A feminist novel

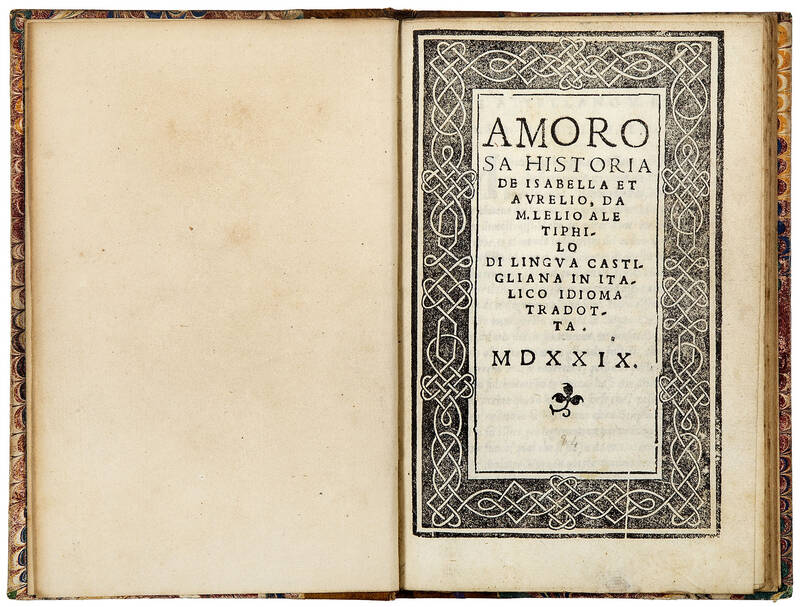

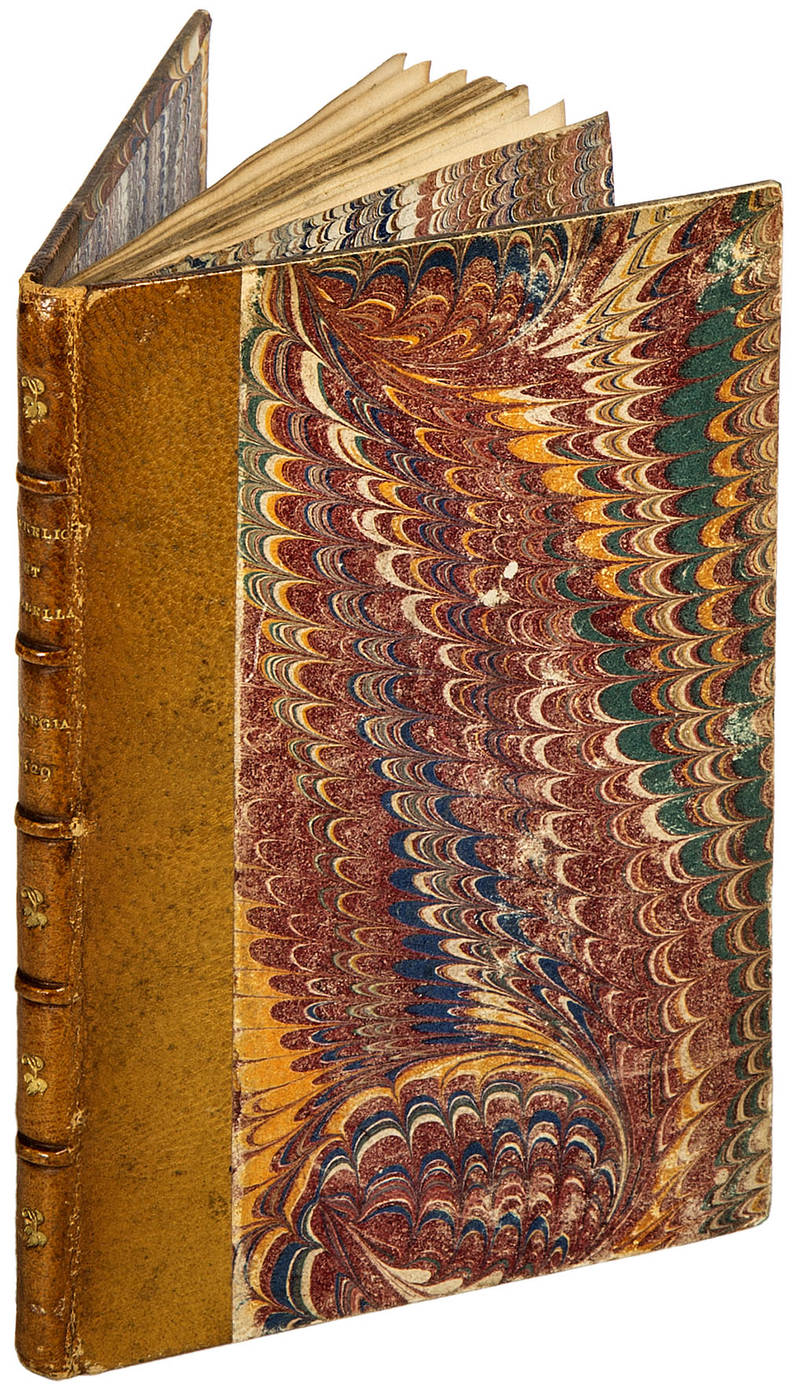

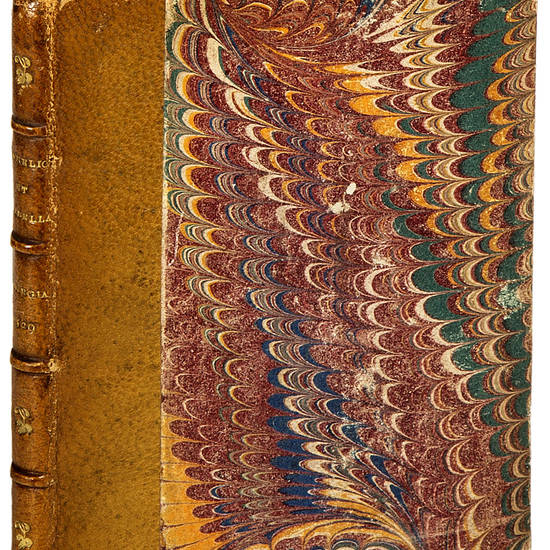

8vo (149x97 mm). [36] leaves. Collation: A-I4. Title within an elaborate geometric border on black ground. Italic type. Colophon on l. I4r. Leaf I4v is a blank. 19th-century half vellum, gilt spine with small raised bands, panels and endleaves in marbled papers. Small repairs to the last leaf affecting a few words of text skilfully supplied by hand. A nice copy.

RARE FOURTH EDITION of the Italian translation.

Juan de Flores was one of the most widely read Spanish authors in Europe before Cervantes. His fame is mainly linked to the story of Grisel y Mirabella, which, composed at the end of the fifteenth century and published for the first time in 1495, was reprinted about sixty times in various languages until the end of the sixteenth century. Together with the Cárcel de Amor and the Celestina, the novel by Flores represents the only other Spanish work of the time to have had a diffusion comparable to those of Orlando Furioso or Decamerone.

The novel, an important feminist document, was read especially by women and became a kind of manual for court instruction in modern languages. Through the narration of the tragic story of two lovers persecuted by a cruel fate and killed without mercy through inhumane laws, the novel vehemently entered the debate on gender and placed itself at the centre of the defence of woman's superiority. Starting with the debated issue of whether the pains of love are more readily inflicted by men or women, Flores goes on to address more general topics such as the equality of women before the law and their right to receive higher education.

The novel, which had a certain influence on such authors as Ariosto, Lope de Vega, and John Fletcher, tells the story of the beautiful daughter (Mirabella) of the King of Scotland, who loves her so much that he decides to lock her up in a tower and conceal her from the court knights, all of whom had fallen in love with her. Grisel, the only man able to make it to her, and the two fall in love. The two are found out and imprisoned, and the king decides to proceed with punishment according to a law whereby the most culpable party is put to death while the other is exiled. However, the two lovers refuse to accuse one another, even under torture. The king therefore orders a judicial debate with a representative of each gender: Braçayda and Torrellas are thus called, on behalf of women and men, respectively, to discuss whether, in affairs of love, men's responsibility is greater than women's. Despite the dialectical superiority shown by the female representative, the judges – all male – decide to blame Mirabella for the crime and condemn her to death. During the execution, however, Grisel saves her by throwing himself into the fire in her place. In despair, Mirabella soon throws herself out of a window. The queen, angry at the death of her daughter and the humiliation suffered by the champion of her sex, decides to take revenge on Torrellas. The latter, who has meanwhile fallen in love with Braçayda, is lured into a room of the royal palace by the fake complacency of the latter, attacked by a group of women, including the queen herself, and subsequently bound, tortured, and killed.

Among the many sources which inspired Flores, the story of Guiscardo and Sigismonda, narrated by Boccaccio in the Decameron, is the one that influenced him the most.

The European success of Flores's novel is mainly due not to its original Spanish version, but to the Italian translation attributed to a certain “Lelio Aletiphilo”. It was through the Italian version that the work was known and read, as well as translated into other European languages. Indeed, the German translator imitated his Italian colleague to the point of referring to himself as “Christian Pharemund”, a translation of “Aletiphilo”.

The most probable identification is that with the Mantuan man of letters Lelio Manfredi (d. 1528), who, on behalf of Isabella d'Este, Marchioness of Mantua, translated the Cárcel de Amor and Tirant lo Blanch (cf. C. Zilli, Notizia su Lelio Manfredi, letterato di corte, in: “Studi e problemi di critica testuale”, XXVII, 1983, pp. 39-54).

He offers his translation to Scipione Attellano, declaring in the dedication that he had strictly adhered to the original Castilian text, but had chosen to translate the original names: Torrellas becomes Afranio, Grisel Aurelio, Mirabella Isabella and Braçayda Hortensia. In reality, the translator took many liberties, correcting and integrating at his leisure. The Italian version, although less convincing than the Spanish one, became the most widespread, while the original soon fell into oblivion outside of Spain. In fact, rather surprisingly, the Spanish editions that later appeared outside the Iberian Peninsula are translations of the Italian remake.

Read for pleasure as well as a tool for learning modern languages, Flores's short story was reprinted several times after the first Italian edition (Milan, 1521). Multilanguage editions were also issued, presenting the text in two, three, and even four languages (French, Italian, Spanish, and English) (cf. B. Matulka, The Novels of Juan de Flores and Their European Diffusion. A Study in Comparative Literature, New York, 1931, pp. 5-237).

Little is known about the life of Juan de Flores. A native of Salamanca, he held several important positions, including those of historiographer of King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella and rector of the University of Salamanca. In addition to Grisel y Mirabella, he composed two other novels: Grimalte y Gradissa and Triunfo de Amor (see A. Pérez-Romero, The Subversive Tradition in the Spanish Renaissance Writing, Lewisburg, 2005, pp. 70-83).

Palau, no. 92500; Edit 16, CNCE42522.

[6799]