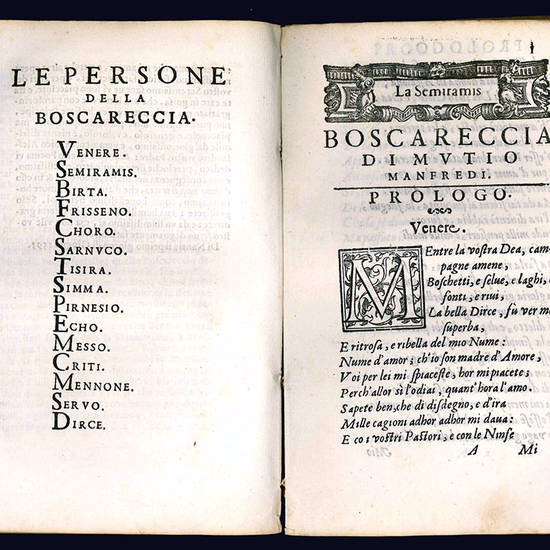

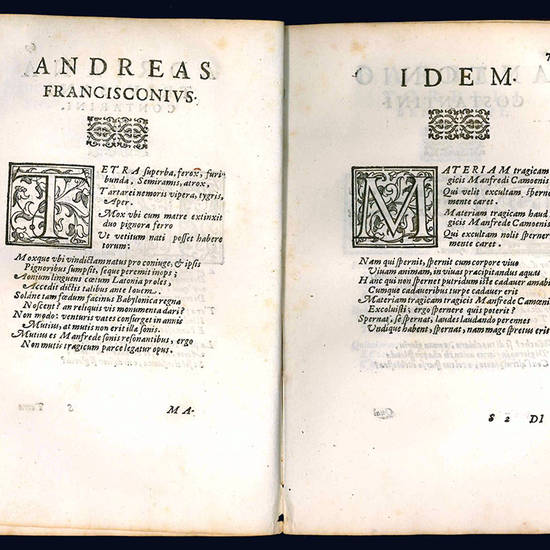

Two works in one volume, 4to (187x136 mm). [4], 92; [4], 67, [3: errata] leaves (the last is a blank). Collation: a4 A-Z4; a4 A-R4 [χ]2. With the printer's device on both title pages. In addition to the above-mentioned errata, in our copy has been loosely inserted a double-leaf of additional errata to both works, which is not called for in any bibliography. Contemporary vellum, inked title along the spine and on front panel (lacking ties, spine partly opened). Some light browning and foxing, a fine copy.

I. First edition of this tragedy in five acts written in free hendecasyllabic verses with a dedication to Cardinal Odoardo Farnese dated from Nancy, May 1, 1593. ''The climax of the Italian tragedy of blood may be illustrated by Muzio Manfredi's Semiramis [...] The plot was based on the semi-mythical history of the fabulous warrior-queen who succeeded her husband Ninus as ruler of Assyria and founded the city of Babylon. The scene is Babylon at the close of Semiramis' career. Ninus has been dead for some time, and their only son is now grown. Manfredi's principal model was Cinthio's Orbecche, but he also borrowed from Speroni's Canace and probably from Groto's Dalida'' (M.T. Herrick, Italian Tragedy in the Renaissance, Urbana, IL, 1965, pp. 206-207).

Manfredi composed his tragedy on the Assyrian queen around 1583. Curiously during the same period the young Spanish dramatist, Cristàbal de Virués (1550-1614), who then resided in Italy, wrote a drama on the same subject, La gran Semiramis (cf. A. Giordano Gramegna, II sentimento tragico nella ''Semiramis'' di Muzio Manfredi e nella ''Gran Semiramis'' di Cristàbal de Virués. Tecnica teatrale, in: ''Nascita della tragedia di poesia nei paesi europei'', Rome, 1990, pp. 301-321).

At the end of the work are printed several laudatory verses addressed to the author. Among them are compositions by Adriana Trivisani Contarini, Barbara Torelli Benedetti, Bernardino Baldi, Bernardino Baldini, Camillo Camili, Giuliano Goselini, Guidobaldo Bonarelli della Rovere, Orazio Ariosto, Maddalena Campiglia, Stefano Guazzo, Torquato Tasso, Veronica Franco and many others (cf. M. Manfredi & A. Decio, La Semiramis. Acripanda. Due regine del teatro rinascimentale, G. Distaso, ed., Taranto, 2002, passim).

II. First edition of this dramatized version of the love story between Semiramis and the Assyrian general Onnes. Each act of this pastoral is accompanied by a chorus and at the end is found a dance in homage to Hymenaeus. In the dedication (dated Nancy, June 1, 1593) to Duke Ranuccio Farnese Manfredi states that he had sent a manuscript copy of his 'favola' to a Milanese nobleman, who asked for it. Although he was disposed to stage the drama in Milan, Manfredi had no response and decided to dedicate it to Ranuccio, brother of Odoardo to whom he had alredy dedicated his tragedy.

Muzio Manfredi, a nobleman born in Cesena, after a short stay at the Roman court, moved around 1580 to Parma, where he entered the service of the Farnese family. As a member of the Accademia degli Innominati, he knew the playwrights Pomponio Torelli and Giovan Battista Guarini. In Parma he published an important edition of Tasso's Gerusalemme liberata (1581). In 1584 he found a patron in the person of Ferrante II Gonzaga at Guastalla, and in 1591 became secretary to the Duchess Dorothea of Lorraine, first at Tortona (where he got married with Ippolita Benigni, one of the Duchess' court ladies), and later at Nancy (cf. M.E. Briard, Le poète Muzio Manfredi et Dorothea de Lorraine, duchesse de Brunswick, in: “Journal de la Société d'archéologie lorraine”, XXXVIII, 1889, pp. 29-35). “Intrapresa una brillante carriera di poeta cortigiano e galante animatore di salotti, che lo vede protagonista nelle Corti romana, parmense e guastallese, il poeta giunge ai vertici della sua fortuna di artista e ‘gentiluomo' intorno alla metà degli anni '80. Ma dopo quella data, una serie di vicissitudini e di gravi incidenti con la classe signorile che fino ad allora lo aveva sostenuto e gratificato, lo porterà, fra momenti travagliati e dolorosi, ad una vecchiaia di emarginazione e di miseria” (L. Denarosi, Il principe e il letterato: due carteggi inediti di Muzio Manfredi, in: “Studi italiani”, 1997, 9, no. 1, p. 153). His bitter diatribe against the Duke of Mantua, Vincenzo Gonzaga, contained in the dedication of the Semiramis boschereccia, costed him the latter's favour, which Manfredi tried in vain to regain after his return from France. He spent his last years in extreme poverty plying between Pavia, Ravenna, and Rome (cf. M.A. Bertolotti, Muzio Manfredi e Passi Giuseppe letterati in relazione col duca di Mantova, in: “Il Buonarroti”, Roma, 1888, III, p. 119 ff.). Manfredi was a prolific writer and a member of various important academies (Accademia dei Confusi in Bologna, Accademia degli Invaghiti in Ferrara, and Accademia Olimpica in Vicenza). His numerous madrigals (1587) were very popular among contemporary musicians, who set many of them to music. Among his others publications, are poems (Rime, 1575), a work called Sogno amoroso (1596), the poetic garland Cento donne cantate (1580), and the collection Lettere brevissime (1606), in which he discusses topics related to tragedy.

Edit16, CNCE 38297 and CNCE 49300; M. Bregoli Russo, Renaissance Italian Theater, Firenze, 1984, no. 387 (I); L.G. Clubb, Italian Plays in the Folger Library, Florence, 1968, no. 584 (II); Biblioteca Nazionale Braidense, Le edizioni del XVI secolo, I-Edizioni lombarde, Milan, 1981, nos. 40-41.

[86]

![La Semiramis tragedia di Mutio Manfredi il Fermo, Academico Innominato, Invaghito et Olimpico. [Legato con/bound with:] La Semiramis boscareccia di Mutio Manfredi. La Semiramis tragedia di Mutio Manfredi il Fermo, Academico Innominato, Invaghito et Olimpico. [Legato con/bound with:] La Semiramis boscareccia di Mutio Manfredi.](https://www.libreriagovi.com/typo3temp/pics/ceec1c9b78.jpg)

![La Semiramis tragedia di Mutio Manfredi il Fermo, Academico Innominato, Invaghito et Olimpico. [Legato con/bound with:] La Semiramis boscareccia di Mutio Manfredi. La Semiramis tragedia di Mutio Manfredi il Fermo, Academico Innominato, Invaghito et Olimpico. [Legato con/bound with:] La Semiramis boscareccia di Mutio Manfredi.](https://www.libreriagovi.com/typo3temp/pics/88cf73529b.jpg)

![La Semiramis tragedia di Mutio Manfredi il Fermo, Academico Innominato, Invaghito et Olimpico. [Legato con/bound with:] La Semiramis boscareccia di Mutio Manfredi. La Semiramis tragedia di Mutio Manfredi il Fermo, Academico Innominato, Invaghito et Olimpico. [Legato con/bound with:] La Semiramis boscareccia di Mutio Manfredi.](https://www.libreriagovi.com/typo3temp/pics/525ea3cdef.jpg)

![La Semiramis tragedia di Mutio Manfredi il Fermo, Academico Innominato, Invaghito et Olimpico. [Legato con/bound with:] La Semiramis boscareccia di Mutio Manfredi. La Semiramis tragedia di Mutio Manfredi il Fermo, Academico Innominato, Invaghito et Olimpico. [Legato con/bound with:] La Semiramis boscareccia di Mutio Manfredi.](https://www.libreriagovi.com/typo3temp/pics/0d35194dd6.jpg)

![La Semiramis tragedia di Mutio Manfredi il Fermo, Academico Innominato, Invaghito et Olimpico. [Legato con/bound with:] La Semiramis boscareccia di Mutio Manfredi. La Semiramis tragedia di Mutio Manfredi il Fermo, Academico Innominato, Invaghito et Olimpico. [Legato con/bound with:] La Semiramis boscareccia di Mutio Manfredi.](https://www.libreriagovi.com/typo3temp/pics/e8e9d0e2c5.jpg)