwerp, Basel, Cologne, Frankfurt, 's-Hertogenbosch, Paris, and in London.

In the years 1552–1554 his collected works were revised and edited in two volumes in Utrecht: Omnes Georgii Macropedii Fabulae Comicae. The songs were now printed together with their music. Afterwards, he only wrote one more play: Jesus Scholasticus. In 1557 or 1558 he resigned as headmaster of the school, and left Utrecht to return to his native soil, Brabant. Here he lived for another year in the House of Brothers of the Common Life in 's-Hertogenbosch. He died at the age of 71 in this town during a period of plague in July 1558, and was buried in the Brothers' church.

After his death his grateful former students erected a monumental tomb there, with an epitaph. They had a portrait painted of their beloved master, which was hung over the tomb. Both tomb and painting have disappeared and so has the church. His schoolbooks proved Macropedius to be a man of great humanist culture and a follower of Erasmus. He knew all about the seven Free Arts and the Three Languages Latin, Greek and Hebrew. He was very familiar with the classic Greek and Roman literature, with the Bible and the writings of the Fathers of the Church as well. Many reprints of his textbooks in the Netherlands, in Germany, in France, and in England prove that Macropedius' activities were highly esteemed by his contemporaries and by the next generation of humanists as well. By writing his books and his teachings, Macropedius contributed very much to the successful humanist educational reform in the first part of the sixteenth century. He indefatigably promoted Greek, not only the reading of the New Testament but also the study of the works of the classic Greek authors. Macropedius, however, owes his greatest fame to his twelve plays. In the Netherlands and in Germany he was the first, the most productive, and the best Latin playwright (cf. H. Giebels & F. Slits, Georgius Macropedius 1487–1558. Leven en Werken van een Brabantse humanist, Tilburg, 2005, passim).

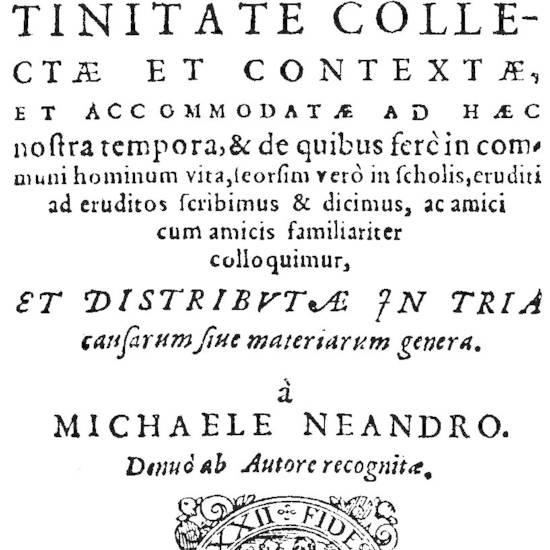

II. NEANDER:

(16), 141, (2) pp. )(8, A-K8 (K8 is a blank). With the printer's device on the title-page. Contemporary vellum over boards, blind-stamped fillets on the panels with the lettering P.V.B 1597 on the front panel, old entries of ownership on the title-page. Ex libris Franz Pollak-Parnau.

VD 16, N-370.

SECOND EDITION. This is a reprint of the first edition printed at Eisleben by Urban Gaubisch in 1586 with the same dedicatory letter to Lorenz Rhodomann, dated from Ilfeld, December 25, 1586.

Neander's intention was to give to his pupils at the school of Ilfeld a comprehensive textbook of phrases (mostly in Latin and Greek, and with a few in German), selected from the most renowned authors of antiquity, to improve both colloquial and epistolary style: “Continet autem Phrases eruditiores ac elegantiores pleraque, quibus in dicendo & scribendo de Argumentis & materiis, de quibus docti inter se scribere solent, conferre & colloqui, fere utimur, ita contextas & distribuitas in tria causarum genera, eoque contextu & Epistolae tali formula, ut appareat ita esse principio contextas & scriptas ab illis auctoribus eruditis, de quorum elegantijs singulae epistolarum formulae sunt contextae” (l. )(2r).

The phrases are grouped according to three categories of letters: demonstrative, deliberative, and judicial, each with several subcategories. At the end are printed a few letters by Neander's friends and his answer regarding some recently published editions of classical authors.

Michael Neander is generally held as one of the greatest Protestant practical pedagogues of the sixteenth century and his textbooks are milestones in the history of primary education. Philip Melanchthon attested that the elementary school at Ilfeld was the best in the county. Neander was born at Sorau in the old Prussian province of Brandenburg, not far away from Frankfurt a.O. His father was a wealthy merchant, who intended him to continue his business. At the age of 18 he entered the Wittenberg University, where he listened with great enthusiasm to the lectures of Martin Luther, who became a close friend. In 1547, with a recommendation of Melanchthon and Justus Jonas, he obtained a position at the school of Nordhausen and in 1550 he changed for the school of the monastery of Ilfeld, the abbot of which, Thomas Stange, had converted to the Reformed faith and established an elementary school there. In the forty-five years that Neander acted there first as a teacher, and later as rector, the renown of the school increased from year to year. Lorenz Rhodomann, Neander's most famous pupil, said to his credit, that from his school at Ilfeld came out more Greeks then once heroes from the Trojan horse (cf. H. Heineck, Aus dem Leben Michael Neanders, Nordhausen, 1925, passim; see also M. Klemm, Michael Neander und seine Stellung im Unterrichtswesen des 16. Jahrhunderts, Grossenhain, 1884, passim).

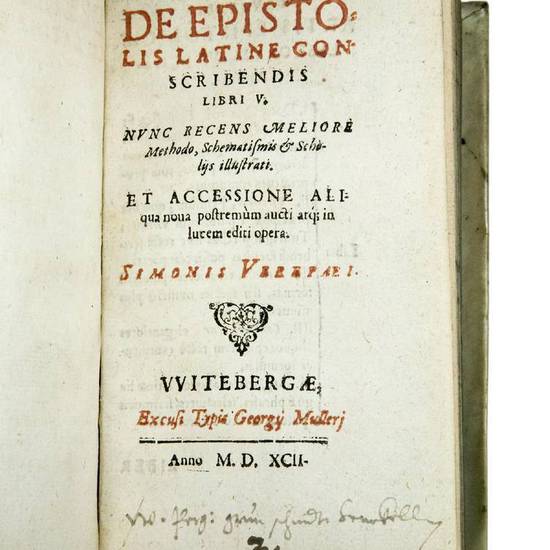

III. VEREPAEUS:

278 pp. A-R8, S4. Title printed in red and black with a typographical ornament. Contemporary vellum over boards, blind-stamped fillets on the panels with the lettering P.V.B 1597 on the front panel, old entries of ownership on the title-page. Ex libris Franz Pollak-Parnau.

Green & Murphy, p. 444; VD 16, V-603.

THIS EDITION is a literal reprint of that printed by Müller two years earlier. A first version in four books of Verepaeus' treatise on letter writing was first published at Antwerp in 1571. An augmented edition in five books was apparently first printed in 1580. Verepaeus charged Platin in Antwerp with the printing of a revised edition in 1588. The work was quite successful and had over twenty editions until the end of the century.

Verepaeus' tract “est une Ars epistolica basée sue les meilleurs auteurs latins. Les modèles donnent les noms de nombreux parents, amis, protecteurs et disciples de l'auteur ” (A. Gerlo, L' ‘Opus de conscribendis epistolis', in: “Colloquia Erasmiana Turoniensia”, I, 1971, p. 232).

“Verepaeus se préoccupe, à l'exemple d'Érasme, des thèmes des lettres que l'on proposera aux élèves; mais parmi les modernes, c'est Paul Manuce qu'il donne en exemple; il répartit les épîtres en dix-huit genres, tous classiques, sauf deux, et place en tête des qualités requises pour la lettre, la brevitas” (G. Gueudet, L'art de la lettre humaniste, Paris, 2004, p. 280).

That brevitas was one of the requisites of the epistolary style, was also emphasized by Jeroen Jansen in Brevitas, beschouwingen over de beknoptheid en stijl in de renaissance (Hilversum, 1995, I, p. 525): “Opvallend is dan wel dat Verepaeus ub zijn briefleer (De epistolis latine conscribendis, 1571) geen speciale nadruck op de brevitas legt, maar de drie kwaliteiten, latinitas, perspecuitas en ornatus aanbeveelt. Een verklaring hiervoor zou wellicht gevonden kunnen worden in het feit dat Verepaeus in deze gedegen briefleer, waarin bijvoorbeld tientallen openingsfrasen, afsluitingszinnen en een uitgebreide titulatur zijn te vinden, juist het tweede boek dat over de epistolaire stijl (De epistolari locutione) zou moetenhandelen, een algemener karakter heeft gegeven en hier meer over de virtutis elocutionis dan specifick over de ‘virtutes epistolae' spreekt”.

Verepaeus' manual was only printed once in England by Richard Field, a native of Stratford-upon-Avon, who is chiefly known as the printer of Shakespeare's Venus and Adonis (1594) and The Rape of Lucrece (1594), as well as various books of Shakespearean sources. It is likely that Shakespeare knew Field - they came from the same town and were just three years apart in age - and also Verepaeus' tract.

Simon Verepaeus, the great Belgian pedagogue, was born at Dommelen near Valkenswaard in Brabant. He made his first studies at Bois-le-Duc and then matriculated in the University of Louvain and obtained a degree in 1545. He became a teacher, first at the school of the chapter of Saint-Pierre-aux-Liens, then rector of the sisters of Mont Tabor at Malines and head of the Latin school of the chapter of Saint-Jean at Bois-le-Duc. Verepaeus wrote several treatises on Latin grammar, and some pedagogical and devotional works (cf. M.A. Nauwelaerts, Simon Verepaeus (1522-1598) paedagoog der contra-reformatie, Tilburg, 1950, passim).

At the end is furthermore found Lipsius' De recta pronunciatione latinae linguae dialogus [Antwerp, Plantin, 1596], which is usually found as an appendix to Lipsius' Opera omnia quae ad criticam proprie spectant (Antwerp, Plantin, 1596); it was first published in 1586 with a dedication to Sir Philip Sidney.

[9079]