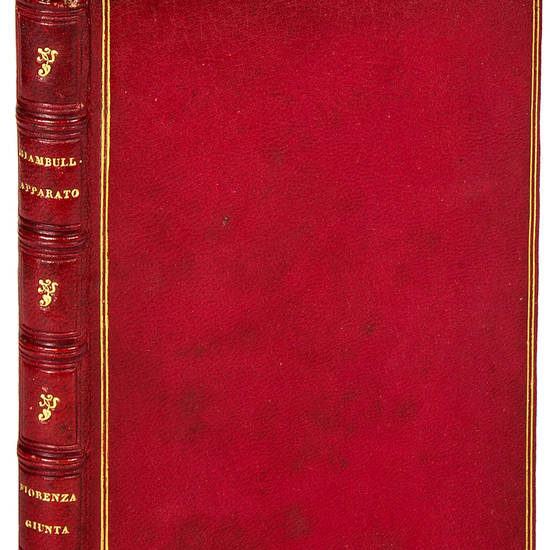

Apparato et feste nelle noze dello illustrissimo Signor Duca di Firenze, et della Duchessa sua Consorte, con le sue stanze, madriali, comedia, et intermedij, in quelle recitati

Autore: GIAMBULLARI, Pier Francesco (1495-1555)-LANDI, Antonio (1506-1569)

Tipografo: Benedetto Giunta

Dati tipografici: Firenze, 29 August 1539

“THIS IS ONE OF THE MOST INFORMATIVE OFFICIAL ACCOUNTS OF A FESTIVAL PUBLISHED DURING THE FIRST HALF OF THE CENTURY” (MITCHELL)

8vo (152x91 mm). 171, [3] pp. Collation: A-L8. Lacking leaf L7, a blank. Giunta's device on verso of l. L8. Late 19th-century red morocco, panels within double gilt fillet, gilt spine, dentelles, marbled endleaves (Legatoria T. Laengner, Milano). From the library of Pietro Ginori-Conti (his bookplate on the front pastedown) and Giannalisa Feltrinelli (see the sale catalogue of her library, Christie's 1998, no. 1205). Restorations to the outer borders of the last leaf. A nice copy.

Rare first edition of one the earliest wedding festival reports ever printed, apparently preceded only by the Ordine delle nozze di Costanzo Sforza, signore di Pesaro, et Camilla de Aragonia, sua consorte (Vicenza, 1475). Written in the form of a letter to Giovanni Bandini, orator of the Duke of Florence at the Emperor's court, the book describes the festivities, apparatuses, and shows organized to celebrate, in the Summer of 1539, the wedding of Cosimo I de' Medici and Eleonora de Toledo, daughter of the Viceroy of Naples Pietro de Toledo.

The account includes the full text of Il Commodo, a comedy by Antonio Landi staged on July 9th in the courtyard of the Medici Palace in Via Larga, as well as the Intermedi by Giambattista Strozzi. The comedy's main character, Doctor Ricciardo, is “an irascible bigot who makes life miserable for all his family. There were five intermezzi […] all carefully preserved in the printed text, which must have diverted the noble company” (M.T. Herrick, Italian Comedy in the Renaissance, Urbana-London, 1966, p. 62). The stage, designed by Aristotele da Sangallo (1481-1551), is considered “a watershed in the evolution of a court theatre of a type which conquered Europe” (R. Strong, Art and Power. Renaissance Festivals 1450-1650, Berkeley-Los Angeles, 1984, p. 34).

“Duke Cosimo I de' Medici and Eleonora of Toledo's marriage in June 1539 and the nuptial celebrations were of political and cultural significance to the Medici dukedom. The immediate political implication of the marriage is apparent. Eleonora was a daughter of Don Pedro de Toledo, the Viceroy of Naples and one of the most powerful noblemen in the Spanish world. The marriage strengthened Cosimo's allegiance to Emperor Charles V, whose soldiers still controlled the fortress of Florence. The marriage also offered an unmistakable opportunity for Cosimo to establish his as yet unstable visual imagery as the ruler. Like other public events of the Italian Renaissance princes, the marriage celebrations were a highly orchestrated affair, rich in allegorical representations […] The decorative projects for the nuptials, from Eleonora's procession at the gate of Florence to the banquet at the Palazzo Medici, transported the entire city to an alternate reality. They literally and symbolically linked space and time. Their allegorical references ranged from allusions grounded in classical mythology and ancient Roman history to immediate Medici ancestors, just as they also looked ahead to the future. The journey of Eleonora of Toledo began on June 11, 1539, the twentieth birthday of Duke Cosimo, when she left Naples with seven galleys. She arrived at Livorno and met Cosimo en route to Pisa. The couple then went to Poggio a Caiano, the Medici country house that had been built by Lorenzo Il Magnifico, on June 25. On June 29 Eleonora finally made her elaborate entry into Florence, processing slowly through the city while Cosimo took a shorter route to the Palazzo Medici in order to receive the bride formally. The procession began at the Porta al Prato, one of the western gates of the city. Having proceeded along the Arno, Eleonora paid a visit to the city's main cathedral, Santa Maria del Fiore, and turned up to the Piazza San Marco before she arrived at the Palazzo Medici. There a luxurious wedding banquet was held and a comedy was performed […] Cosimo was minutely involved in the planning of the marriage, set to capitalize on the propagandistic potential the occasion offered. He even decided upon the number of bridesmaids and how Eleonora and his mother should greet each other. Nonetheless, the marriage celebrations were a highly collaborative affair that brought together the works of a new generation of artists, musicians and writers, whose participation was desperately needed because of the emigration of the Florentine talents after the siege of Florence in 1530. Many indeed emerged visibly in the cultural and artistic life of Florence under Duke Cosimo. Giambattista Gelli, the writer of stanzas performed at the banquet, and Antonio Landi, the author of the comedy, as well as Giambullari, became eminent members of the Accademia Fiorentina, an institution dedicated to the study of the Tuscan vernacular and thus aimed at propagation of Florentine cultural eminence. Among the young artists who participated in the decorations was Agnolo Bronzino, one the most prominent painters in Duke Cosimo's service in the years to come. It is easy to assume that the emergence of a new cultural community worked to Cosimo's advantage where he was able to select and control its members. The marriage festivities in 1539 thus may appear a perfect example of Cosimo's absolute control over the Florentine cultural community […] I have discussed how the decorative program and festivities for Duke Cosimo's wedding figured him as a competent and independent ruler by celebrating his father, Giovanni delle Bande Nere, in imperial trappings and how his regime was also consciously projected as a continuation, if not fulfilment, of republican aspirations. In the light of these arguments, it is possible to envision that the decorative program and thematic occupations of the festivities for Cosimo's wedding in 1539 essentially created a genealogy in two dimensions. On the one hand, Giovanni, never before celebrated publicly as one of the Medici illustri, was figured alongside the illustrious Medici ancestors like Cosimo Il Vecchio and Lorenzo Il Magnifico that Cosimo was destined to follow. On the other hand, his regime was put in the context of the entire history of Florence as a rightful heir to the city's glorious republican past” (S. Woo Kim, Historiography of Duke Cosimo I de' Medici's Cultural Politics and Theories of Cultural Hegemony and Opposition, in: “Michigan Journal of History”, inverno 2006, pp. 11-12 e 26).

Edit 16, CNCE20908; Adams, G-584; D. Decia–R. Delfiol–L.S. Camerini, I Giunti tipografi editori di Firenze (1497-1570). Parte prima, Florence, 1978, no. 235; D. Moreni, Bibliografia storico-ragionata della Toscana, Florence, 1805, I, p. 427; Gamba, 2750; Catalogue de livres anciens et modernes… composant la bibliothèque de feu M. D.-E.-F. Ruggieri, Paris, 1885, no. 286; Clubb, 535; B. Mitchell, Italian civic Pageantry in the High Renaissance, Florence, 1979, pp. 51-52; C. Valacca, La vita e le opere di Messer Pierfrancesco Giambullari, prima parte 1495-1541, Bitonto, 1898, pp. 41-46; A.C. Minor & B. Mitchell, eds., A Renaissance Entertainment. Festivities for the Marriage of Cosimo I, Duke of Florence, in 1539, Columbia, 1968, passim.

[6941]