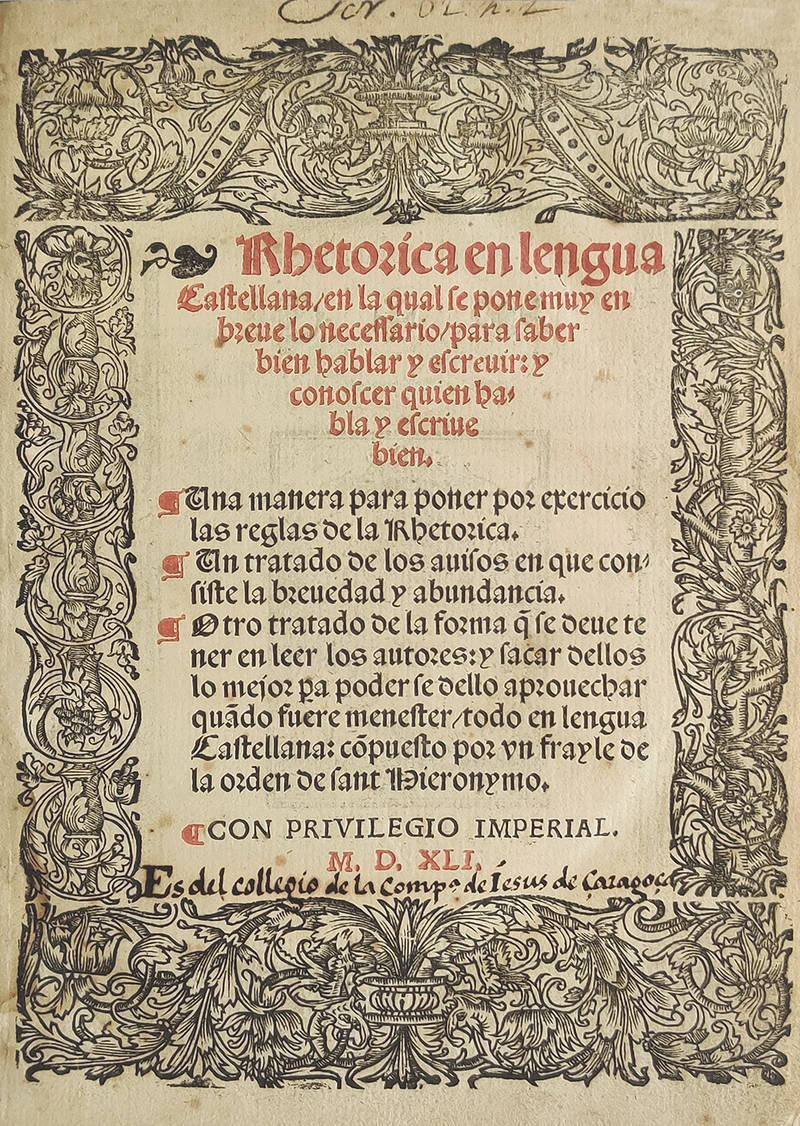

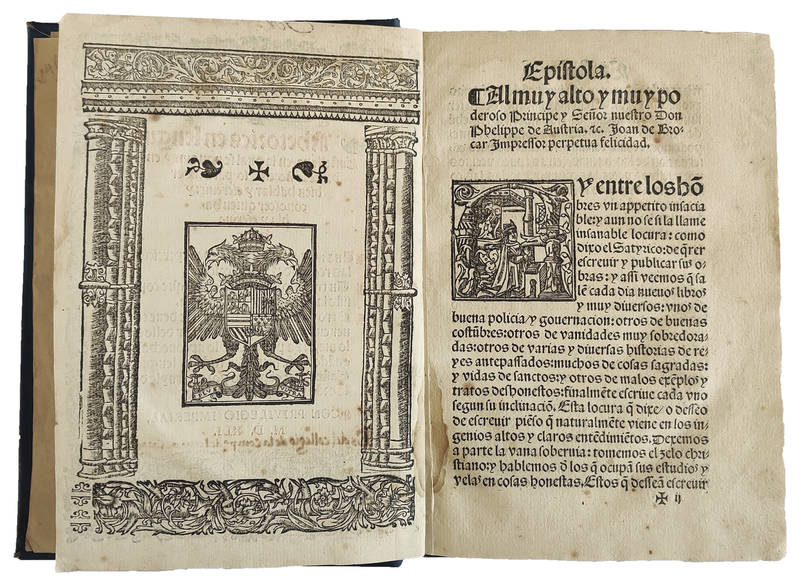

Rhetorica en lengua Castellana / en la qual se pone muy en breue lo necessario / para saber bien hablar y escreuir: y conoscer quien habla y escriue bien. Una manera para poner por exercicio las reglas de la Rhetorica. Un tratado de los auisos en que consiste la breuedad y abundancia. Otro tratado de la forma q[ue] se deue tener en leer los autores: y sacar dellos lo mejor p[ar]a poder se dello aprouechar qua[n]do fuere menester / todo en lengua Castellana: compuesto por un frayle de la orden de Sant Hieronymo. M.D.XLI.

Autore: SALINAS, Miguel de (O.S.H., ca. 1490-1567 or 1577)

Tipografo: Juan de Brocar

Dati tipografici: Alcalá de Henares, February 1541