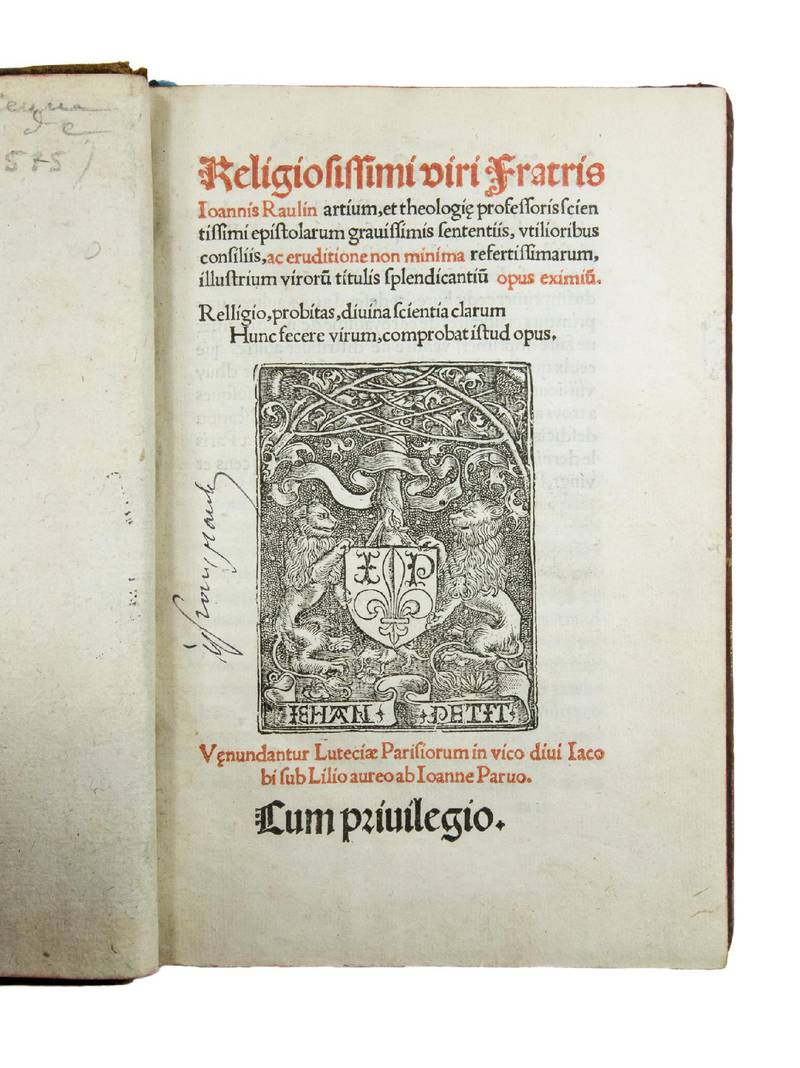

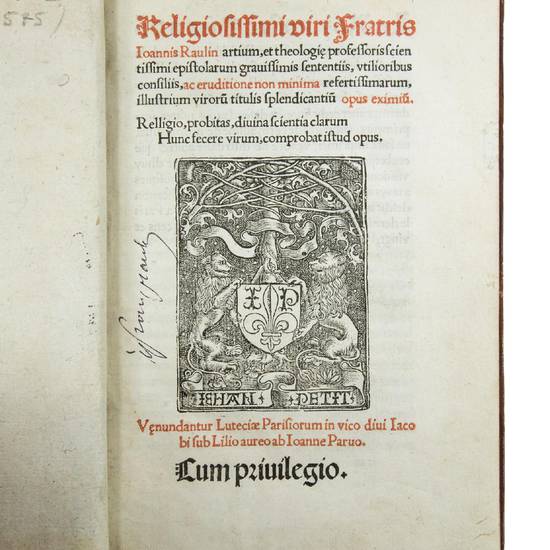

4to. (8), clxvi, (i.e. clxx), (1) leaves (with errors in the foliation). aa4, bb4, a-q4/8, r-s4, t-v8, x4, y8, z8, &8, 94, A8, B4, C4, D8 (-D8 blank). Title printed in red and black with the printer's device. Eighteenth century marbled calf, gilt spine with five raised bands, red morocco label, red edges, marbled endpapers.

Adams, R-182; G. Guedet, L'art de la lettre humaniste, (Paris, 2004), p. 299; B. Moreau, Inventaire chronologique des éditions parisiennes du 16e siècle, (Paris, 1985), III, p. 149, no. 391.

FIRST EDITION of this collection of 56 letters published by the author's nephew Robert Raulin. “On trouve, dans la correspondence de Raulin, la même doctrine de réforme par le retour aux vertus monastiques: chasteté du corps, ‘abstinence' de l'esprit, devotion, paix et concorde, obéissance ou plus simplement ‘la pauvreté et la charité' ” (G.T. Bedouelle, Jean Raulin, in: “Dictionaire de Spiritualité”, Paris, 1932-1995, 13, pp. 156). These ideas are clearly expressed in the letter to the friars of St. Alban in Basel (ll. LVv-LIXr).

“Several ideas may be drawn from his correspondence. First, Raulin relied heavily upon his long term relationships in the clerical milieu, bishops and heads of monasteries, to push his reform efforts forward. He labored primarily with and among the Benedictines, with a few exceptions, and crossed into other monastic orders only as the need arose. Second, many of Raulin's correspondents were relationships that he had developed during his time as chancellor of Navarre; many were former colleagues and students. It is possible that Raulin had begun to sow the seeds of clerical reform among colleagues and students while at Navarre. Later, as his ideas matured and his plan unfolded, those relationships proved useful and strategic for clerical reform. A third idea we can draw from his correspondence is that he appears to have had a precise strategy - he wrote those in positions of leadership who might more successfully accomplish reform in the monasteries. The majority of his letters are addressed to those in ecclesiastical authority, bishops, abbots, and priors, who had greater authority to bring reform to the monasteries. Fourth, his reliance on political help to accomplish reform was minimal, although he did use civil authority to force entry into a few monasteries and to impose his reforms. Fifth, the College of Navarre was a center of reformist and humanist activity since the time of Gerson, early in the fifteenth century. Twenty-five letters of the fifty-six were addressed to former Navarrists, nine former graduates and professors of Navarre during the twenty-five plus years that Raulin was associated with the school. Eight letters were addressed to the like-minded principle of the College of Montaigu and close friend, Jean Standonck, who was also involved in clerical reform. A sixth idea is seen in the nature of Raulin's letters. They fall into three main categories: 1) letters of encouragement to continue in the struggle for reform; 2) letters of admonishment to those who were not taking an active enough of approach in the reform; and 3) letters asking for help or influence to push the reform forward. Based on the existing correspondence, clerical reform, both monastic and episcopal reform was the central theme in Raulin's Epistolae” (H.K. Foreman, Jean Raulin, 1443-1515, and the ‘Ideal Clergy': a Study of Clerical Reform in Early Sixteenth Century France, Thesis, Aberdeen, 2008, pp. 69-70).

Added is a speech Raulin held at the Collège de Navarre and the famous oration on church reform held in the monastery of Cluny, Collatio de perfecta religionis plantatione, incremento, et instauratione, published for the first time at Basel by Sebastian Brant in 1498. At the end is found a poem by Nicolas Barthélémy de Loches and one by Sebastian Brant.

Epistola liminaris. Raulin, Robert to Selve, Jean de (l. aa2r)

Poncher, Étienne (l. Iv)

[Amboise, Louis d'], Bishop of Albi (l. IVv)

id. (l. Ixr)

id. (l. XIIIIr)

id. (l. XVv)

Standonck, Jean (l. XVIIIv)

id. (l. XXIIIIr)

id. (l. XXIXv)

Galle, Louis (Louis XII?) (l. XXXIIIIr, i.e. XXXIIIr)

Pinelle, Louis (l. XXXVIIIv)

Amboise, Jacques d' (l. XXXVIIIv, i.e. XLIv)

Potier, Denis (l. XLIr, i.e. XLIIIIr)

Pinelle, Louis (l. XLIIr, i.e. XLVr)

[Paris], Jérôme, prieur de Fontevraud (l. XLIIIr, i.e. XLVIr)

[Utenheim, Christoph von?], Custos Ecclesiae Basiliensis. Cluny, July 13, n.y. (l. XLVIv, i.e. ILv)

id. (l. LIIr, i.e. LVr)

Fratres Sancti Albani Basiliensis (l. LVv, i.e LVIIIv)

[Amboise, Madelaine d'], Abbatissa Sancti Menulphi (abbess of Saint-Menoux) (l. LIXr, i.e. LXIIr)

[Rochechouart, Marie de?], Abbatissa de Carentonio (l. LXIv, i.e. LXIIIIv)

[Lamps, Jean II de], Abbas Sancti Michaelis (abbot of Saint-Michel, composed by Pierre Pouchin) (l. LXIIv, i.e. XLVv)

Lantmann, Johannes (l. LXVIr, i.e. LXIXr)

[Utenheim, Christoph von], Custos Ecclesiae Basiliensis (l. LXVIIIr, i.e. LXXIr)

Id. (l. LXIXr, i.e. LXXIIr)

Blancbaston, Jean (l. LXXr, i.e. LXXIIIIr)

Fournes, Jean de (l. LXXv, i.e. LXXIIIIv)

Pinelle, Louis (l. LXXIIv, i.e. LXXVIv)

id. (l. LXXIIIr, i.e. LXXVIIr)

Blois, Jean de (l. LXXVIIv, i.e. LXXXIv)

[Jouenneaux, Guy], Abbas Sancti Sulpicii Bituricensis (Abbot of Saint-Sulpice de Bourges) (l. LXXXr, i.e. LXXXIVr)

Standonck, Jean (l. LXXXIv, i.e. LXXXVv)

[Bourgoing, Philippe] Ad priorem claustralem (l. LXXXIIr, i.e. LXXXVIr)

Potier, Nicolas (l. LXXXIIIr, i.e. LXXXVIIr)

Standonck, Jean (l. LXXXVIv, i.e. XCv)

Pinelle, Louis (l. XCIIr, i.e. XCVIr)

Varambon, Jean (l. XCIIIIv, i.e. XCVIIIv)

[Blésis, Jean de], Archidiaconus Bituricense (Archdeacon of Bourges) (l. XCVv, i.e. ICv)

Id. (l. XCVIIIr, i.e. CIIr)

[Utenheim, Christoph von], Custos Sancti Albani (l. XCVIIIv, i.e. CIIv)

Blancbaston, Jean (l. CIIIv, i.e. CVIIv)

[Dufour, Antoine?] Ad confessorem regium (l. CIIIIv, i.e CVIIIv)

[Blésis, Jean de], Archidiaconus Blesensis (Archdeacon of Blois) (l. CVIIIv, i.e. CXIIv)

[Rély, Jean de], Episcopus Andegavensis (Bishop of Angers) (l. CIXr, i.e. CXIIIr)

Picard, [Jean] (l. CXIr, i.e. CXVr)

Standonck, Jean (l. CXIIIIr, i.e. CXVIIIr)

Blancbaston, Jean (l. CXVr, i.e. CXIXr)

id. (l. CXVIr, i.e. CXXr)

[Blésis, Jean de] Archidiaconus Bituricense (Archdeacon of Bourges) (l. CXVIIIv, i.e CXXIIv)

id. (l. CXXr, i.e. CXXIIIIr)

Bourgoing, Philippe (l. CXXv, i.e. CXXIIIIv)

Ad Celsinarum patrem (l. CXXIIv, i.e. CXXVIv)

Standonck, Jean (l. CXXVIv, i.e. CXXXv)

Somville, Jacques de (composed with Gaillard Ruzé and Philippe Bourgoing) (l. CXXXIr, i.e. CXXXVr)

[Amboise, Georges d'] Ad legatum (l. CXXXIIIr, i.e. CXXXVII)

[Amboise, Pierre d'?] Ad legatum Galliarum (l. CXXXIIIIr, i.e. CXXXVIII)

Ad senatores Burdegaliae (to the senators of Bordeaux) (l. CXXXVIr, i.e. CXLr)

Ad pauperes Minti Acuti (to the pupils of the collège de Montaigu) (l. CXXXVIII, i.e. CXLII)

Brant, Sebastian to Utenheim, Christoph von. Basel, June 3, 1498 (l. CLIIIr., i.e. CLVIIr)

Jean Raulin, a native of Toul, studied theology under Martinus de Magistris at the University of Paris and graduated there in 1479. Two years later he became grand-master of the Collège de Navarre. He was considered one of the most prominent exponents of the Nominalist school and a skilled popular preacher convinced of the necessity of a reform of the church. In 1497 he entered the Benedictine monastery of Cluny, a step he explains in a letter (ll. XLVIv-XLIv) to Christoph von Utenheim, then guardian of the Franciscans of Basel and later rector of the university and bishop. He worked for reform, not without the resistance of the local clergy, also in southern France, but especially in the monasteries of Saint-Martin-des-Champs and Saint-Germain-des-Prés until his death (cf. A. Renaudet, Préréforme et humanisme à Paris pendant les premières guerres d'Italie (1494-1517), Paris, 1916, pp. 165-170 and 234-236).

“Raulin apparait comme un exemple intéressant des grandeurs et limites des réformateurs de la fin du quinzième siècle. Ardent et ingénieux prédicateur, infatigable dénonciateur des vices des évêques et des moines, il est tributaire des représentations eschatologiques de son temps, qu'il developpe longuement. Pourtant on trouve, dans son oeuvre, parfois implicitement, les éléments dont se servira la Réforme catholique” (G.T. Badouelle, op. cit, p. 156).

[9108]