“A TRUE RESURRECTION OF ROMAN COMEDY” (HERRICK)

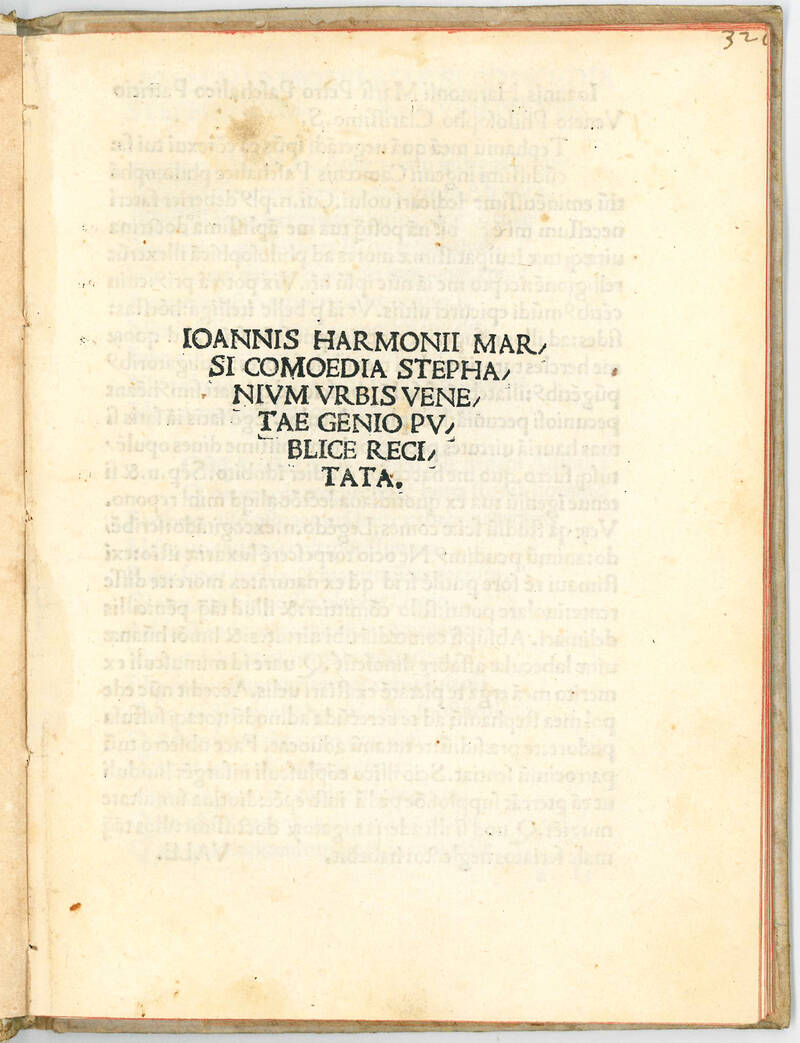

4to (202x149 mm). [22] leaves. Collation: a-e4 f2. Woodcut initial on black ground. Later flexible vellum, red edges. Small restorations to the last leaf slightly affecting the text, all in all a very good, fresh copy.

Extremely rare first edition of this Latin comedy in iambic senaries first performed around 1500 in the courtyard of the convent of the Eremitani in Venice. The author, a twenty-three-year-old friar from Abruzzo who in 1516 became organist at the Chapel of San Marco, played a part himself on stage. In the audience was seated Marco Antonio Sabellico (c. 1436-1506), the great humanist and historian, who like all the other attending people greeted the comedy with great enthusiasm. At the end of the volume are a few encomiastic pieces in verse and prose by Sabellico himself, Giovanni Battista Scita (d. 1515), Paolo da Canale (1483-1508), Girolamo Amaseo (1467-1517), and Frater Jacopus Baptista (cf. I. Sanesi, La commedia, Milan, 1954, I, p. 124).

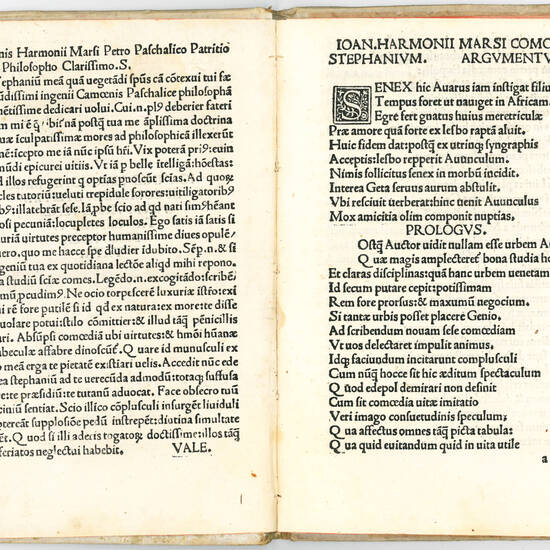

The edition is dedicated by the author to Pietro Pasqualigo (1472-1515), a Venetian patrician who had studied philosophy and theology in Paris and spent many years of his life as Venetian ambassador in Portugal, Spain, England, Hungary, France, and at the emperor's court.

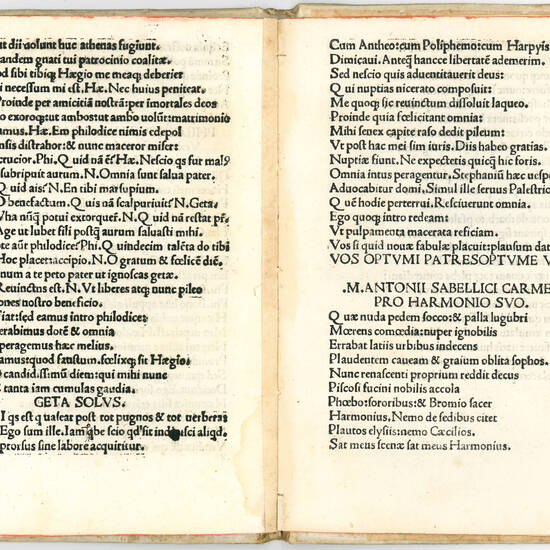

“Giovanni Armonio Marso wrote a comedy called Stephanium which aroused much enthusiasm in learned circles when it was produced about 1500. This play seemed to be a true resurrection of Roman comedy: it was in Latin verse, its characters (young lover, miserly father, cunning servant, a young girl who never appears on stage, and a cook) were reminiscent of Roman practice, and its argument was reminiscent of Plautus. The author was certainly trying to emulate classical comedy. The prologue speaks of the paly as a “new comedy” (nova comoedia). Now the word ‘new' could have two meanings in 1500; it could mean new in the sense of never seen before or new in the sense that it was like the New Comedy of ancient Greece and Rome and unlike the native medieval drama. The prologue quotes the Ciceronian definition of comedy as transmitted by the Terentian commentator Donatus: ‘an imitation of life, a mirror of custom, an image of truth'. Furthermore, it sketches the history of comedy from Eupolis and Aristophanes, to Menander, Plautus, and Terence, that is, to the New Comedy. There is a reason to believe that Marso also owed a debt to another humanistic comedy, the Epirota of Thomas Medius. The plot of Stephanium is a rather simple love story. Niceratus of Athens has fallen in love with Stephanium of Lesbos and has promised to marry her. The girl, however, is homeless and penniless and would never be acceptable to the young man's father, who wants to send his son to Africa where he may learn the merchant's trade. Niceratus has put off his departure from day to day until his father suddenly falls ill. Then Geta, the servant in league with the young master, steals the old man's gold. At the beginning of the last act, Stephanium's uncle, Philodocus, arrives in Athens on the trail of his lost niece. He soon encounters Niceratus [and the two find out that Philodocus is a close friend of Niceratus' father]. Philodocus explains that he is hoping to find his niece and a good husband for her. He adds that she will have a large dowry. All the difficulties facing the lovers now vanish and a happy ending is assured” (M.T. Herrick, Italian comedy in the Renaissance, Urbana and London, 1966, pp. 20-21).

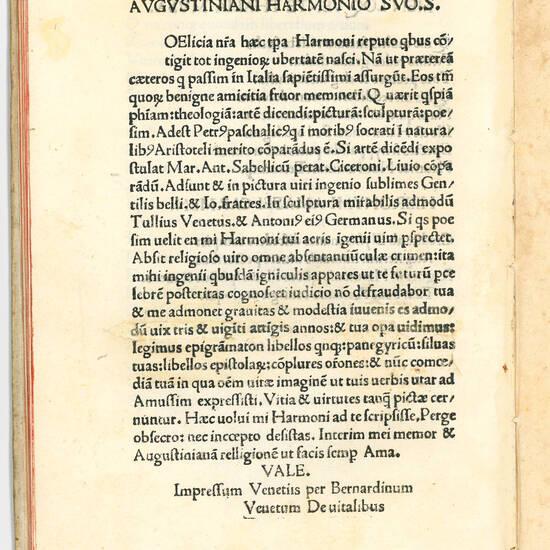

Armonio's comedy is one of the first plays ever staged in Venice, preceding by eight years the first performance of a drama by an ancient author, which, according to all major sources, dates back to 1508. In Sabellico' Opera, published in Venice in 1502, at p. 52 there is a letter addressed by him to Marco Armonio. In the letter, Sabellico, who had the chance to read the comedy before it was published and had attended firsthand its first staging, praises the work for the ‘argumentum, dignitas personarum, sententiarum gravitas, verba cum vetusta, tum figura et lepore Plautinis simillima”, using a terminology that is clearly taken from Aristotle's Poetics, whose first edition had appeared in Venice only a few years earlier (1498) in Lorenzo Valla's Latin translation. Sabellico also wrote a short poem in praise of the work and its author (compared to a new Plautus), which Armonio decided to include in the printed edition as the first of the encomiastic texts published at the end of the volume. The eulogies and the comparison with Plautus, Terentius, and Naevius (of whom Armonio is considered a reincarnation) are carried forward also in the following poems by Paolo da Canale and Girolamo Amaseo. The volumes finally closes with a prose letter to Armonio by the Agostinian father Jacopus Baptista from Ravenna, in which Armonio's other works, i.e., epigrammaton libelli, a panegyricus, a book of Silvae, libelli epistolarum, and orations, are listed. Jacobus Baptista also puts Armonio for his revival of ancient drama at the same cultural level of the dedicatee of the edition Pietro Pasqualigo who is compared to Socrates and Aristotle, of Marco Antonio Sabellico compared to Cicero and Livy, of the Venetian master painters Gentile and Giovanni Bellini, and of the sculptors Tullio and Antonio Lombardo.

The Stephanium had a certain success also north of the Alps, especially in the circle of the Viennese humanists; it was in fact reprinted in Vienna by Hieronymus Vietor in 1515 and 1517. It was still read around the mid-century as attested by Lilio Gregorio Giraldi, who mentions it in his De poetis nostrorum temporum (1551) as one of the few modern dramas that stands the comparison with those of the ancient playwrights.

Not only Sabellico's account, but also the structure itself of the comedy clearly demonstrate that Armonio conceived the Stephanium for an actual staging. We know that he also played as an actor in it, but we don't know what part he chose for himself; maybe that of Geta, who is on stage more than any other character and clarifies the moral meaning of the play when he says: “pater avarus, filius prodigus, nihil est medii” (v. 398) (cf. W. Ludwig, Einleitung, in: G. Armonio, “Ioannis Harmonii Marsi Comoedia Stephanium”, Munich, 1971, pp. 9-87).

BMSTC Italian, 1465-1600, p. 323; Brunet, III, 1474; Edit 16, CNCE3064.

[12705]