SHAKESPEARE'S SOURCES FOR OTHELLO AND MEASURE FOR MEASURE

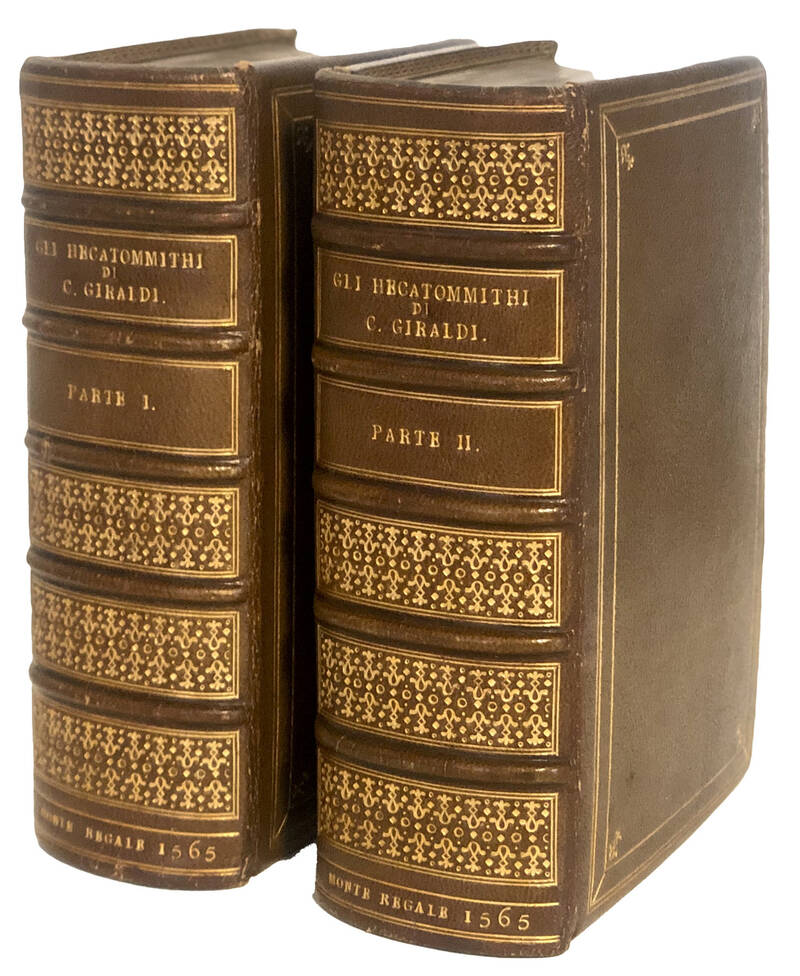

Two volumes, 8vo (162x98 mm). I: 14, [18], 1-199, [5], 201-326, [6], 329-486, [6], 489-623, [5], 625-751, [5], 753-902, [2] pp. Collation: [π]a8 *8 a-m8 n4 12 o-x8 22 y-hh8 32 ii-qq8 rr4 42 ss-bbb8 52 ccc-lll8 mmm4. Leaves *8, x8, 2/2, and hh8 are blank; II: [12], 1-63, [5], 65-208 pp., 209-224 leaves, [4], 217-317, [7], 321-368, [4], 369-490, [2], 493-623, [5], 625-798, [2], 799-820, [2], 821-822, [96] pp. Collation:**8 ***4 A-D8 [χ]E2 E-P8 62 [χ]P8 Q-V8 X4 72 Y-Aa8 82 Bb-Hh8 Ii4 Kk2 Ll-Ss8 Tt2 102 Vv8 X8 Yy-Ggg8 Hhh8 Iii4 a-e8 *8. Leaves *8 , ***4, 6/2, X4, Ggg8, and Iii4 are blank. Complete with all 10 blank leaves. With the printer's device on both title pages accompanied by the author's portrait on the verso of each. Bound in uniform full olive morocco tooled in gilt by J. Leight, aeg., marbled pastedowns with gilt dentelles. Some dedication leaves in the second volume extended, upper and outer margin occasionally cut short (on a few pages slightly touching the sidenotes), some occasional marginal staining and foxing, pages skillfully washed and pressed, some marginal paper repairs not affecting the text. A good copy.

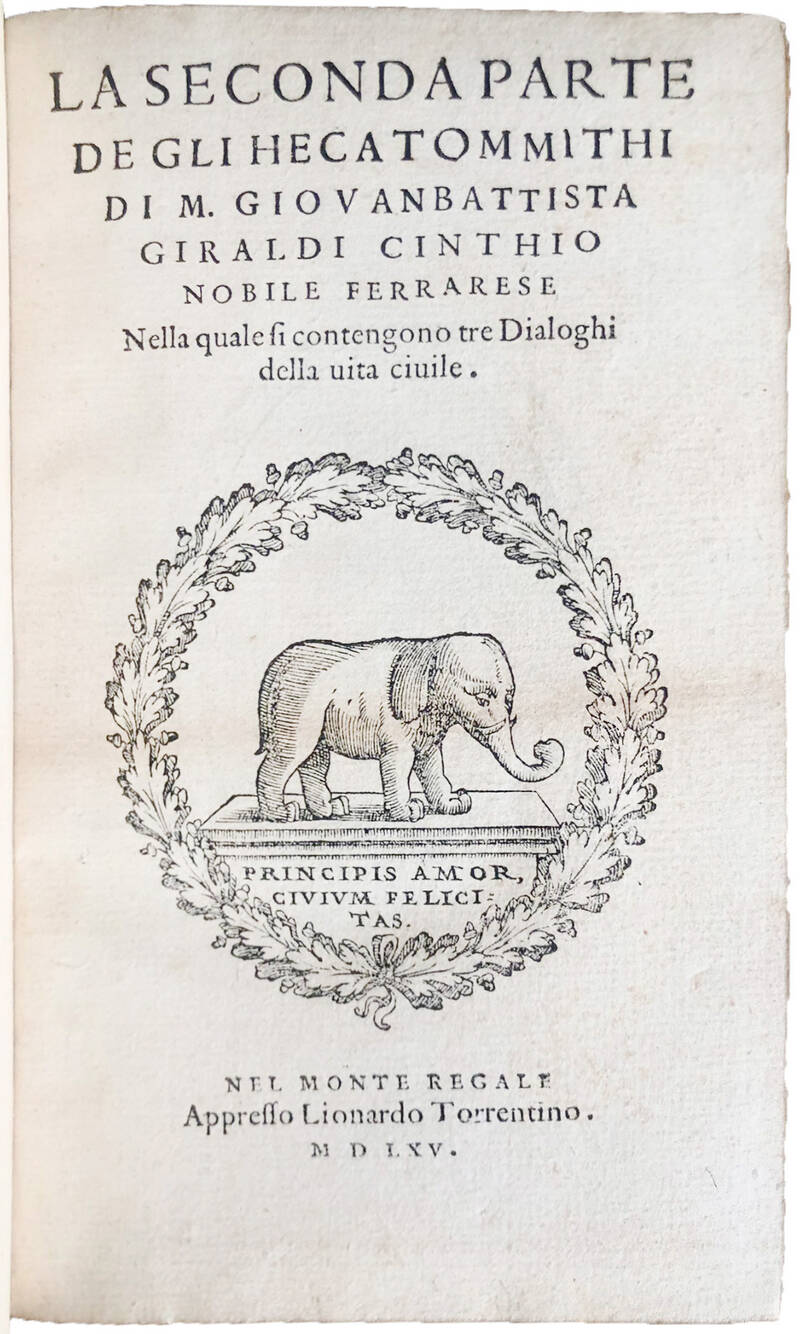

First edition, first issue, of this famous collection of tales. Divided into two parts, the Hecatommithi consists of one hundred and thirteen novellas organized across ten days, as well as poetic compositions, letters, dedications, and the Tre dialoghi dell'allevare et ammaestrare i figliuoli nella vita civile (‘Three Dialogues on Raising and Teaching Children in Civic Life'), written by Giraldi around 1550 and inserted into the middle of the collection, between the fifth and sixth days.

Giraldi began writing his novelle between 1527 and 1531. After a hiatus of nearly thirty years, he resumed his work when Emanuele Filiberto of Savoy, to whom the work is dedicated, called him to teach at the Mondovì University. An instant success, the work was reprinted numerous times until the end of the century and enjoyed broad dissemination across Spain, France, Germany, and England.

The year following the editio princeps, Giraldi published a new version at the presses of Girolamo Scotto (Venice, 1566), wherein, however, the final poem and the indexes are absent. Subsequent editions were also published in Venice, all posthumously: those by Enea de Alaris (1574), Fabio and Agostino Zoppini (1580 and 1584), Domenico Imberti, (1593) and Evangelista Deuchino (1608). To these must then be added French, Spanish, and German translations as well as numerous syllogies and imitations which appeared throughout Europe. However, none of these editions entirely adhere to the original structure conceived by Giraldi for the first edition of 1565: the Tre Dialoghi, in particular, are published separately from the corpus of the work, and almost all the paratexts surrounding the novellas are eliminated. After 1608, for over two centuries, Giraldi's novelle knew no other edition, possibly due in part to the Inquisition's prohibition, which placed the book on the Index of 1580.

Shakespeare's Othello derives from Giraldi's story of the “Moor of Venice” (cf. C. Azzolini, Giraldi, Chappuis e Shakespeare: la fonte e il testo dell' “Othello”, in: “Schifanoia”, 12, 1991, pp. 222-227), while novella 5, decade 8, is the source for the bard's Measure for Measure (cf. C. Roberts, The Politics of Persuasion: “Measure for Measure” and Cinthio's “Hecatommithi”, in: “Early Modern Literary Studies”, 7/3, (2002), pp. 1-17). Shakespeare presumably read Giraldi's Hecatommithi, as well as Ariosto's Orlando Furioso, in the original Italian version. “The source for Othello is Giraldi Cinthio's Hecatommithi. As the same collection contains a version of the story which provided the plot of Measure for Measure, and as that play written about the same time as Othello, Shakespeare was presumably scanning Cinthio's book in his search for plots in the early years of the 17th century […] In reading Cinthio's tale, he would have felt challenged by the magnitude of the difficulties involved in making a tragedy from it, but he would nevertheless have found several hints in the tale itself how the subject might be treated—the suggestion that Desdemona had fallen in love with the Moor's virtues and not from lust, her decision to brave the dangers of the sea, her later remark about mixed marriages, and the statement after the murder that the Moor loved her more than life” (K. Muris, The Sources of Shakespeare's Plays, London, 2005, pp. 3, 174, 182).

Other tales featured in the Hecatommithi also served as inspiration for various other literary works, including Beaumont and Fletcher's Custom of the Country, Whetstone's Promos and Cassandra, and seven of Giraldi's own plays: Orbecche (second novella of the second day), Altile (third novella of the second day), Antivalomeni (ninth novella of the second day), Selene (first novella of the fifth day), Euphemia (tenth novella of the eighth day), Epitia (fifth novella of the eighth day), and Arrenopia (first novella of the third day).

Similar to Boccaccio's Decameron, Giraldi's work contains a prologue set amidst the Sack of Rome in 1527, from which ten men and women escape by sailing to Marseille. To alleviate the monotony of the journey they tell each other a hundred tales (divided into ten decades). Published during a period of religious tension, Giraldi's Hecatommithi contains references to the moral edification readers may glean from his tales, which he contends uphold papal authority and the precepts of Christianity. Love within marriage, for example, is set forth as the only kind of earthly love able to bring about true happiness. Included in the work is a non-narrative section entitled Tre dialoghi della vita civile, comprising a three-day discussion on the active moral virtues required for civic life.

Giraldi's language was more intelligible to ordinary readers than the racy Tuscan of the Sienese authors and his stories had less of a purely local flavor than those of the Florentines. His narratives carry a weight and depth that mark him as a formidable literary figure. The variety of scenes he represents, the somber gravity of many of his motives, his intimate acquaintance with the manners and costumes of a class that never fails to captivate the masses, combined with his astute discernment in selecting and multiplying instances of sensational transgression, positioned him favorably with the particular audience for whom novelle were composed. Even when compared with Boccaccio, prince of storytellers, Giraldi holds his own, not as a great dramatic or descriptive writer, but as a keen observer who has studied, analyzed, dissected, and digested the material of human action and passion in a vast variety of modes. His work is more solid and reflective than Bandello's and more moralized than Il Lasca's. In spite, therefore, of the almost revolting frankness with which impurity, fraud, cruelty, violence, and bestial lust are exposed to view, one rises from the perusal of the Hecatommithi with an unimpaired consciousness of good and evil (cf. D. Maestri, Gli “Ecatommiti” del Giraldi Cinzio: una proposta di nuova lettura e interpretazione, in: “Lettere italiane”, 23/3, 1971, pp. 306-331).

“Al lungo Principio segue una altrettanto lunga Introduzione nella quale ‘si dimostra che, solo, fra gli amori umani è quiete in quello il quale è fra marito e moglie, e che ne' disonesti non può essere riposo'. L'Introduzione è composta da dieci novelle, è ‘condita' anch'essa da varie dediche (all'arcivescovo di Torino; a Tommaso Langusco, conte di Stroppina; a Luigi d'Este; a Laura Eustochia d'Este; a Cassiano dal Pozzo e a Margherita duchessa di Savoia) e ha come tema: ‘Gli amori disonesti de' giovani verso le femmine impudiche'. Si entra quindi nel vivo dell'opera con la Prima Deca, dove ‘si ragiona di quello che più ad ognuno è grado'. Nella Seconda Deca si ragiona invece di coloro che ‘o di nascosto o contra il voler de' maggiori hanno amato con fine lieto o infelice'. Nella Terza Deca si dibatte ‘dell'infedeltà dei mariti e delle mogliere', mentre nella Quarta e nella Quinta si narra rispettivamente di coloro ‘che pensando far guadagno col tendere ad altri insidie, giungono a fine degno delle loro malvagità' e poi ‘della fede dei mariti e delle mogli'. Qui finisce la prima parte dell'opera. La seconda parte si apre con i Tre Dialoghi dell'allevare et ammaestrare i figliuoli nella vita civile. I protagonisti di questa sorta di mini trattato sulle regole basilari da osservare nella società sono alcuni degli stessi narratori delle novelle (‘Fabio, Lelio et Torquato, gentiluomini romani' e ‘Giannettino d'Oria, nobile genovese'). Gli argomenti, lo si può immaginare, sono i più disparati e consistono soprattutto in consigli e modelli esemplari di comportamento (come la difesa della fortezza d'animo, dell'anima intellettiva secondo la lezione di Aristotele, e della bellezza come ‘cagione dell'amicizia', della giustizia, dell'equità o della prudenza) e nella ferma condanna dei vizi (‘abituarsi al male è sommo male'), nel tentativo – per citare Mario Pozzi – di ‘conciliare termini apparentemente antitetici come fortuna, provvidenza e libero arbitrio, con le moderne elaborazioni del pensiero cristiano, cattolico e controriformistico'. Terminata la lunga parentesi moraleggiante dei Tre Dialoghi, la seconda parte riprende quindi con le ultime cinque Deche: la Sesta, nella quale si parla ‘degli atti di cortesia', la Settima che racconta dei ‘vari motti e d'altri detti e risposte, subito usate per mordere e per rimordere o per schifare pericolo o vergogna' e le ultime tre (dall'Ottava alla Decima) che trattano ‘dell'ingratitudine', ‘della varietà degli avvenimenti umani e de' casi della fortuna' e infine, di ‘alcuni atti di cavalleria e di cose appartenenti a ciò'. Anche queste novelle hanno l'immancabile apparato dedicatorio (a Francesco d'Este; a Carlo Conte di Lucerna e governatore dello Studio di Monte Regale; a Lucio Paganucci, segretario di Alfonso II d'Este e ad Antonio Maria di Savoia, conte di Collegno), che raggiunge il top nelle ultime pagine del volume, con una sperticata celebrazione di Francesco I di Francia, potente interlocutore dei principi di Savoia e d'Este” (A. Ghisellini, Gli ‘Hecatommithi' di Giraldi Cinzio. La tormentata vicenda di un'opera, in: “La Biblioteca di via Senato”, Milan, February 2024, pp. 21-22).

“La presenza delle dediche negli Ecatommiti conferisce maggiore complessità ad una struttura decameroniana, già per se stessa capace di garantire un'organica classificazione di temi ed argomenti. In realtà, servendosi delle dediche, l'autore poteva fornire al lettore un'importante ed autorevole chiave di lettura, enucleare i concetti ed i temi fondamentali di ciascuna deca, indicare i più importanti punti di forza e di contatto […] La complessa struttura degli Ecatommiti accoglie anche un lungo capitolo in terzine, intitolato “L'Autore all'opera”, che costituisce la parte finale della raccolta ed è introdotto da una presentazione dell'editore fiammingo Arlenio Arnoldo. Composto ad imitazione del XLVI canto dell'Orlando Furioso, il capitolo riveste una certa importanza storica, in quanto l'autore, fingendo un dialogo immaginario con la propria opera, tesse sommarie lodi di un numero cospicuo di personaggi del tempo” (S. Villari, Per l'edizione critica degli Ecatommiti, Messina, 1988, pp. 31-32).

This final chapter of volume two -the author in conversation with his work, L'autore all'opera- was corrected and expanded by Giraldi during the printing process, leading to two extant versions of the text. The present copy contains the first, shorter version, spanning eight leaves, on pp. 799-814 (quire Hhh). To accommodate the second, longer version, quire Hhh was entirely reset and four leaves (numbered 815-820) were added at the end.

Giovanni Battista Giraldi was born in Ferrara and educated at the university of his native town, where he became professor of natural philosophy in 1525 and where, twelve years later, he succeeded Celio Calcagnini in the chair of belles-lettres. Between 1542 and 1560, he served as private secretary, first to Ercole II and afterwards to Alfonso d'Este, whose favour he ultimately lost due to his (Giraldi's) involvement in a literary quarrel. He then moved to Mondovi, where he remained as a teacher of literature until 1568. Upon the invitation of the senate of Milan, he subsequently assumed the chair of rhetoric at Pavia, a position he held until 1573. That year he returned to his native town in an attempt to improve his health but passed away on December 30.

Apart from the Hecatommithi, his most significant collection, Giraldi authored a disquisition on the methods to be observed in the composition of epic, romance, and drama (1554), which shows him to be one of the leading literary critics of the time. He ventured into pastoral drama with the Eagle (1543), and the epic genre with the Creole (1557). His dramatic endeavours extended to the creation of one comedy, Eudemoni, and nine tragedies, including Didone, Cleopatra, Selene, as well as his highly acclaimed Orbecche, the first original tragedy in classical style to be staged in Italy, in 1541. (cf. P. Cherchi, M. Rinaldi & M. Tempera, eds., Giovan Battista Giraldi Cinzio gentiluomo ferrarese, Florence, 2008, passim).

In Mondovì, then an affluent city renowned for its paper production, the first printing press was established in Piedmont, in 1472. Printing operations came to a halt, however, in 1521, due to the war between the king of France, Francis I, and the duke of Savoy, and subsequently resumed only in 1564, with Leonardo Torrentino. Torrentino's father, Lorenzo, who had served as the ducal printer to the Medici in Florence for an extended period, had been summoned to Mondovì in 1561 by Emanuel Philibert of Savoy. The duke had recently founded a new university in Mondovì and required a press for it. Lorenzo died only a few months after his arrival, without any opportunity to commence printing. It thus fell upon his son, Leonardo, to assume responsibility for the business. With the assistance of the humanist Arnoldus Arleius, a longtime associate of Lorenzo, he successfully printed over thirty titles within a span of three years. Leonardo's activity was cut short with his untimely death in 1566. (cf. C. Duroselle-Melish, Lorenzo Torrentino, a Mondovian Printer (1564-1566), in: “The Library Quarterly: Information, Community, Policy”, vol. 83, no. 2, April 2013, pp. 152-154).

Edit 16; CNCE21271; Adams, G-704; G. Passano, I Novellieri italiani in prosa, Turin,1878, I, pp. 352-354; G.B. Giraldi, Gli Ecatommiti, S. Villari, ed., Rome, 2012.

[12999]