A UTOPIAN-REVOLUTIONARY CONSTITUTION

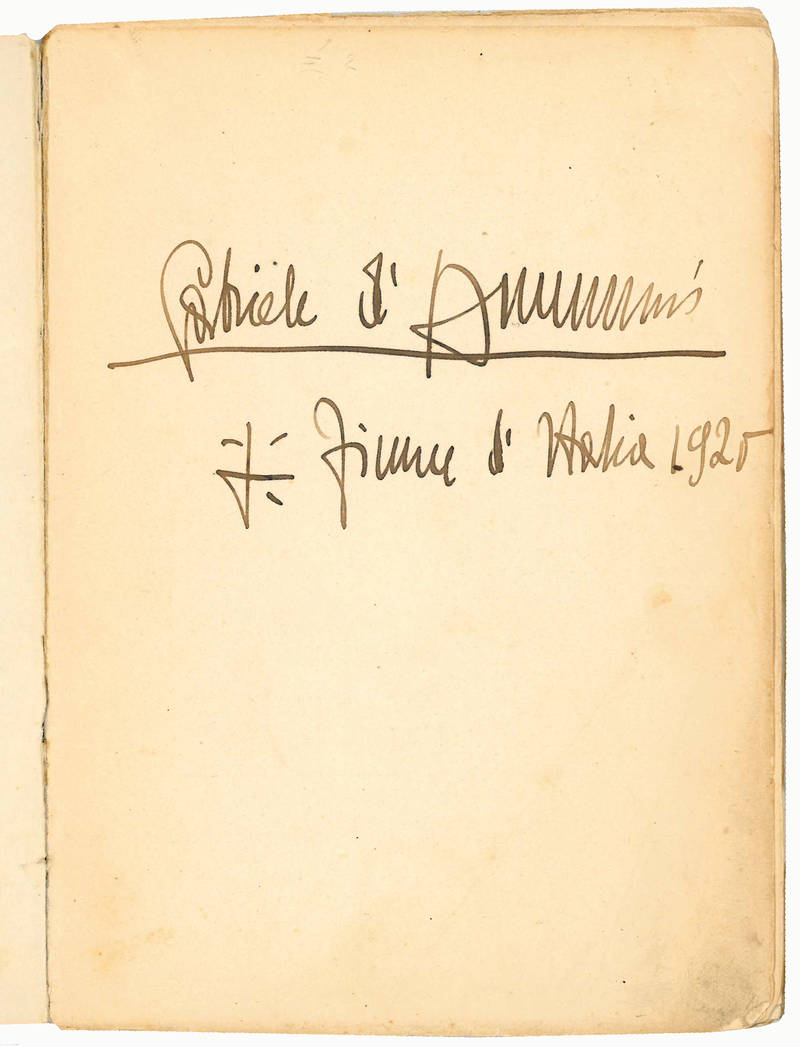

16mo (196x140 mm). 70, [2] pp. Editor's printed wrappers (slightly worn). At pp. 21, 38 and 39 the word “Repubblica” has not been replaced with the word “Reggenza” as in later issues. Signed by the author on the front flyleaf recto: “Gabriele d'Annunzio Fiume d'Italia 1920”. Some quires loose. A very good full-margined copy, partly still unopened.

First edition, printed in one hundred and ten non-commercial copies, of the full text of the “Carta del Carnaro”, a visionary constitution combining the sociological and political insights of Gabriele D'Annunzio with the revolutionary spirit of Alceste De Ambris. The present volume is in the first issue, in which the word “Repubblica” (‘Republic') has not yet been replaced for political reasons with the word “Reggenza” (‘Regency'). The word “Repubblica” still appears on August 31 in the Fiume newspaper “Vedetta d'Italia” and on September 1 in the “Popolo d'Italia”, but is corrected in the official version published, likewise on September 1, in the “Bollettino ufficiale del Comando di Fiume d'Italia” (‘Official Bulletin of the Fiume Command of Italy').

Presented publicly by D'Annunzio at the Fenice Theater on August 30, the extremely modern republican “Carta del Carnaro” became the constitution of the free town of Fiume. It was written by De Ambris and D'Annunzio in the hope of extending to all of Italy the movement of clear revolutionary and republican inspiration that was taking shape in Fiume.

After World War I Fiume, today Rijeka in Croatia, was disputed between the Kingdom of Italy and the newly born state of Yugoslavia. It was conquered by rebel units of the Italian army, known as D'Annunzio's 1,000 “legionaries”, on September 12, 1919, during the march from Ronchi (a small town near Gorizia), with the intention of proclaiming the annexation of the city to Italy and thus forcing the hand of the delegates then in attendance at the Paris peace conference. The expedition was led by the poet and novelist Gabriele D'Annunzio and organized by a political coalition headed by the Italian Nationalist Association (Associazione Nazionalista Italiana), with the participation of Futurists and revolutionary syndicalists. De Ambris joined D'Annunzio in Fiume in January 1920.

The new constitution, divided into sixty-five articles, went into effect on September 8, 1920, and transformed the Istrian city of Rijeka and surrounding territories - soon to be annexed to Italy in the hope of D'Annunzio - into a temporary regency and a sort of free city-state. The text of the charter is based on a draft prepared by the Fiume command's chief of staff, the anarchist and syndicalist Alceste De Ambris, and rendered into poetic form by D'Annunzio. The result is a unique example of a constitution in free verse. In particular, D'Annunzio transformed De Ambris's text into art prose with the systematic use of archaic terms taken from the language of ancient municipal and corporate statutes to designate modern institutions and magistratures.

The new statute enshrined a decentralized democratic republic, in which the implementation of laws was entrusted to seven rectors. At the top of the system was the figure of the commander, who could assume dictatorial powers only in cases of extreme danger. The “Carta del Carnaro” also assigned a leadership role to labor organizations, extended universal suffrage to women, introduced divorce, made military service mandatory for both men and women, established a Free University and public schools of fine arts, decorative arts, and music, to whose importance in public life an entire article is dedicated.

The adventure ended shortly thereafter. With the Treaty of Rapallo of November 20, 1920, Fiume was declared a free city, and on December 26 of the same year the new Italian government headed by Giovanni Giolitti forced D'Annunzio and his followers to evacuate the city.

In the “Carta del Carnaro” D'Annunzio infused his poetic taste and progressive thinking into creative and innovative constitutional norms of explicitly republican faith. Although it had an ephemeral life, the charter stands as a legal monument of decidedly progressive and libertarian content, much of which would be incorporated many decades later into the constitutions of modern democracies.

The “Carta del Carnaro” also had a wide international resonance. In October 1920, at the Congress of the Third Communist International, Lenin called D'Annunzio the only true Italian revolutionary. Not surprisingly, Soviet Russia was the only state to recognize the Free State of Fiume. The “Carta del Carnaro” can thus rightly be considered a revolutionary document for its time and it is hard to overlook the political modernity with which private property, labor relations, public education with a multilingual approach, the status of women, administrative decentralization and the revocability of political mandates are in it defined.

Gabriele D'Annunzio, a native of Pescara, demonstrated a very precocious aptitude for literature and self-promotion. In 1879 he published, at his father's expense, his first work, Primo vere, a collection of poems that was quite successful, thanks in part to the expedient devised by D'Annunzio himself of spreading false news of his own death.

He moved to Rome in 1881, following his high school studies, where he already enjoyed a certain notoriety. He stayed there for ten years, writing journalistic accounts and publishing, in 1889, his first novel, Il piacere, whose protagonist leads a flamboyant and luxurious life much like that of the author.

D'Annunzio later lived in Naples, where he composed the novels L'innocente and Il trionfo della morte and the lyrics of the Poema paradisiaco. In 1897 he moved to the villa “La Capponcina” in Settignano to live next door to the famous actress Eleonora Duse, with whom he was having an affair. In 1904 he broke with Duse and published Il fuoco. In 1910, to escape debts, he left for France, where he was already a well-known figure thanks to the translation of his works. During his French sojourn he composed opera librettos for P. Mascagni and C. Débussy.

At the outbreak of the World War I, D'Annunzio enlisted as a volunteer and severely injured an eye in a plane crash. During his convalescence he wrote Notturno, later published in 1921. In 1918 he took part in the famous bravado flight over Vienna. After the Fiume experience he retired to his villa on Lake Garda known as the “Vittoriale degli Italiani”, where he worked and lived until his death.

Despite his apparent celebration of the fascist regime, the relations between D'Annunzio and Mussolini were never truly cordial. On the contrary, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, the founder of Futurism, gradually changed his attitude towards D'Annunzio from blame to unconditional praise. Whereas in his first Futurist manifestoes (1909-1915) Marinetti considered D'Annunzio as a symbol of passatism, this hostile attitude changed with the Great War and with the seize of Fiume, and after these events Marinetti increasingly represented D'Annunzio as a Futurist man and writer.

M. Guabello, Raccolta dannunziana, Biella, 1948, p. 291; C. Salaris, Alla festa della rivoluzione: artisti e libertari con d'Annunzio a Fiume,Bologna, 2019, pp. 86-88; F.C. Simonelli, D'Annunzio e il mito di Fiume. Riti, simboli, narrazioni, Ospedaletto, 2021, pp. 134-181; R. De Felice, La Carta del Carnaro nei testi di Alceste De Ambris e di Gabriele D'Annunzio, Bologna, 1974.

[12067]