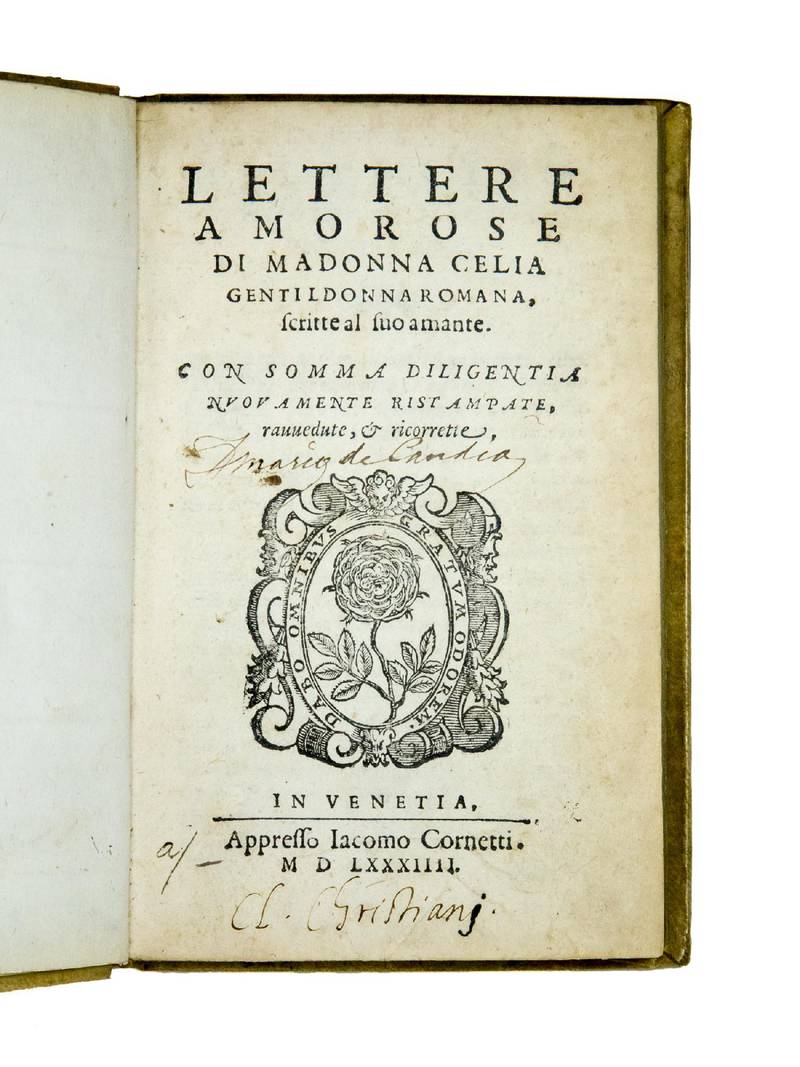

8vo. 76 leaves. A-I8, K4. With the printer's device on the title-page. Printed in italic. Eighteenth-century vellum over boards, lettering piece on spine, marbled edges. Ownership entries on the title page including "Mario de Candia", possibly the great Sardinian tenor with the same name (1810-1883).

Adams, P-506 (attributed to Girolamo Parabosco); Basso, p. 208; Edit 16, CNCE 10730; Quondam, pp. 111-112 and 294; M.L. Doglio, Lettera e donna: Scrittura epistolare al femminile tra Quattro e Cinquecento, (Roma, 1993), p. 34; A. Erdmann, My Gracious Silence, (Luzern, 1999), p. 210; R. Russell, The Feminist Encyclopedia of Italian Literature, (Westport, CT, 1997), p. 295.

FIFTH EDITION of this collection of sixty-eight fictitious love letters signed by Madonna Celia under her name or the pseudonym of Zima. First published in Venice by Antonio degli Antonii for Francesco Rampazzetto in 1562, it was reprinted 10 times until 1628.

Towards the end of the century the book was put in the Index as all the works related to profane love, and therefore could be printed only donec expurgetur. “Lo stesso [Fabrizio] Zanetti ripubblicò nel 1600 le Lettere amorose di Madonna Celia Romana, con numerose variazioni rispetto alla prima edizione del 1562: veniva soppressa la dedica dell' ‘Amante alla Signora Lisa', sostituita con una lettera dedicatoria firmata dallo stesso Zanetti a Ottavio Sfoglio, ‘gentiluomo trevigiano'. In un avviso ai lettori, lo stampatore giustificava la sua operazione con il fatto che la raccolta da molti anni non aveva avuto riedizioni, eccetto alcune ‘mal corrette'. Anche in questo caso numerosi erano gli interventi sul testo: in modo particolare l'espurgatore eliminava tutti i termini religiosi usati per esprimere la passione amorosa […]” (L. Braida, Libri di lettere. Le raccolte epistolari del Cinquecento tra inquietudini religiose e “buon volgare”, Bari, 2009, pp. 284-285).

The letters are all addressed by Celia to her anonymous lover, who is also the editor of the collection. In the dedication to Signora Lisa, he says that from the thousand letters he had received in the fifteen-year-long love affair with Celia, he had decided to select some of them in order to warn all men and all women against the dangers of love, and to demonstrate the intellectual and human qualities of Celia which, despite she had not received a proper education, leaked clearly even from her hasty letters. Most of the letters are dated. The earliest date is February 2, 1549; the latest December 30, 1560.

“As the sixteenth century progressed, early modern writers continue to capitalize on the converging trends of epistolary literature and widespread interest in describing the female experience, turning increasingly to manuals and repertories for guidance. On the one hand, popular epistolary narratives such as the Lettere amorose of Madonna Celia and those of Girolamo Parabosco began to codify representations of the woman writer as an epistolary character motivated by passion and lovesickness. Models for such fictionalized and generalized female narrators, who fell from grace as they abandoned the feminine ideals of chastity and silence to follow their hearts, abounded” (M.K. Ray, Writing Gender in Women's Letter Collections of the Italian Renaissance, Toronto, 2009, p. 123).

“The genre, and the pseudonymous publication, would lead us to suspect that the author was a fictional creation, though the fact that a sonnet by a Celia Romana appears in a verse collection of the period (Tempio, 1568, l. 31v) leaves open the possibility that she may have existed” (V. Cox, Women's Writing in Italy 1400-1650, Baltimore, MD, 2008, p. 317, no. 5).

[9133]